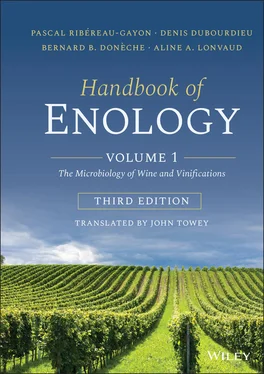

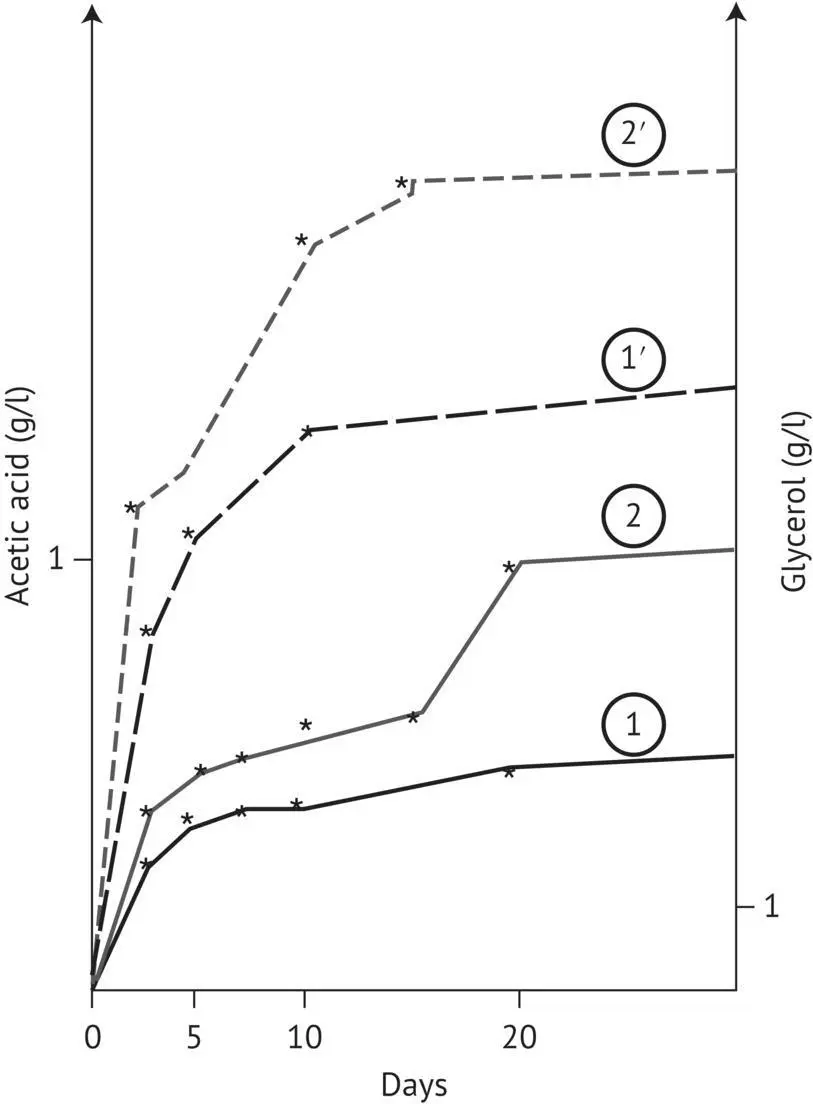

FIGURE 2.15 Effect of an alcohol‐induced precipitate of a botrytized grape must on glycerol and acetic acid formation during the alcoholic fermentation of healthy grape must (Dubourdieu, 1982). 1, Evolution of acetic acid concentration in the control must; 2, evolution of acetic acid concentration in the must supplemented with the freeze‐dried precipitate; 1′, evolution of glycerol concentration in the control must; 2′, evolution of glycerol concentration in the must supplemented with the freeze‐dried precipitate.

