You Look Like an Ape: Primate Species

Biologically speaking, you’re an ape. So am I, and so is everyone else in the world. It’s true. This section shows you the general characteristics of all primates and then focuses in on the main groupings of primates, including the apes.

What’s in a name? General primate characteristics

As primates evolved after 65 million years ago, they developed the more distinctive characteristics seen in the living species as well as their fossil ancestors. Today, although the many kinds of primates vary a great deal, they do share some basic traits:

Wide range of body size, from 100 grams (1⁄3pound) to 200 kilograms (more than 400 pounds). On average, primates are about 10 pounds, which is a little larger than most rodents and a little smaller than most hoofed animals.

Large eyes with three-dimensional vision, allowing keen depth perception.

Lack of emphasis on a snout. Primates focus on vision rather than sense of smell, which appears in other animals’ snouts.

Large brain case containing the largest brain — relative to body size — of any land animal.

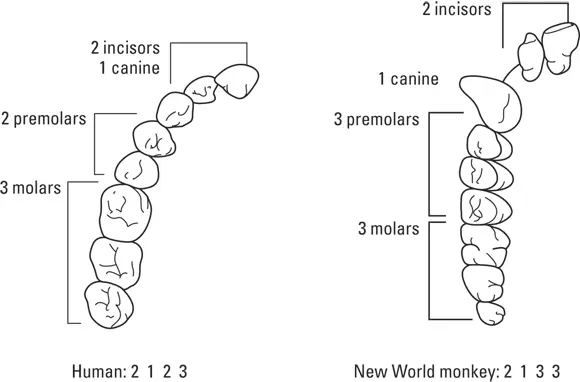

Heterodont (differentiated) teeth, indicating a varied diet. For example, the incisors can clip one kind of food, and the molars can crush another.

Nails rather than claws, allowing more sensitive grasping of tree limbs.

