Systematics and the Exploration of Life

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Systematics and the Exploration of Life» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Systematics and the Exploration of Life

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Systematics and the Exploration of Life: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Systematics and the Exploration of Life»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Systematics and the Exploration of Life — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Systematics and the Exploration of Life», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

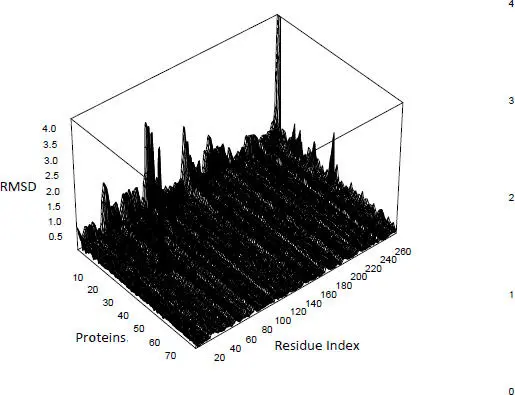

Figure 2.7. RMSD calculated for 78 mutants of a transferase, the reference being that of Pyrococcus horikoshii (PDB code 2dek chain A). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/grandcolas/systematics.zip

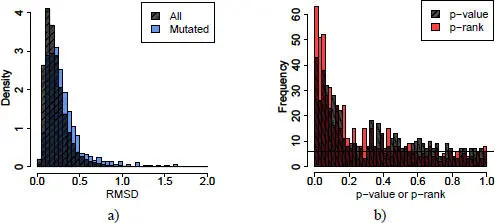

Figure 2.8. Distribution of RMSD, p-values and p-ranks. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/grandcolas/systematics.zip

COMMENT ON FIGURE 2.8. – a) Distribution of RMSDs for all positions (crosshatched) or mutated residues alone (blue) for 580 mutations distributed in 11 families. b) Distribution of empirical p-values (crosshatched) and p-ranks (red) of mutated residues. The black line represents the uniform distribution of p-values or p-rank, in other words, the distribution expected if 580 RMSDs are randomly drawn from the crosshatched distribution of (a).

In order to take into account the global variability due to variations in experimental conditions, the gross RMSD should not be used, but a transformation of it. Considering ranks instead of values is a robust transformation used in many statistical tests. The RMSDs in each profile are first ranked in ascending order, and then the ranks are divided by the number of RMSDs in the profile (in other words, the length of the chain). The result is dimensionless, stacked values that allow the characterization of each protein in the family. If the mutations had no particular effect on the RMSD, the distribution of these p-values should be uniform, which is not what is observed ( Figure 2.8(b)). This first transformation allows the experimental variability, but not the intrinsic flexibility of the molecule, to be taken into account. Indeed, in very flexible regions, seeing as the RMSD is large, the first ranking, and thus the empirical p-value, will also always be large. It is therefore necessary to make a second classification, that of the empirical p-value, for each position in each family. The new empirical p-value is then called the p-rank in order to differentiate it from the first one.

The place where the mutation takes place is the one most likely to be disturbed, at least in intensity (with a high RMSD value). Among all the calculated RMSDs, there are 580 positions corresponding to a mutation. Also, the p-rank distribution of RMSDs centered on mutated residues is not uniform ( Figure 2.8(b)). Among the top 5% of the largest RMSDs, 12% are mutation-centered; among the top 5% of empirical p-ranks, 15% are mutation-centered; and among the top 5% of p-ranks, 25% are mutation-centered. These two transformations thus allow better isolation of locally disrupted regions.

The RMSDs calculated in the least flexible regions, buried, or located in the alpha helices and beta sheets are small and have lower variability (0.21 Å ± 0.19, 0.22 Å ± 0.19, 0.19 Å ± 0.14, respectively) compared to all RMSDs (0.24 Å ± 0.25). Local disruptions of the main chain in these regions are thus more difficult to isolate, but as we take into account the flexibility of the proteins in our transformations, we can extract disruptions in these regions that, although small, are significant because the variability is low. For example, 17% of the residues are in beta strands in the whole sample. Among the segments with the largest 5% RMSD, the proportion of residues located in beta strands falls to 9%, while for the smallest 5% p-rank, it rises to 17%. We have thus effectively eliminated the bias due to the intrinsic rigidity of the beta sheets.