Other winemaking factors favor the production of acetic acid by S. cerevisiae : anaerobic conditions, very low pH ( < 3.1) or very high pH (>4), certain amino acid or vitamin deficiencies in the must, and excessively high temperature (25–30°C) during the yeast growth phase. In red winemaking, temperature is the most important factor, especially when the must has a high sugar concentration. In hot climates, the grapes should be cooled when filling the tanks. The temperature should not exceed 20°C at the beginning of fermentation. The same procedure should be followed during thermovinification immediately following the heating of the grapes.

In dry white and rosé winemaking, excessive must clarification can also lead to the excessive production of volatile acidity by yeast. This phenomenon can be particularly pronounced with certain yeast strains. Therefore, must turbidity should be adjusted to the lowest possible level that enables a complete and rapid fermentation (Sections 3.7.3 and 13.5.3). The input of lipids made available to yeasts via solid sediments (grape solids), in particular long‐chain unsaturated fatty acids (C18:1 and C18:2), greatly influences acetic acid production during white and rosé winemaking.

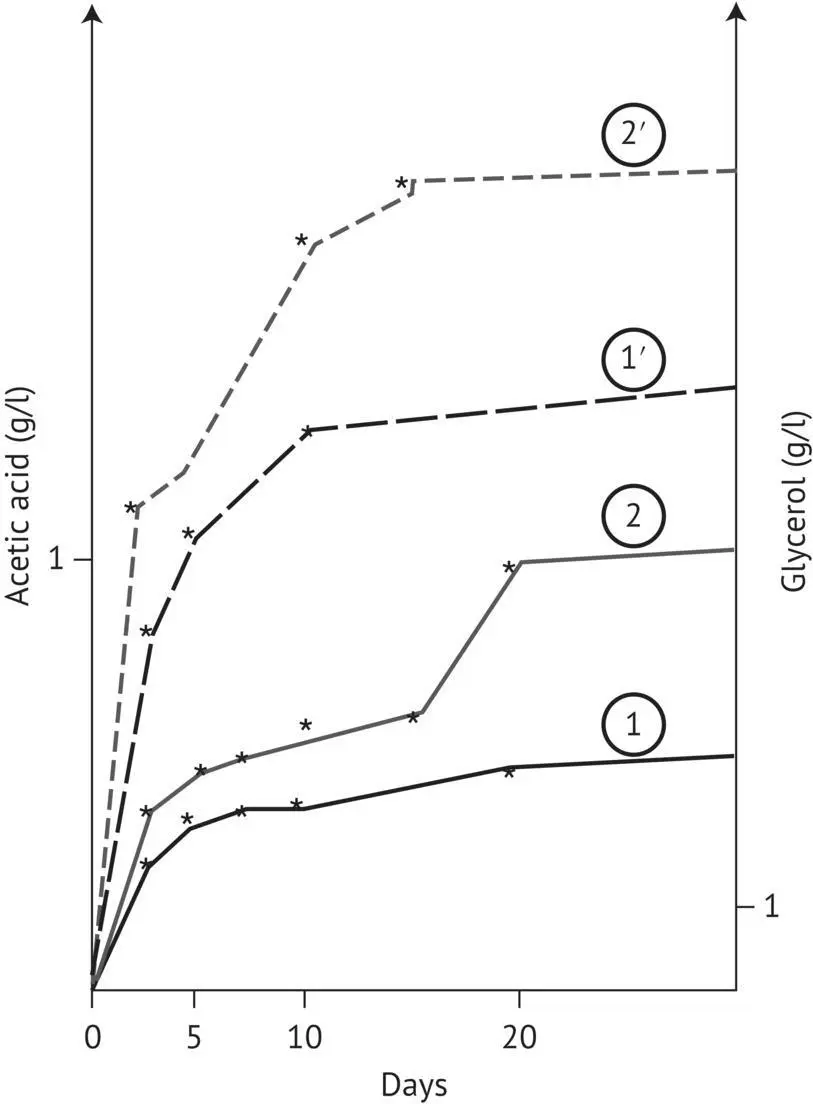

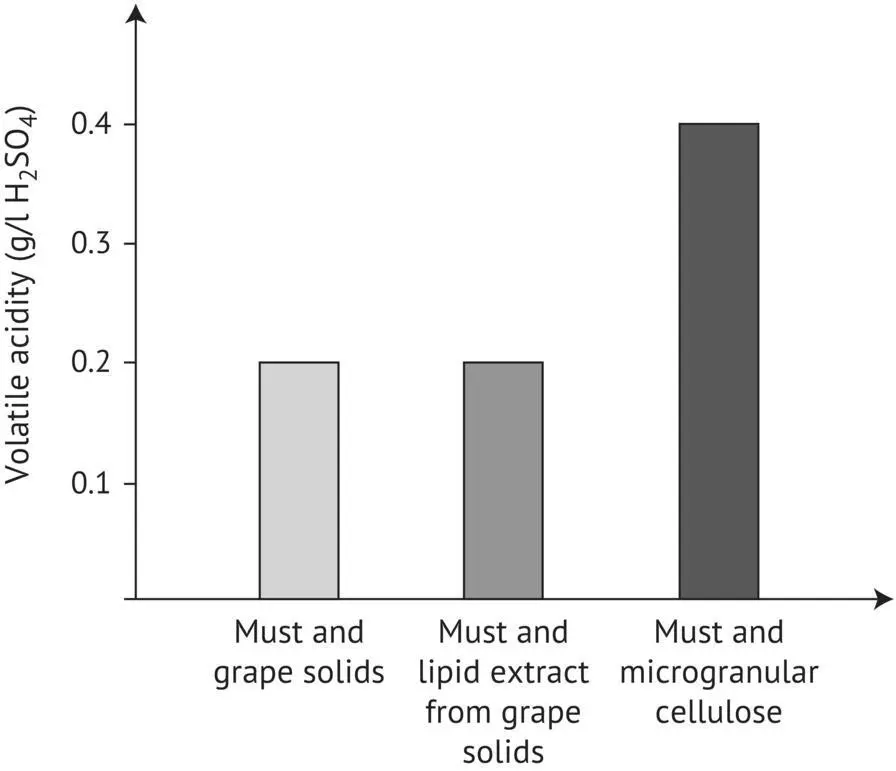

The experiment in Figure 2.16illustrates the important role of lipids in acetic acid metabolism (Delfini and Cervetti, 1992; Alexandre et al ., 1994). The volatile acidity of three wines obtained from the same Sauvignon Blanc must was compared. After filtration but before yeast inoculation, must turbidity was adjusted to 250 Nephelometric Turbidity Units (NTU) by three different