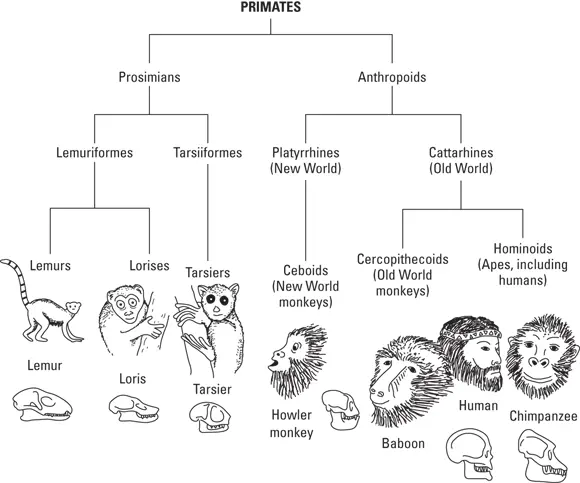

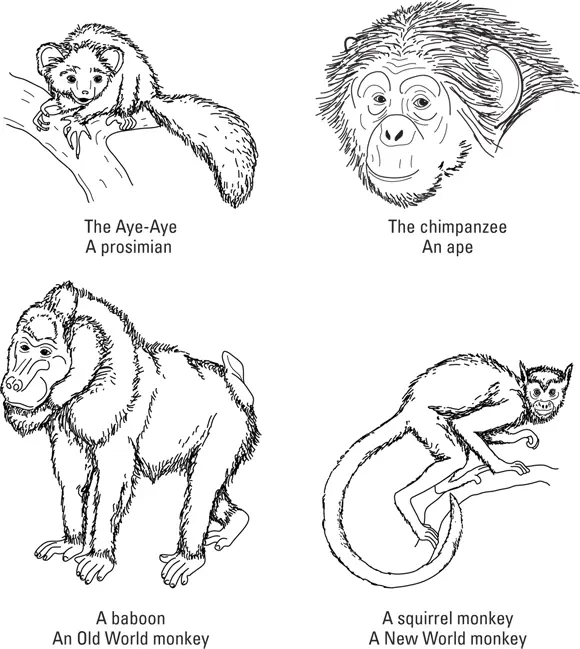

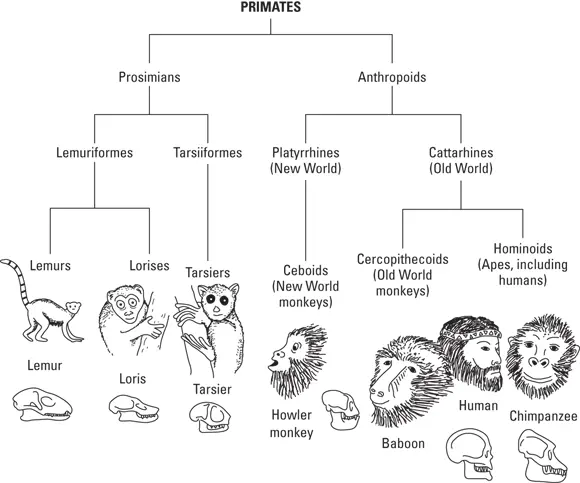

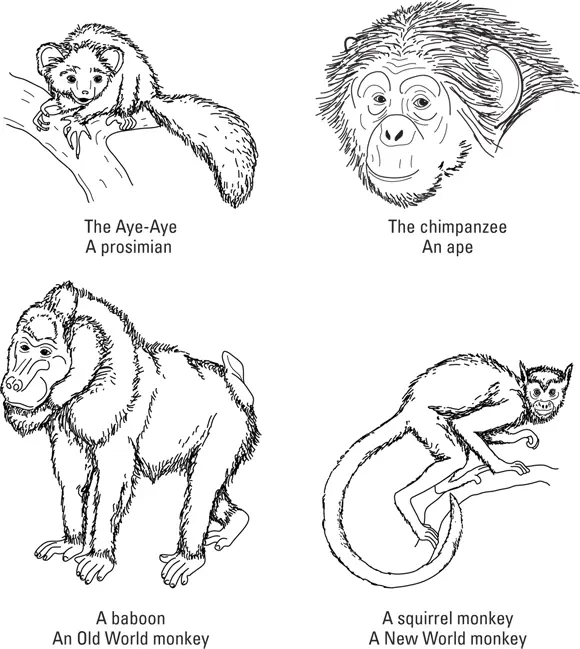

Today, the primate order contains about 230 living primate species (give or take a few, depending on whom you ask). Although you could spend a lifetime studying them in all their diversity (not to mention the fossil record of the ancestry of each living species), for most purposes it’s enough to recognize four main subgroups in the primate order: the prosimians, the Old World monkeys, the New World monkeys, and the apes. I take a closer look at these subgroups in the following sections. You can see how they relate to one another in Figure 4-2 (refer to the nearby sidebar for a refresher on biological classification), and Figure 4-3 shows how some of them appear. Regarding Figure 4-2, note that different physical anthropologists classify the primates in slightly different ways, and some don’t even consider the loris — shown in this figure but not discussed in the text — a primate. Although variations like this exist, the classification shown here is widely used.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 4-2:The Primate order.

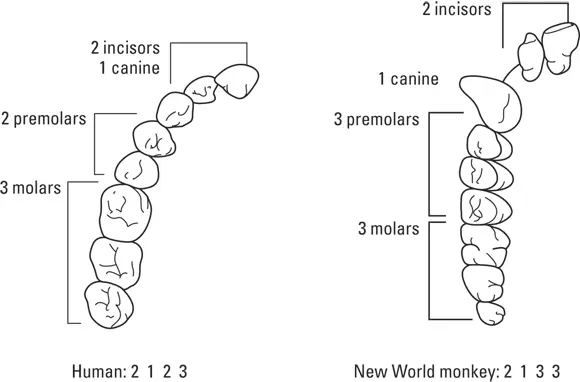

The primate dental formula is a notation of the number of various tooth types in the individual mouth, counting incisors, canines, premolars, and molars, in each quadrant of the mouth (upper left, upper right, lower left, and lower right). Different dental formulas can tell anthropologists about the relationships between species. For example, humans have two incisors, one canine, two premolars and three molars, for a dental formula of 2.1.2.3, whereas New World monkeys (a very different group) have an extra premolar, for a formula of 2.1.3.3. Figure 4-4 compares the dental formulas of an Old World ape and a New World monkey.

