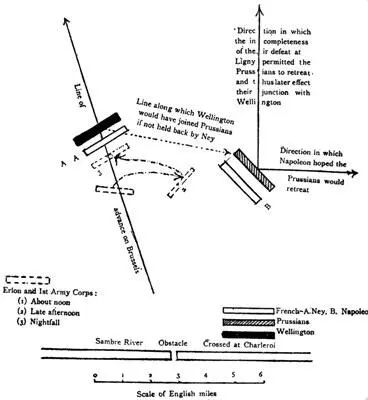

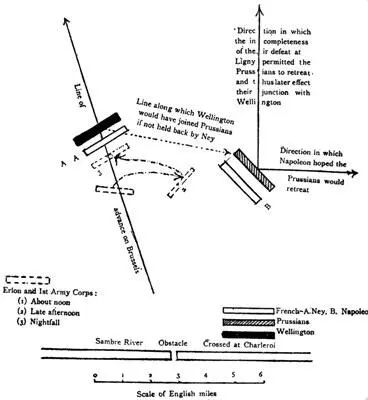

Such are the facts, and they explain all that followed (see Map, next page).

But it has rightly proved of considerable interest to historians to attempt to discover the human motives and the personal accidents of temperament and misunderstanding which led to so extraordinary a blunder as the utter waste of a whole army corps during a whole day, within an area not five miles by four.

It is for the purpose of considering these human motives and personal accidents that I offer these pages; for if we can comprehend Erlon’s error, we shall fill the only remaining historical gap in the story of Waterloo, and determine the true causes of that action’s result.

There are two ways of appreciating historical evidence. The first is the lawyer’s way: to establish the pieces of evidence as a series of disconnected units, to docket them, and then to see that they are mechanically pieced together; admitting, the while, only such evidence as would pass the strict and fossil rules of our particular procedure in the courts. This way, as might be inferred from its forensic origin, is particularly adapted to arriving at a foregone conclusion. It is useless or worse in an attempt to establish a doubtful truth.

The second way is that by which we continually judge all real evidence upon matters that are of importance to us in our ordinary lives: the way in which we invest money, defend our reputation, and judge of personal risk or personal advantage in every grave case.

This fashion consists in admitting every kind of evidence, first hand, second hand, third hand, documentary, verbal, traditional, and judging the general effect of the whole, not according to set legal categories, but according to our general experience of life, and in particular of human psychology. We chiefly depend upon the way in which we know that men conduct themselves under the influence of such and such emotions, of the kind of truth and untruth which we know they will tell; and to this we add a consideration of physical circumstance, of the laws of nature, and hence of the degrees of probability attaching to the events which all this mass of evidence relates.

It is only by this second method, which is the method of common-sense, that anything can be made of a doubtful historical point. The legal method would make of history what it makes of justice. Which God forbid!

Historical points are doubtful precisely because there is conflict of evidence; and conflict of evidence is only properly resolved by a consideration of the psychology of witnesses, coupled with a consideration of the physical circumstances which limited the matter of their testimony.

Judged by these standards, the fatal march and countermarch of Erlon become plain enough.

His failure to help either Ney or Napoleon was not treason, simply because the man was not a traitor. It proceeded solely from obedience to orders; but these orders were fatal because Ney made an error of judgment both as to the real state of the double struggle—Quatre Bras, Ligny—and as to the time required for the countermarch. This I shall now show.

Briefly, then:—

Erlon, as he was leading his army corps up to help Ney, his immediate superior, turned it off the road before he reached Ney and led it away towards Napoleon.

Why did he do this?

It was because he had received, not indeed from his immediate superior, Ney himself, but through a command of Napoleon’s, which he knew to be addressed to Ney , the order to do so.

When Erlon had almost reached Napoleon he turned his army corps right about face and led it off back again towards Ney.

Why did he do that?

It was because he had received at that moment a further peremptory order from Ney, his direct superior, to act in this fashion .

Such is the simple and common-sense explanation of the motives under which this fatal move and countermove, with its futile going and coming, with its apparent indecision, with its real strictness of military discipline, was conducted. As far as Erlon is concerned, it was no more than the continual obedience of orders, or supposed orders, to which a soldier is bound. With Ney’s responsibility I shall deal in a moment.

Let me first make the matter plainer, if I can, by an illustration.

Fire breaks out in a rick near a farmer’s house and at the same time in a barn half a mile away. The farmer sends ten men with water-buckets and an engine to put out the fire at the barn, while he himself, with another ten men, but without an engine, attends to the rick. He gives to his foreman, who is looking after the barn fire, the task of giving orders to the engine, and the man at the engine is told to look to the foreman and no one else for his orders. The foreman is known to be of the greatest authority with his master. Hardly has the farmer given all these instructions when he finds that the fire in the rick has spread to his house. He lets the barn go hang, and sends a messenger to the foreman with an urgent note to send back the engine at once to the house and rick. The messenger finds the man with the engine on his way to the barn, intercepts him, and tells him that the farmer has sent orders to the foreman that the engine is to go back at once to the house. The fellow turns round with his engine and is making his way towards the house when another messenger comes posthaste from the foreman direct , telling him at all costs to bring the engine back to the barn. The man with the engine turns once more, abandons the house, but cannot reach the barn in time to save it. The result of the shilly-shally is that the barn is burnt down, and the fire at the farmer’s house only put out after it has done grave damage.

The farmer is Napoleon. His rick and house are Ligny. The foreman is Ney, and the barn is Quatre Bras. The man with the engine is Erlon, and the engine is Erlon’s command—the First Corps d’Armée.

There was no question of contradictory orders in Erlon’s mind, as many historians seem to imagine; there was simply, from Erlon’s standpoint, a countermanded order.

He had received, indeed, an order coming from the Emperor, but he had received it only as the subordinate of Ney, and only, as he presumed, with Ney’s knowledge and consent, either given or about to be given. In the midst of executing this order, he got another order countermanding it, and proceeding directly from his direct superior. He obeyed this second order as exactly as he had obeyed the first.

Such is, undoubtedly, the explanation of the thing, and Ney’s is the mind, the person, historically responsible for the whole business.

Let us consider the difficulties in the way of accepting this conclusion. The first difficulty is that Ney would not have taken it upon himself to countermand an order of Napoleon’s. Those who argue thus neither know the character of Ney nor the nature of the struggle at Quatre Bras; and they certainly underestimate both the confusion and the elasticity of warfare. Ney, a man of violent temperament (as, indeed, one might expect with such courage), was in the heat of the desperate struggle at Quatre Bras when he received Napoleon’s order to abandon his own business (a course which was, so late in the action, physically impossible). Almost at the same moment Ney heard most tardily from a messenger whom Erlon had sent (a Colonel Delcambre) that Erlon, with his 20,000 men—Erlon, who had distinctly been placed under his orders—was gone off at a tangent, and was leaving him with a grossly insufficient force to meet the rapidly swelling numbers of Wellington. We have ample evidence of the rage into which he flew, and of the fact that he sent back Delcambre with the absolutely positive order to Erlon that he should turn round and come back to Quatre Bras.

Читать дальше