2.7. Conclusion

The methodology presented allows the identification of disturbed regions in protein structures by taking into account biases due to experimental variations and protein flexibility. Now that we know that mutations do indeed disrupt the main chain and that these disruptions are measurable with current techniques, it would be interesting to model them, especially to improve the predictions of ΔΔG, for which the carbon chain is rigid.

Two models exist for the accommodation of the main chain under the effect of amino acid substitution. The first (Davis et al . 2006) is derived from the observation of alternative atomic positions in ultra-high resolution crystallographic structures. It has been successfully used to improve Rosetta’s calculation of ΔΔG (Lauck et al . 2010). The second (Bordner and Abagyan 2004) was constructed from data collected on 2,141 pairs of protein structures, only differing by a single point mutation. This model also improved Gibbs’ prediction of free energy after a mutation. The selection method presented allows the identification of fragments where the main chain was more disrupted than expected. Using this database instead of the previous ones should improve the models.

2.8. References

Alberts, B., Bray, D., Lewis, J., Raff, M., Toberts, K., and Watson, J. (1994). Molecular Biology of the Cell . Garland Publishing, New York.

Anfinsen, C.B. (1973). Principles that govern the folding of protein chains. Science , 181, 223–230.

Berman, H.M., Westbrook, J., Feng, Z., Gilliland, G., Bhat, T.N., Weissig, H., Shindyalov, I.N., and Bourne, P.E. (2000). The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Research , 28, 235–242.

Bloom, J.D., Raval, A., and Wilke, C.O. (2007). Thermodynamics of neutral protein evolution [Online]. Genetics , 175, 255–266. Available: https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.106.061754.

Bordner, A.J. and Abagyan, R.A. (2004). Large-scale prediction of protein geometry and stability changes for arbitrary single point mutations [Online]. Proteins , 57, 400–413. Available: https://doi.org/10.1002/prot.20185.

Bressler, S. and Talmud, D. (1944). On the nature of globular proteins. Comptes rendus de l’Académie des sciences de l’URSS , 43, 310–314.

Davis, I.W., Arendall, W.B., Richardson, D.C., and Richardson, J.S. (2006). The backrub motion: How protein backbone shrugs when a sidechain dances [Online]. Structure , 14, 265–274. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.str.2005.10.007.

DePristo, M.A., Weinreich, D.M., and Hartl, D.L. (2005). Missense meanderings in sequence space: A biophysical view of protein evolution [Online]. Nature Reviews Genetics , 6, 678–687. Available: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg1672.

Dunbrack, R.L. (2002). Rotamer libraries in the 21st century [Online]. Current Opinion in Structural Biology , 12, 431–440. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-440X(02)00344-5.

Gong, S., Worth, C.L., Bickerton, G.R.J., Lee, S., Tanramluk, D., and Blundell, T.L. (2009). Structural and functional restraints in the evolution of protein families and superfamilies [Online]. Biochemical Society Transactions , 37, 727–733. Available: https://doi.org/10.1042/BST0370727.

Gromiha, M.M. and Sarai, A. (2010). Thermodynamic database for proteins: Features and applications [Online]. Methods in Molecular Biology , 609, 97–112. Available: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-60327-241-4_6.

Guerois, R., Nielsen, J.E., and Serrano, L. (2002). Predicting changes in the stability of proteins and protein complexes: A study of more than 1000 mutations [Online]. Journal of Molecular Biology , 320, 369–387. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00442-4.

Guo, H.H., Choe, J., and Loeb, L.A. (2004). Protein tolerance to random amino acid change [Online]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , 101, 9205–9210. Available: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0403255101.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Systematics and the Exploration of Life»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Systematics and the Exploration of Life» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Systematics and the Exploration of Life» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.