* * * * *

At Quatre Bras, Wellington had not been able, as he had hoped, to join the Prussians and save them from defeat. The French, under Ney, had held him up. He would even have suffered a reverse had Ney attacked promptly and strongly earlier in the day of Friday the 16th, but Ney had not acted promptly and strongly.

All day long reinforcements had come in one after the other, much later than the Duke intended, but in a sufficient measure to meet the tardy and too cautious development of Ney’s attack. Finally, the real peril under which the Duke lay (though he did not know it)—the junction of Erlon and his forces with Ney—had not taken place until darkness fell, and Erlon’s 20,000 had been wasted in the futile fashion which has been described and analysed.

The upshot, therefore, of the whole business at Quatre Bras was, that during the night between Friday and Saturday the 16th and the 17th the English and the French lay upon their positions, neither seriously incommoding the other.

During that night further reinforcements reached Wellington where his troops had bivouacked upon the positions they had held so well. Lord Uxbridge, in command of the British cavalry, and Ompteda’s brigade both came up with the morning, as did also Clinton’s division and Colville’s division, and so did the reserve artillery.

In spite of all these reinforcements, in spite even of the great mass of horse which Uxbridge had brought up, and of the new guns, Wellington’s position upon that morning of Saturday the 17th of June was, though he did not yet know it, very perilous.

He still believed that the Prussians were holding on to Ligny, and that they had kept their positions during the night, which night he had himself spent at Genappe, to the rear of the battlefield of Quatre Bras. 14

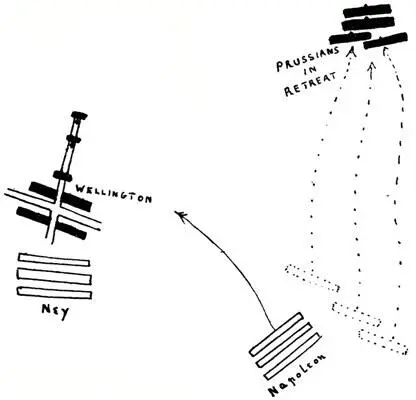

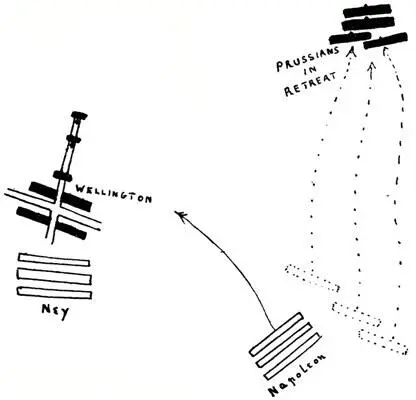

When Wellington awoke on the morning of Saturday in Genappe, there were rumours in the place that the Prussians had been defeated the day before at Ligny. The Duke went at once to Quatre Bras; sent Colonel Gordon off eastward with a detachment of the Tenth Hussars to find out what had happened, and that officer, finding the road from Ligny in the hands of the French, had the sense to scout up northwards, came upon the tail of the Prussian retreat, and returned to Wellington at Quatre Bras by half-past seven with the whole story: the Prussians had indeed been beaten; they were in full retreat; but a chance of retreat had lain open towards the north, and that was the road they had taken.

Wellington knew, therefore, before eight o’clock on that Saturday morning, that his whole left or eastern flank was exposed, and it was common-sense to expect that Napoleon, with the main body of the French, having defeated the Prussians at Ligny, would now march against himself, come up upon that exposed flank (while Ney held the front), and so outnumber the Anglo-Dutch under the Duke’s command. At the worst that command would be destroyed; at the best it could only hope, if it gave time for Napoleon to come up, to have to retreat westward, and to lose touch, for good, with the Prussians.

In such a plight it was Wellington’s business to retreat towards the north, so as to remain in touch with his Prussian allies, while yet that line of retreat was open to him, and before Napoleon should have forced a battle.

Sketch showing the situation in which Wellington was

at Quatre Bras on the morning of the 17th.

The Duke was in no hurry to undertake this movement, for as yet there was no sign of Napoleon’s arrival. The men breakfasted, and it was not until ten o’clock that the retreat began. He sent word back up the road to stop the reinforcements that were still upon their way to join him at Quatre Bras, and to turn them round again up the Brussels road, the way they had come, until they should reach the ridge of the Mont St. Jean, just in front of the village of Waterloo, where he had determined to stand. This done, he made his dispositions for retirement, and a little after ten o’clock the retreat upon Waterloo began. His English infantry led the retreat, the Netherland troops following, then the Brunswickers, and the last files of that whole great body of men were marching up the Brussels road northward before noon. Meanwhile, Lord Uxbridge, with his very considerable force of cavalry and the guns necessary to support it, deployed to cover the retreat, and watched the enemy.

That enemy was motionless. Ney did not propose to attack until Napoleon should come up. Napoleon and his troops, arriving from the battlefield of Ligny, were not visible until within the neighbourhood of two o’clock. As he came near the Emperor was perceived, his memorable form distinguished in the midst of a small escorting body, urging the march; and the English guns, during one of those rare moments in which war discovers something of drama, fired upon the man who was the incarnation of all that furious generation of arms. In a military study, this moment, valuable to civilian history, may be neglected.

The flood of French troops arriving made it hard for Uxbridge, in spite of his very numerous cavalry and supporting guns, to cover Wellington’s retreat.

The task was, however, not only successfully but nobly accomplished. Just as the French came up the sky had darkened and a furious storm had broken from the north-west upon the opposing forces. It was in the midst of a rain so violent that friend could be hardly distinguished from foe at thirty yards distance that the pursuit began, and to the noise of limbers galloped furiously to avoid capture, and of all those squadrons pursuing and pursued, was joined an incessant thunder.

Things are accomplished in war which do not fit into the framework of its largest stories, and tend, therefore, to be lost. Overshadowed by the great story of Waterloo, the work which Lord Uxbridge and his Horse did on that afternoon of Saturday the 17th of June is too often forgotten.

The ability and the energy displayed were equal.

The first deployment to meet the French advance, the watching of the retirement of Wellington’s main body, the continual appreciation of ground during a rapid and dangerous movement and in the worst of weather, the choice of occasional artillery positions—all these showed mastery, and secured the complete order of Wellington’s retreat. 15

The pursuit was checked at its most important point (where the French had to cross the river Dyle at Genappe) by a rapid deployment of the cavalry upon the slope beyond the stream, a rapid unlimbering of the batteries in retreat, and a double charge, first of the Seventh Hussars, next of the First Life Guards.

These charges were successful, they checked the French, and during the remainder of the afternoon the pursuit to the north of the Dyle slackened off until, before darkness, it ceased altogether.

Indeed, there was by that time no further use in it. The mass of Wellington’s army had reached, and had deployed upon, that ridge of the Mont St. Jean where he intended to turn and give battle. They were in a position to receive any immediate attack, and the purposes of mere pursuit were at an end.

Facing that ridge of the Mont St. Jean, where, at the end of the afternoon and through the evening, Wellington’s troops were already taking up their positions, was another ridge, best remembered by the name of a farm upon its crest, the “Belle Alliance.” This ridge formed the natural halting-place of the pursuers. From the height above Genappe to the ridge of the Belle Alliance was but 5000 yards; and if a further reason be quoted for the cessation of the pursuit and the ranging into battle array of either force, the weather will provide that reason.

Читать дальше