methods: reincorporating fresh grape solids (control), adding cellulose powder, and supplementing with a lipid extract (using methanol–chloroform) that contained the same quantity of grape solids adsorbed on the cellulose powder. The volatile acidities of the control wine and the wine that was supplemented with a lipid extract of grape solids before fermentation are identical and perfectly normal. Although the fermentation was normal, the volatile acidity of the wine made from the must supplemented with cellulose (therefore devoid of lipids) was practically twice as high (Lavigne, 1996). Supplementing the medium with lipids appears to favor the penetration of amino acids into the cell, which limits the formation of acetic acid.

FIGURE 2.16 Effect of the lipid fraction of grape solids on acetic acid production by yeasts during alcoholic fermentation (Lavigne, 1996).

During the alcoholic fermentation of red or slightly clarified white wines, yeasts do not continuously produce acetic acid. The yeast metabolizes a large portion of the acetic acid secreted in must during the fermentation of the first 50–100 g of sugar. It can also assimilate acetic acid added to must at the beginning of alcoholic fermentation. The assimilation mechanisms are not yet clear. Acetic acid appears to be reduced to acetaldehyde, which favors alcoholic fermentation to the detriment of glyceropyruvic fermentation. In fact, the addition of acetic acid to a must lowers glycerol production but increases the formation of acetoin and 2,3‐butanediol. Yeasts seem to use the acetic acid formed at the beginning of alcoholic fermentation (or added to must) via acetyl‐CoA in their lipid synthesis pathways.