Although you read lists of separate species characteristics, like body weight or diet, those characteristics always intertwine. Therefore, diet can have effects on body weight and vice versa, and exactly how one characteristic affects another isn’t always easy to understand. In fact, I’d say that although anthropology today has very good lists of these characteristics and can very clearly describe the primate species, as a field anthropology doesn’t always have a good explanation for how the characteristics interact. That doesn’t mean that anthropology can’t ever understand them, but at the moment I’d say that anthropologists are just now working out the interactions of the anatomical and behavioral characteristics.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 4-3:Sketches of the main varieties of primates.

Illustration courtesy of Cameron M. Smith, PhD

FIGURE 4-4:Comparison of the dental formula of a New World monkey and an Old World ape (human).

YOU CAN’T GO HOME AGAIN

YOU CAN’T GO HOME AGAIN

An adaptive radiation is the adaptation of a species to a new environment. When new environments open up — for example, when a land bridge connects two previously separated continents or islands — life forms normally migrate into these new environments. If they survive, the colonists adapt to the new ecological conditions and, over evolutionary time, become adapted to those conditions. When the colonists are so different from their ancestral population (the ones who didn’t cross the land bridge, for example) that they can no longer interbreed with those ancestral forms, speciation has occurred.

Going ape (and prosimian): Primate subgroups

All the primates have the characteristics I mention in the preceding section, but even a quick look at the primates reveals some clear divisions. The following sections describe the four main kinds of primates.

Squirrel-cats: The prosimians

One of the major divisions in the Primate order is that between the Anthropoidea (the people-like apes and monkeys) and the Prosimii (or prosimians, which are pretty different from people even though they’re clearly primates). Baboons, chimpanzees, and gorillas — all in the Anthropoidea — are very obviously similar to humans, but connecting to, say, the ring-tailed lemur (a cat-like prosimian of Madagascar that has a long, striped tail) or the tiny, bug-eyed, shrew-like tarsier that can fit in the palm of your hand is a little more difficult. Still, these animals are primates — even though they can look like a cross between a squirrel and a cat — and they typically have the following distinctive traits:

Relatively long snouts in some species (long for primates, anyway), although they may also have very large eyes

A dental formula of 2.1.3.3

Small body size compared to other primates; they range from mouse-size to cat-size, averaging about 5 kilograms or 10 pounds

Some are nocturnal and have a diet that favors insects but includes tree saps, grubs, fruit, flowers, and leaves

Nocturnal animals are most active at night, whereas diurnal species are most active in daylight. Making a living in darkness or light has effects on what foods animals eat, how they avoid predators, how they move about their environment, and so on.

Nocturnal animals are most active at night, whereas diurnal species are most active in daylight. Making a living in darkness or light has effects on what foods animals eat, how they avoid predators, how they move about their environment, and so on.

Probably the strangest primate is the aye-aye of Madagascar. About the size of a cat with enormous, hairless ears, the aye-aye climbs through trees by moonlight listening for larvae beneath tree bark. When it hears a squirming treat, it uses a thin, elongated finger to scoop the meal out of the bark. Even the driest textbooks of primatology can’t help but marvel over this creature, which one author called the most “improbable” primate; another said that the aye-aye, though clearly a primate, displayed the most extreme specialization of anatomy in the order. This means that although most primates are somewhat general in their diet (many have a varied, omnivorous diet), the aye-aye is quite specialized and inflexible in its diet. Unfortunately, such specialization can prove disastrous if the prey species itself becomes extinct or somehow declines.

Читать дальше

YOU CAN’T GO HOME AGAIN

YOU CAN’T GO HOME AGAIN Nocturnal animals are most active at night, whereas diurnal species are most active in daylight. Making a living in darkness or light has effects on what foods animals eat, how they avoid predators, how they move about their environment, and so on.

Nocturnal animals are most active at night, whereas diurnal species are most active in daylight. Making a living in darkness or light has effects on what foods animals eat, how they avoid predators, how they move about their environment, and so on.