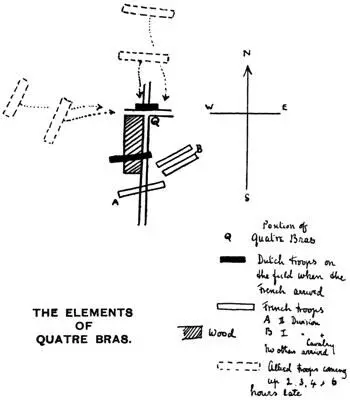

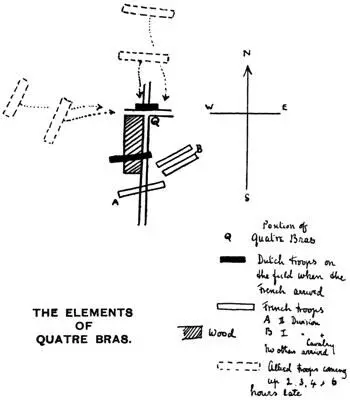

To have done with the action of Quatre Bras! But there were already superior forces before Ney! And they were increasing! If he dreamt of turning, it would be annihilation for his troops, or at the least the catching of his army’s and Napoleon’s between two fires. He might just manage when Erlon came up—and surely Erlon must appear from one moment to another—he might just manage to overthrow the enemy in front of him so rapidly as to have time to turn and appear at Ligny before darkness should fall, from three to four hours later.

It all hung on Erlon:—He might ! and at that precise moment, with his impatience strained to breaking-point, and all his expectation turned on Frasnes, whence the head of Erlon’s column should appear, there rode up to Ney a general officer, Delcambre by name. He came with a message. It was from Erlon. … Erlon had abandoned the road to Quatre Bras; had understood that he was not to join Ney after all, but to go east and help Napoleon! He had turned off eastward to the right two and a half miles back, and was by this time far off in the direction which would lead him to take part in the battle of Ligny!

Under the staggering blow of this news Ney broke into a fury. It meant possibly the annihilation of his body, certainly its defeat. He did two things, both unwise from the point of view of his own battle, and one fatal from the point of view of the whole campaign.

First, he launched his reserve cavalry, grossly insufficient in numbers for such a mad attempt, right at the English line, in a despairing effort to pierce such superior numbers by one desperate charge. Secondly, he sent Delcambre back—not calculating distance or time—with peremptory orders to Erlon, as his subordinate, to come back at once to the battlefield of Quatre Bras.

There was, as commander to lead that cavalry charge, Kellerman. He had but one brigade of cuirassiers: two regiments of horse against 25,000 men! It was an amazing ride, but it could accomplish nothing of purport. It thundered down the slope, breaking through the advancing English troops (confused by a mistaken order, and not yet formed in square), cut to pieces the gunners of a battery, broke a regiment of Brunswickers near the top of the hill, and reached at last the cross-roads of Quatre Bras. Five hundred men still sat their horses as the summit of the slope was reached. The brigade had cut a lane right through the mass of the defence; it had not pierced it altogether.

Some have imagined that if at that moment the cavalry of the Guard, which was still in reserve, had followed this first charge by a second, Ney might have effected his object and broken Wellington’s line. It is extremely doubtful, the numbers were so wholly out of proportion to such a task. At any rate, the order for the second charge, when it came, came somewhat late. The five hundred as they reined up on the summit of the hill were met and broken by a furious cross-fire from the Namur road upon the right, from the head of Bossu Wood upon the left, while yet another unit, come up in this long succession to reinforce the defence—a battery of the King’s German Legion—opened upon them with grape. The poor remnant of Kellerman’s Horse turned and galloped back in confusion.

The second cavalry charge attempted by the French reserve, coming just too late, necessarily failed, and at the same moment yet another reinforcement—the first British division of the Guards, and a body of Nassauers, with a number of guns—came up to increase the now overwhelming superiority of Wellington’s line. 10

There was even an attempt at advance upon the part of Wellington.

As the evening turned to sunset, and the sunset to night, that advance was made very slowly and with increasing difficulty—and all the while Ney’s embarrassed force, now confronted by something like double its own numbers, and contesting the ground yard by yard as it yielded, received no word of Erlon.

The clearing of the Wood of Bossu by the right wing of Wellington’s army, reinforced by the newly arrived Guards, took more than an hour. It took as long to push the French centre back to Gemioncourt, and all through the last of the sunlight the walls of the farm were desperately held. On the left, Pierrepont was similarly held for close upon an hour. The sun had already set when the Guards debouched from the Wood of Bossu, only to be met and checked by a violent artillery fire from Pierrepont, while at the same time the remnant of the cuirassiers charged again, and broke a Belgian battalion at the edge of the wood.

By nine o’clock it was dark and the action ceased. Just as it ceased, and while, in the last glimmerings of the light, the major objects of the landscape, groups of wood and distant villages, could still be faintly distinguished against the background of the gloom, one such object seemed slowly to approach and move. It was first guessed and then perceived to be a body of men: the head of a column began to debouch from Frasnes. It was Erlon and his 20,000 returned an hour too late.

All that critical day had passed with the First Corps out of action. It had neither come up to Napoleon to wipe out the Prussians at Ligny, nor come back in its countermarch in time to save Ney and drive back Wellington at Quatre Bras. It might as well not have existed so far as the fortunes of the French were concerned, and its absence from either field upon that day made defeat certain in the future, as the rest of these pages will show.

* * * * *

Two things impress themselves upon us as we consider the total result of that critical day, the 16th of June, which saw Ney fail to hold the Brussels road at Quatre Bras, and there to push away from the advance on Brussels Wellington’s opposing force, and which also saw the successful escape of the Prussians from Ligny, an escape which was to permit them to join Wellington forty-eight hours later and to decide Waterloo.

The first is the capital importance, disastrous to the French fortunes, of Erlon’s having been kept out of both fights by his useless march and countermarch.

The Elements of Quatre Bras.

The second is the extraordinary way in which Wellington’s command came up haphazard, dribbling in by units all day long, and how that command owed to Ney’s caution and tardiness, much more than to its own General’s arrangements, the superiority in numbers which it began to enjoy from an early phase in the battle.

I will deal with these two points in their order.

* * * * *

As to the first:—

The whole of the four days of 1815, and the issue of Waterloo itself, turned upon Erlon’s disastrous counter-marching between Quatre Bras and Ligny upon this Friday, the 16th of June, which was the decisive day of the war.

What actually happened has been sufficiently described. The useless advance of Erlon’s corps d’armée towards Napoleon and the right—useless because it was not completed; the useless turning back of that corps d’armée towards Ney and the left—useless because it could not reach Ney in time—these were the determining factors of that critical moment in the campaign.

In other words, Erlon’s zigzag kept the 20,000 of the First Corps out of action all day. Had they been with Ney, the Allies under Wellington at Quatre Bras would have suffered a disaster. Had they been with Napoleon, the Prussians at Ligny would have been destroyed. As it was, the First Army Corps managed to appear on neither field. Wellington more than held his own; the Prussians at Ligny escaped, to fight two days later at Waterloo.

Читать дальше