Certain winemaking conditions produce abnormally high amounts of acetic acid. Since this acid is not used during the second half of the fermentation, it accumulates until the end of fermentation. When refermenting a tainted wine, yeasts can lower volatile acidity by metabolizing acetic acid. The wine is incorporated into freshly crushed grapes at a proportion of no more than 20–30%. The wine should be sulfited or filtered before incorporation to eliminate bacteria. The volatile acidity of this mixture should not exceed 0.6 g/l expressed as H 2SO 4. The volatile acidity of this newly made wine rarely exceeds 0.3 g/l expressed as H 2SO 4. The concentration of ethyl acetate decreases simultaneously.

2.3.5 Other Secondary Products of the Fermentation of Sugars

Lactic acid is another secondary product of fermentation. It is also derived from pyruvic acid, which is directly reduced by yeast L(+)‐ and D(−)‐lactate dehydrogenases. Under anaerobic conditions (the case in alcoholic fermentation), the yeast synthesizes predominantly D(−)‐lactate dehydrogenase. Yeasts form 200–300 mg of D(−)‐lactic acid per liter and only a few dozen milligrams of L(+)‐lactic acid. The latter is formed essentially at the start of fermentation. By determining the D(−)‐lactic acid concentration in a wine, it can be ascertained whether the origin of acetic acid is yeast or lactic acid bacteria (Section 14.2.3). Wines that have undergone malolactic fermentation can contain several grams per liter of exclusively L(+)‐lactic acid. On the other hand, the lactic acid fermentation of sugars (lactic spoilage) forms D(−)‐lactic acid. When D(−)‐lactic acid concentrations exceed 200–300 mg/l, it is clear that lactic acid bacteria have transformed substrates other than malic acid.

