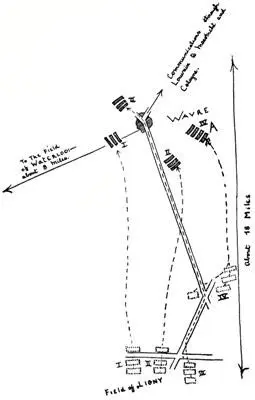

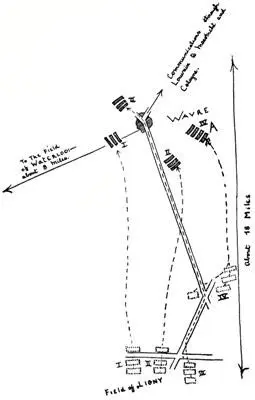

The Second Corps followed the First, and ended its march on the southern side of Wavre, round about the village of St. Anne.

The Third Corps did not complete the retreat until the end of daylight upon the 17th, and then marched through Wavre, across the river to the north, and bivouacked around La Bavette.

Finally, still later on the same evening, the Fourth Corps, that of Bulow, which had come to Ligny too late for the action, marching by the eastward lanes, through Sart and Corry, lay round Dion Le Mont.

By nightfall, therefore, on Saturday the 17th of June, we have the mass of the Prussian army safe round Wavre, and duly disposed all round that town in perfect order.

With the exception of a rearguard, which did not come up until the morning of the Sunday, all had been safely withdrawn in the twenty-four hours that followed the defeat at Ligny.

It may be asked why this great movement had been permitted to take place without molestation from the victors.

Napoleon would naturally, of course, after his defeat of the Prussians, withdraw to the west the greater part of the forces he had used against Blucher at Ligny and direct them towards the Brussels road in order to use them next against Wellington. But Napoleon had left behind him Grouchy in supreme command over a great body of troops, some 33,000 in all, whose business it was to follow up the Prussians, to find out what road they had taken; at the least to watch their movements, and at the best to cut off any isolated bodies or to give battle to any disjointed parts which the retreat might have separated from support. In general, Grouchy was to see to it that the Prussians did not return.

In this task Grouchy failed. True, he was not given his final instructions by the Emperor until nearly midday of the 17th, but a man up to his work would have discovered the line of the Prussian retreat and have hung on to it. Grouchy failed, partly because he was insufficiently provided with cavalry, partly because he was a man excellent only in a sudden tactical dilemma, incompetent in large strategical problems, partly because he mistrusted his subordinates, and they him; but most of all because of an original prepossession (under which, it is but fair to him to add, all the French leaders lay) that the Prussian retreat had taken the form of a flight towards Namur, along the eastern line of communications, while, as a fact, it had taken the form of a disciplined retreat upon Wavre and the north.

At ten o’clock in the evening of Saturday the 17th, twenty-four hours after the battle of Ligny, and at the moment when the whole body of the Prussian forces was already reunited in an orderly circle round Wavre, Grouchy, twelve miles to the south of them, was beginning—but only beginning—to discover the truth. He wrote at that hour to the Emperor that “the Prussians had retired in several directions,” one body towards Namur, another with Blucher the Commander-in-chief towards Liège, and a third body apparently towards Wavre . He even added that he was going to find out whether it might not be the larger of the three bodies which had gone towards Wavre, and he appreciated that whoever had gone towards Wavre intended keeping in touch with the rest of the Allies under Wellington. But all that Grouchy did after writing this letter proves how little he, as yet, really believed that any great body of the enemy had marched on Wavre. He anxiously sent out, not northward, but eastward and north-eastward, to feel for what he believed to be the main body of the retreating foe.

During the night he did become finally convinced by the mass of evidence brought in by his scouts that round Wavre was the whole Prussian force, and the conclusion that he came to was singular! He took it for granted that through Wavre the Prussians certainly intended a full retreat on Brussels. He wrote at daybreak of the 18th of June that he was about to pursue them.

That Blucher could dream of taking a short cut westward, thus effecting an immediate junction with Wellington, never entered Grouchy’s head. He did not put his army in motion until after having written this letter. He advanced his troops in a decent and leisurely manner up the Wavre road through the mid hours of the day, and himself, just before noon, wrote a dispatch to the Emperor; he wrote it from Sart, a point ten miles south of Wavre. In that letter he announced “his intention to be massed at Wavre that night ,” and begging for “orders as to how he should begin his attack of the next day .”

The next day! Monday!

Already, hours before—by midnight of Saturday—Blucher had sent his message to Wellington assuring him that the Prussians would come to his assistance upon Sunday, the morrow.

Even as Grouchy was writing, the Prussian Corps were streaming westward across country to appear upon Napoleon’s flank four hours later and decide the campaign.

Having written his letter, Grouchy sat down to lunch. As he sat there at meat, far off, the first shots of the battle of Waterloo were fired.

* * * * *

So far, we have followed the retreat of the Prussians northwards from their defeat at Ligny. With the exception of the rearguard, they were all disposed by the evening of Saturday the 17th in an orderly fashion round the little town of Wavre. We have also followed the methodical but tardy and ill-conceived pursuit in which Grouchy felt out with his cavalry to discover the line of the Prussian retreat, and continued to be in doubt of its nature at least until midnight, and probably until even later than midnight, in that night between Saturday the 17th, evening, and Sunday the 18th of June.

We have further seen that during the morning of Sunday the 18th of June he was taking no dispositions for a rapid pursuit, but, being now convinced that the Prussians merely intended a general retreat upon Brussels, proposed to follow them in order to watch that retreat, and, if possible, to shepherd them eastwards. He wrote, as we have just said, to the Emperor in the course of that morning of the Sunday, announcing that he meant to mass his troops at Wavre by nightfall, and asking for orders for the next day.

What the Prussians were doing during that Sunday morning when Grouchy was so quietly and soberly taking for granted that they could not or would not rejoin Wellington, and was so quietly shielding his own responsibility behind the Emperor’s orders, we shall see when we come to talk of the action itself—the battle of Waterloo.

Meanwhile we must return to the second half of the great strategic move, and watch the retreat of the Duke of Wellington during that same Saturday, and the stand which he made on the ridge called “the Mont St. Jean” by the nightfall of that day, in order to accept battle on the Sunday morning.

An observer watching the whole business of that Saturday from some height in the air above the valley of the Sambre, and looking northwards, would have seen on the landscape below, to his right, the Prussians streaming in great parallel columns upon Wavre from the battlefield of Ligny. He would have seen, scattered upon the roads, small groups of mounted men, here in touch with the last files of a Prussian column, there lost and wandering forward into empty spaces where no soldiers were. These were the cavalry scouts of Grouchy. South of these, and far behind the Prussian rear, separated from them by a gap of ten miles, a dense body of infantry, drawn up in heavy columns of route, was the corps commanded by Grouchy.

What would such an observer have seen upon the landscape below and before him to his left? He would have seen an interminable line of men streaming northward also, all afternoon, up the Brussels road from Quatre Bras; and behind them, treading upon their heels, another column, miles in length, pressing the pursuit. The retreating column, as it hurried off, he would see screened on its rear by a mass of cavalry, that from time to time charged and checked the pursuers, and sometimes put guns in line to hold them back. The pursuers, after each such check, would still press on. The first, the thousands in retreat, were Wellington’s command retiring from Quatre Bras; the second, the pursuers, were a body some 74,000 strong formed by the junction of Ney and Napoleon, and pressing forward to bring Wellington to battle.

Читать дальше