All of the results of molecular taxonomy presented above show that the former phenotypic classifications, based on physiological identification criteria, are not suitable even for delimiting the small number of fermentative species of the Saccharomyces genus found in winemaking. Moreover, specialists have long known about the instability of the physiological properties of Saccharomyces strains. Rossini et al . (1982) reclassified a thousand strains from the yeast collection of the Microbiology Institute of Agriculture at the University of Perugia. They observed that 23 out of 591 S. cerevisiae strains conserved on malt agar had lost the ability to ferment galactose. The use of genetic methods is thus essential to identify winemaking yeasts.

1.8.4 Interspecific Hybrids

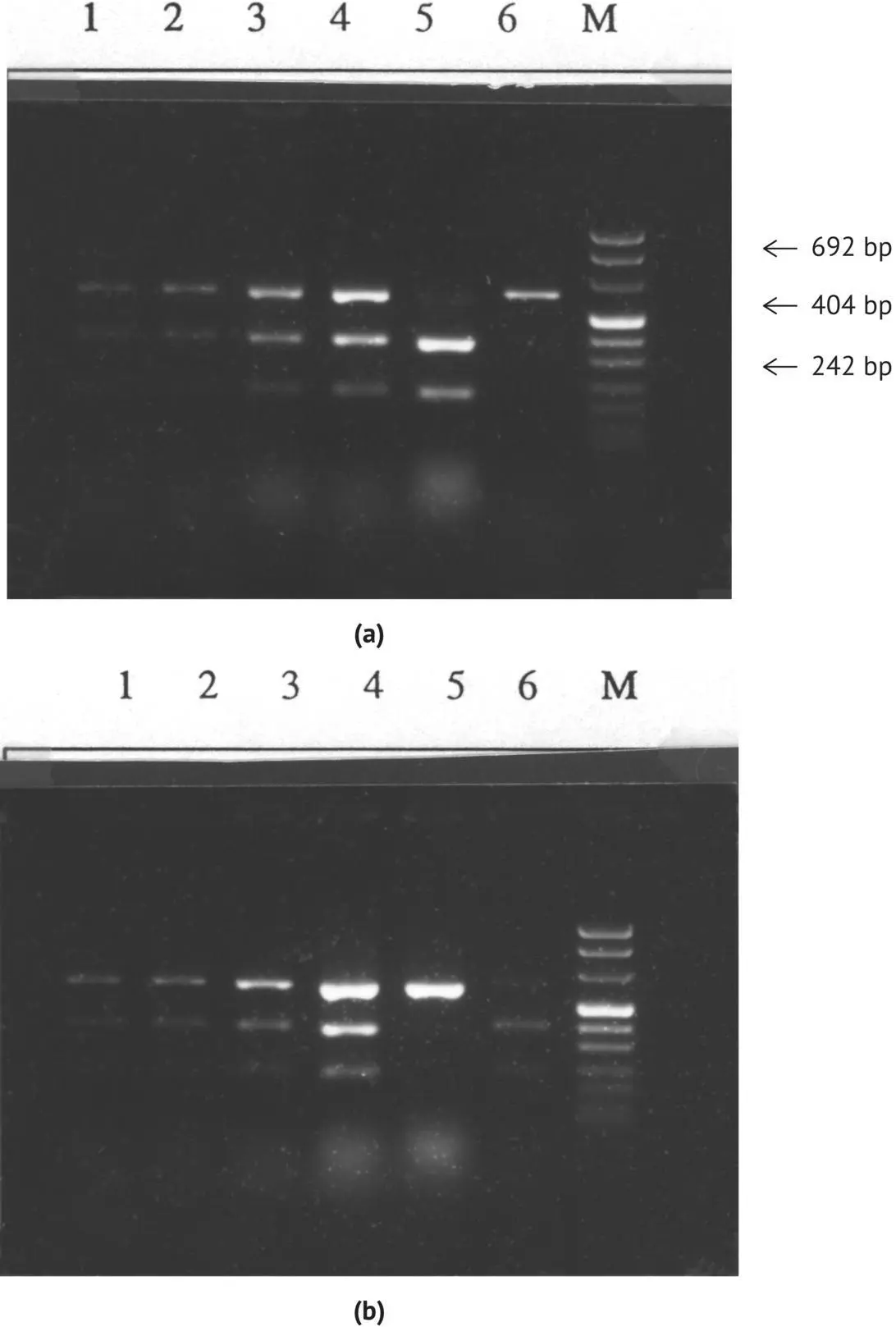

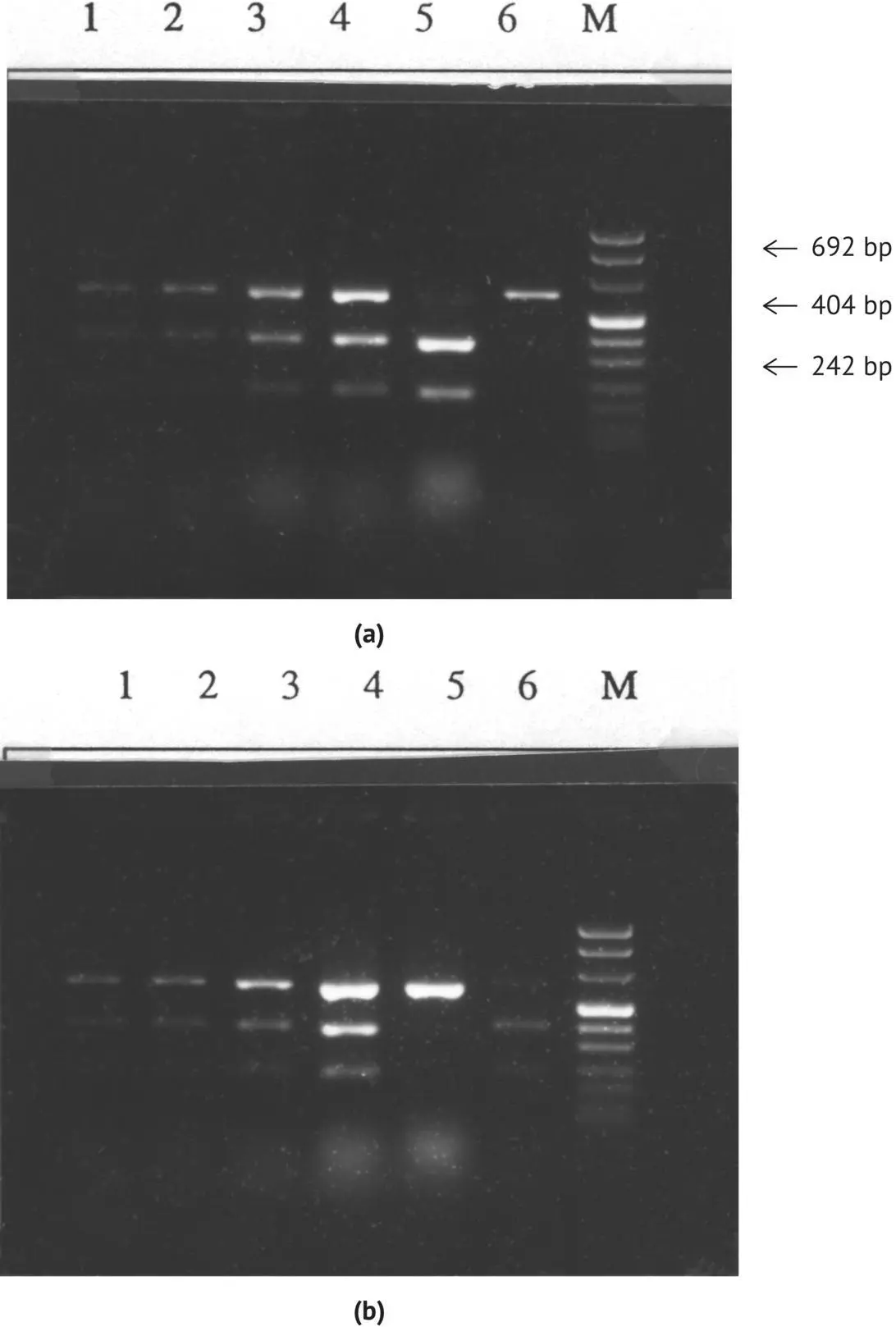

PCR‐RFLP associated with the MET 2 gene can be used to demonstrate the existence of hybrids between the species S. cerevisiae and S. uvarum . This method has been used to prove the existence (Masneuf et al ., 1998) of one such natural hybrid (strain S6U) among commercial dry yeasts sold by Lallemand Inc. (Montreal, Canada). Ciolfi (1992, 1994) isolated this yeast in an Italian winery, and it was selected for certain enological properties, in particular its aptitude to ferment at low temperatures, its low production of acetic acid, and its ability to preserve must acidity. The MET 2 gene restriction profiles of this strain by Eco R1 and Pst 1, composed of three bands, are identical ( Figure 1.25). In addition to the amplified fragment, two bands characteristic of S. cerevisiae with Eco R1 and two bands characteristic of the species S. bayanus with Pst 1 are obtained. The bands are not artifacts due to an impurity in the strain, because the amplification of the MET 2 gene carried out on subclones (obtained from the multiplication of unique cells isolated by a micromanipulator) produces identical results. Hansen from the Carlsberg laboratory (Denmark) sequenced two of the MET 2 gene alleles from this strain. The sequence of one of the alleles is identical to that of the S. cerevisiae MET 2 gene, with the exception of one nucleotide. The sequence of the other allele is 98.5% similar to that of S. uvarum . The presence of this allele is thus probably due to an interspecific cross.