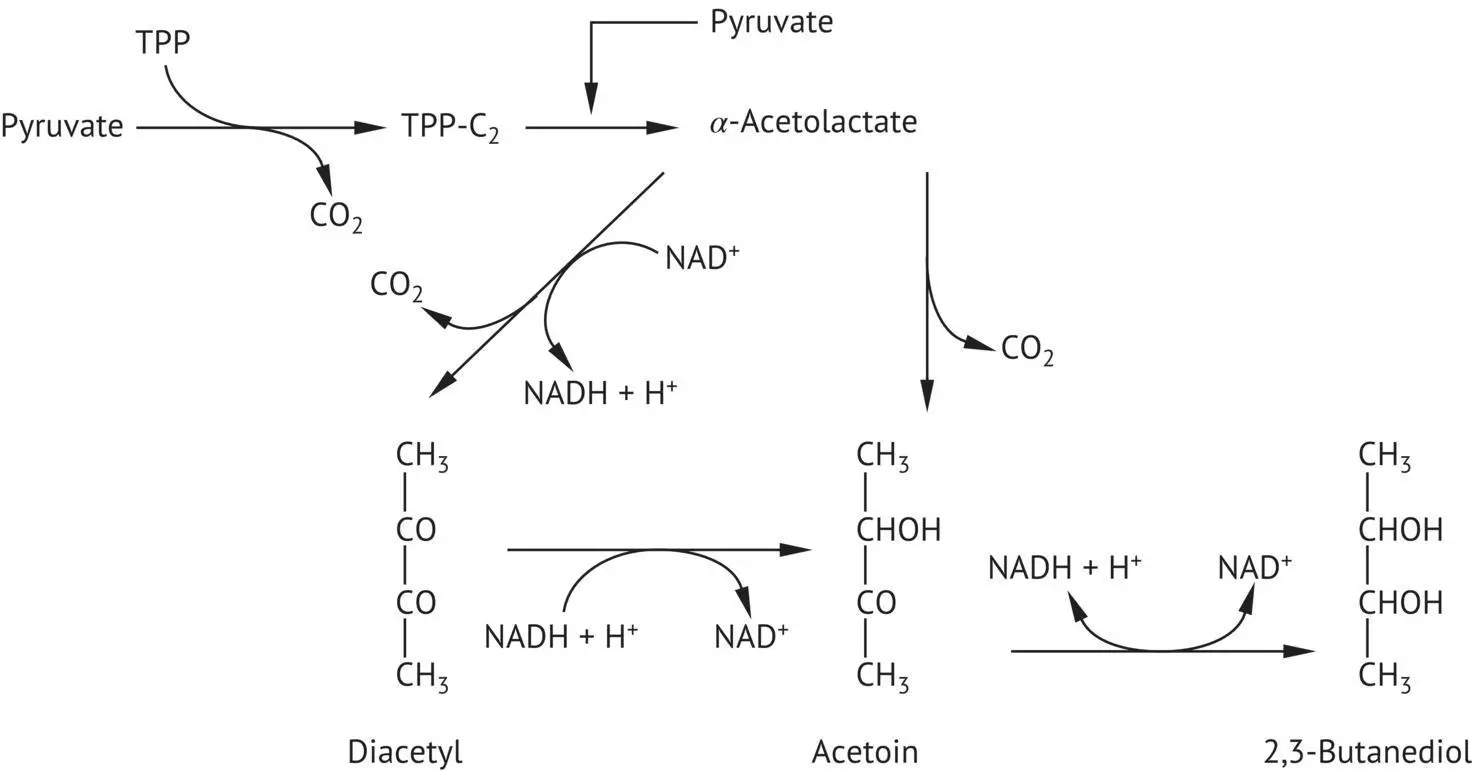

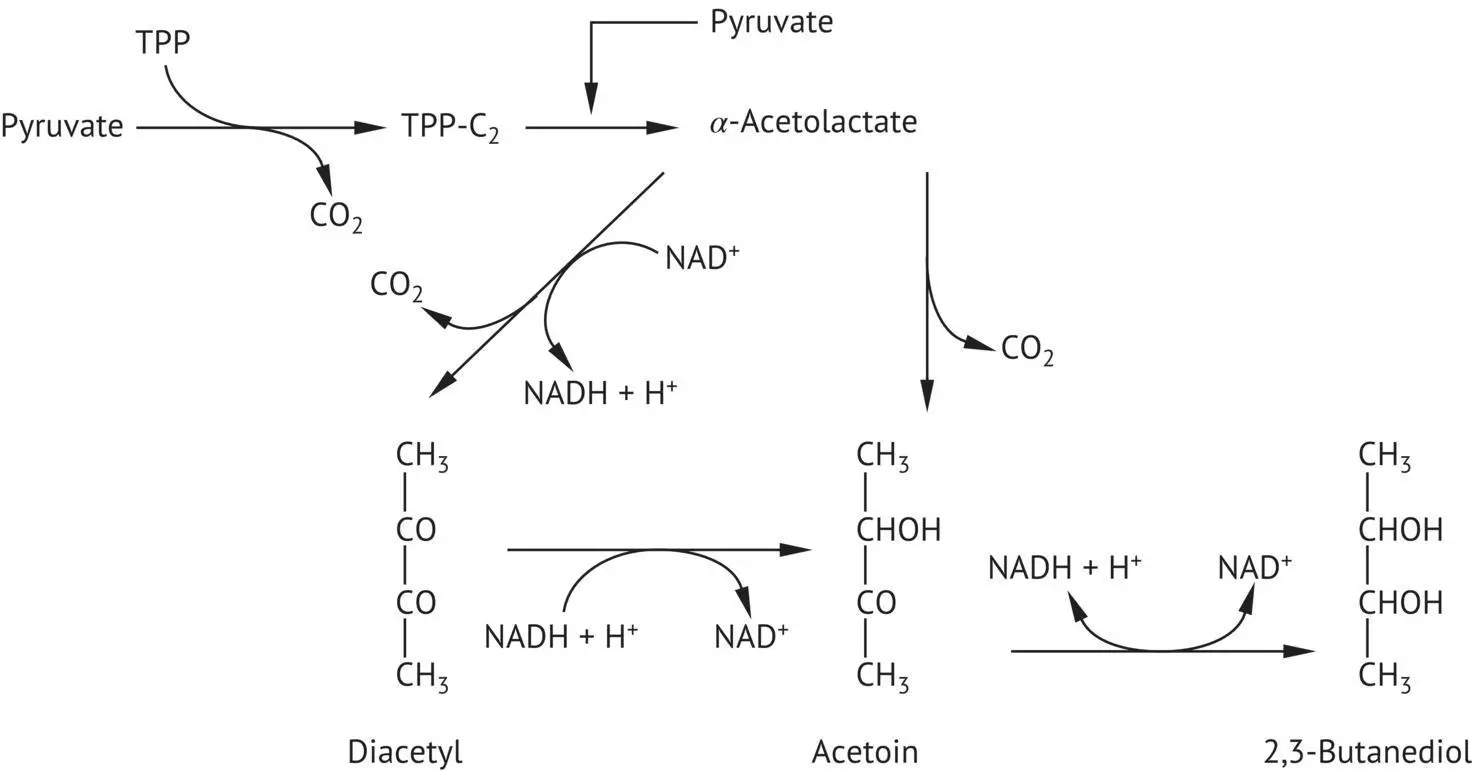

FIGURE 2.17 Acetoin, diacetyl, and 2,3‐butanediol formation by yeasts under anaerobic conditions. TPP, thiamine pyrophosphate; TPP‐C 2, active acetaldehyde.

Yeasts also make use of pyruvic acid to form acetoin, diacetyl, and 2,3‐butanediol ( Figure 2.17). This process begins with the condensation of a pyruvate molecule and a molecule of active acetaldehyde bound to TPP, leading to the formation of α ‐acetolactic acid. The oxidative decarboxylation of α ‐acetolactic acid produces diacetyl. Acetoin is produced by either the non‐oxidative decarboxylation of α ‐acetolactic acid or the reduction of diacetyl. The reduction of acetoin leads to the formation of 2,3‐butanediol; this last reaction is reversible.

