Systematics and the Exploration of Life

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Systematics and the Exploration of Life» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Systematics and the Exploration of Life

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Systematics and the Exploration of Life: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Systematics and the Exploration of Life»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Systematics and the Exploration of Life — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Systematics and the Exploration of Life», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Thompson’s main thesis is that “physical forces”, such as gravity or surface tension phenomena, play a preponderant role in the determinism of organic forms and their diversity within the living world. His structuralist conception of the diversity of forms is accompanied by a critique of the Darwinian theory of evolution, but this critique is in fact based on an erroneous interpretation of the causal context (efficient cause vs. formal cause) presiding over the emergence of forms (Medawar 1962; Gould 1971, 2002, p. 1207).

The notion of symmetry is present in the backdrop throughout the book. The successive chapters go through the different orders of magnitude of the organization of life and the physical forces that prevail at each of these scales. The skeletons of radiolarians, the spiral growth of mollusk shells and the diversity of phyllotactic modes are some of the examples illustrating the pivotal role of symmetry in the architecture of biological forms. This interest in symmetry is in line with the work of Ernst Haeckel, whose book Kunstformen der Natur (Haeckel 1899) offers bold anatomical representations emphasizing (and sometimes idealizing) the exuberance and sophistication of symmetry patterns found in nature. Thompson sees the harmony and regularity of symmetric forms as the geometric manifestation of the mathematical principles that establish a fundamental basis for his theory of forms.

This emphasis on geometry finds its clearest expression in the last and most famous chapter of the book, “On the theory of transformation, or the comparison of related forms” (Arthur 2006). Thompson proposes a method for comparing the forms between related taxa, based on the idea of (geometric) transformation from one form to another, by means of continuous deformations of varying degrees of complexity. The morphological differences (location and magnitude) are then graphically expressed by applying the same transformation to a Cartesian grid placed on the original form. In spite of his admiration for mathematics, Thompson’s approach nevertheless remains qualitative and without a formal mathematical framework for its empirical implementation. These graphical representations will, however, have a considerable conceptual impact on biologists working on the issues of shape and shape change. Several more or less elegant and operational attempts at quantitative implementation were made during the 20th century (see Medawar (1944), Sneath (1967) and Bookstein (1978), for example), up until the formulation of deformation grids using the thin-plate splines technique proposed by Bookstein (1989), which is still in use today.

Beyond the questions of symmetry, Thompson’s idea of combining geometry and biology to study shapes remains at the heart of the principles and methods of modern morphometrics (Bookstein 1991, 1996).

1.3. Isometries and symmetry groups

In this section, we propose an overview of the mathematical characterization of the notion of symmetry, as it can be applied to organic forms. The physical environment in which living organisms evolve is comparable to a three-dimensional Euclidean space. It is denoted by E 3. A geometric figure is said to be symmetric if there are one or more transformations which, when applied to the figure, leave it unchanged. Symmetry is thus a property of invariance to certain types of transformations. These transformations are called isometries .

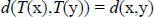

Formally, an isometry of the Euclidean space E 3is a transformation T : E 3→ E 3that preserves the Euclidean metric, that is, a transformation that preserves lengths (Coxeter 1969; Rees 2000):

for all x and y points belonging to E 3.

The different isometries of E 3are obtained by combining rotation and translation (x ↦ α R x + t , where R is an orthogonal matrix of order 3 and t is a vector of  ). They include the identity, translations, rotations around an axis, screw rotations (rotation around an axis + translation along the same axis), reflections with respect to a plane, glide reflections (reflection with respect to a plane + translation parallel to the same plane) and rotatory reflections (rotation around an axis + reflection with respect to a plane perpendicular to the axis of rotation). The set of isometries for which an object is invariant constitutes the symmetry group of the object.

). They include the identity, translations, rotations around an axis, screw rotations (rotation around an axis + translation along the same axis), reflections with respect to a plane, glide reflections (reflection with respect to a plane + translation parallel to the same plane) and rotatory reflections (rotation around an axis + reflection with respect to a plane perpendicular to the axis of rotation). The set of isometries for which an object is invariant constitutes the symmetry group of the object.

For biologists wishing to explore symmetry in an organism, the correct identification of the symmetry group is important because it conditions the relevance of the morphometric analysis to come. The symmetry group of the organic form is always a subgroup of the isometries of E 3. In particular, the translation has no exact equivalent in biology, since the physical extension of an organism is finite (the finite repetition of arthropod segments, for example). Translational symmetry is therefore approximate. The other isometries form a finite subgroup of Euclidean isometries, including the cyclic and dihedral groups, as well as the tetrahedral, octahedral and icosahedral groups of the Platonic solids that were dear to Thompson (1942, Chapter 9). It appears that, essentially, the symmetry patterns of biological shapes correspond to cyclic groups (rotational symmetry of order n alone [ Cn ], or combined with a plane of symmetry perpendicular to the axis of rotation [ Cnh ], or with n planes of symmetry passing through the axis of rotation [ Cnv ]). The bilateral symmetry of bilaterians corresponds, for example, to the group C1v , in other words, a rotation of 2π/1 (identity) combined with a reflection across a plane passing through the rotation axis.

1.4. Biological asymmetries

Another aspect of the imperfect nature of biological symmetry rests on the existence of deviations from the symmetric expectation (Ludwig 1932). These deviations manifest themselves to varying degrees and have distinct developmental causes. Let us consider the general case of a biological structure, whose symmetry emerges from the coherent spatial repetition of a finite number of units (e.g. the two wings of the drosophila, the five arms of the starfish). Different types of asymmetry are recognized (see also Graham et al . (1993) and Palmer (1996, 2004)):

– directional asymmetry corresponds to the case where one of the units tends to systematically differ from the others in terms of size or shape. A classic example is the narwhal, whose “horn” is in fact the enlarged canine tooth of the left maxilla, while the vestigial right canine tooth remains embedded in the gum;

– antisymmetry is comparable in magnitude to directional asymmetry, but the unit that differs from the others in size or shape is not the same from one individual to another. The claws of the fiddler crab show this type of asymmetry, the most developed claw being the right or the left, depending on the individual;

– fluctuating asymmetry is an asymmetry of very small magnitude and is therefore much more difficult to detect. It is the result of random inaccuracies in the developmental processes during the formation of the units that compose the biological structure. Fluctuating asymmetry is a priori always present, even if it is not always measurable. Its magnitude is considered a measure of developmental precision and has often been used (albeit sometimes controversially) as a marker of stress.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Systematics and the Exploration of Life»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Systematics and the Exploration of Life» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Systematics and the Exploration of Life» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.