Subsequently, more recent research (Naumov et al ., 2000b) has shown that the S6U strain is, in fact, a tetraploid hybrid. Indeed, the percentage germination of spores from 24 tetrads, isolated using a micromanipulator, was very high (94%), whereas it would have been very low for a “normal” diploid interspecific hybrid. The monospore clones in this first generation (D1) were all capable of sporulating. However, none of the ascospores of the second‐generation tetrads was viable. The hybrid nature of the monospore clones produced by D1 was confirmed by the presence of the S. cerevisiae and S. uvarum MET 2 gene, identified by PCR/RFLP. Finally, measuring the DNA content per cell using flux cytometry estimation confirmed that the descendants of S6U were interspecific diploids and that S6U itself was an allotetraploid.

FIGURE 1.25 Electrophoresis in agarose gel (1.8%) of (a) Eco R1 and (b) Pst 1 digestions of the amplified fragments of the MET 2 gene of the hybrid strain. Bands 1, 2, 3, subclones of the hybrid strain; band 4, hybrid strain; band 5, S. cerevisiae control; band 6, S. uvarum control; M, molecular weight marker.

The molecular characterization of wine yeasts isolated on grapes and in must undergoing spontaneous fermentation revealed the existence of many natural hybrids between S. cerevisiae and S. uvarum (Le Jeune et al ., 2007). This is also true between S. cerevisiae and Saccharomyces kudriavzevii (Sipiczki, 2008; Arroyo‐López et al ., 2009; Erny et al ., 2012). Interspecific hybridization leads to new gene combinations in a given cell and may confer a selective advantage with respect to parental strains. Interspecific hybrids possess interesting technological properties for winemaking. For example, S. uvarum and S. kudriavzevii are better adapted to low‐temperature growth, and S. cerevisiae presents high tolerance to ethanol. Natural hybrids between these species are more adapted to growth in a large range of temperatures and at high ethanol concentrations, thanks to the genetic heritage of one or both parents, thus yielding properties of interest (Da Silva et al ., 2015). This mechanism for acquiring superior phenotypic characteristics in hybrid descendants during cross‐breeding of parental strains is well described in plants. This is called a heterosis effect.

1.9 Identification of Wine Yeast Strains

1.9.1 General Principles

The principal yeast species involved in grape must fermentation, particularly S. cerevisiae and S. uvarum , comprise a very large number of strains with extremely varied technological properties. The yeast strains involved during winemaking influence fermentation speed, the nature and quantity of secondary products formed during alcoholic fermentation, and the aroma characteristics of the wine. The ability to differentiate between the different strains of S. cerevisiae is required for the following fields: the ecological study of wild yeasts responsible for the spontaneous fermentation of grape must, the selection of strains presenting the best enological qualities, production and marketing controls, the verification of the implantation of selected yeasts used as yeast starter, and the constitution and maintenance of wild or selected yeast collections.

The initial research on infraspecific differentiation within S. cerevisiae attempted to distinguish strains by electrophoretic analysis of their exocellular (Bouix et al ., 1981) or intracellular (Van Vuuren and Van Der Meer, 1987) proteins or glycoproteins. Other teams proposed identifying the strains by the analysis of long‐chain fatty acids using gas chromatography (Tredoux et al ., 1987; Augustyn et al ., 1991; Bendova et al ., 1991; Rozes et al ., 1992). Although these different techniques differentiate between certain strains, they are irrefutably less discriminating than genetic differentiation methods. They also present the major drawback of depending on the physiological state of the strains and on cultural conditions, which must always be identical.

In the late 1980s, owing to the development of genetics, certain techniques from molecular biology were successfully applied to characterize wine yeast strains. They are based on the clonal polymorphism of the mitochondrial and genomic DNA of S. cerevisiae and S. uvarum . These genetic methods are independent of the physiological state of the yeast, unlike the previous techniques based on the analysis of metabolism by‐products.

1.9.2 Mitochondrial DNA Analysis

The mtDNA of S. cerevisiae has two remarkable properties: it is extremely polymorphic, depending on the strain; and stable (it mutates very little) during vegetative reproduction. Restriction endonucleases (such as Eco R5) cut this DNA at specific sites. This process generates fragments of variable size that are few in number and can be separated by electrophoresis on agarose gel.

Aigle et al . (1984) first applied this technique to brewer's yeasts. Since 1987, it has been used for the characterization of enological strains of S. cerevisiae (Dubourdieu et al ., 1987; Hallet et al ., 1988).

Читать дальше