From the start of alcoholic fermentation, yeasts produce diacetyl, which is rapidly reduced to acetoin and 2,3‐butanediol. This reduction takes place in the days that follow the end of alcoholic fermentation, when wines are conserved on the yeast biomass (de Revel et al ., 1996). Acetoin and especially diacetyl are strong‐smelling compounds that evoke a buttery aroma. Above a certain concentration, they have a negative effect on wine aroma. However, in wines that have not undergone malolactic fermentation, their concentration is too low (a few milligrams per liter for diacetyl) to have a sensory impact. On the other hand, lactic acid bacteria can degrade citric acid to produce much higher quantities of these carbonyl compounds than yeasts (Section 5.3.2).

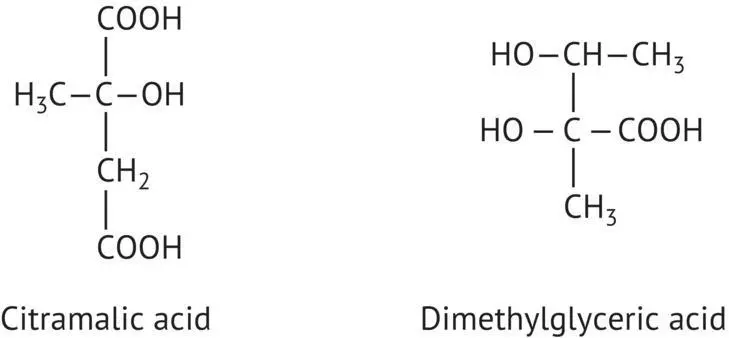

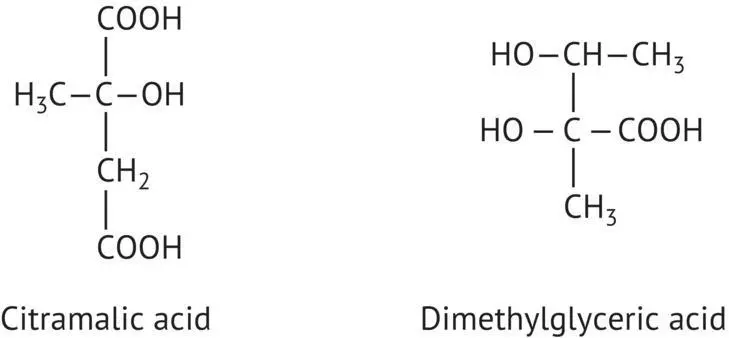

FIGURE 2.18 Citramalic acid and dimethylglyceric acid.

Читать дальше