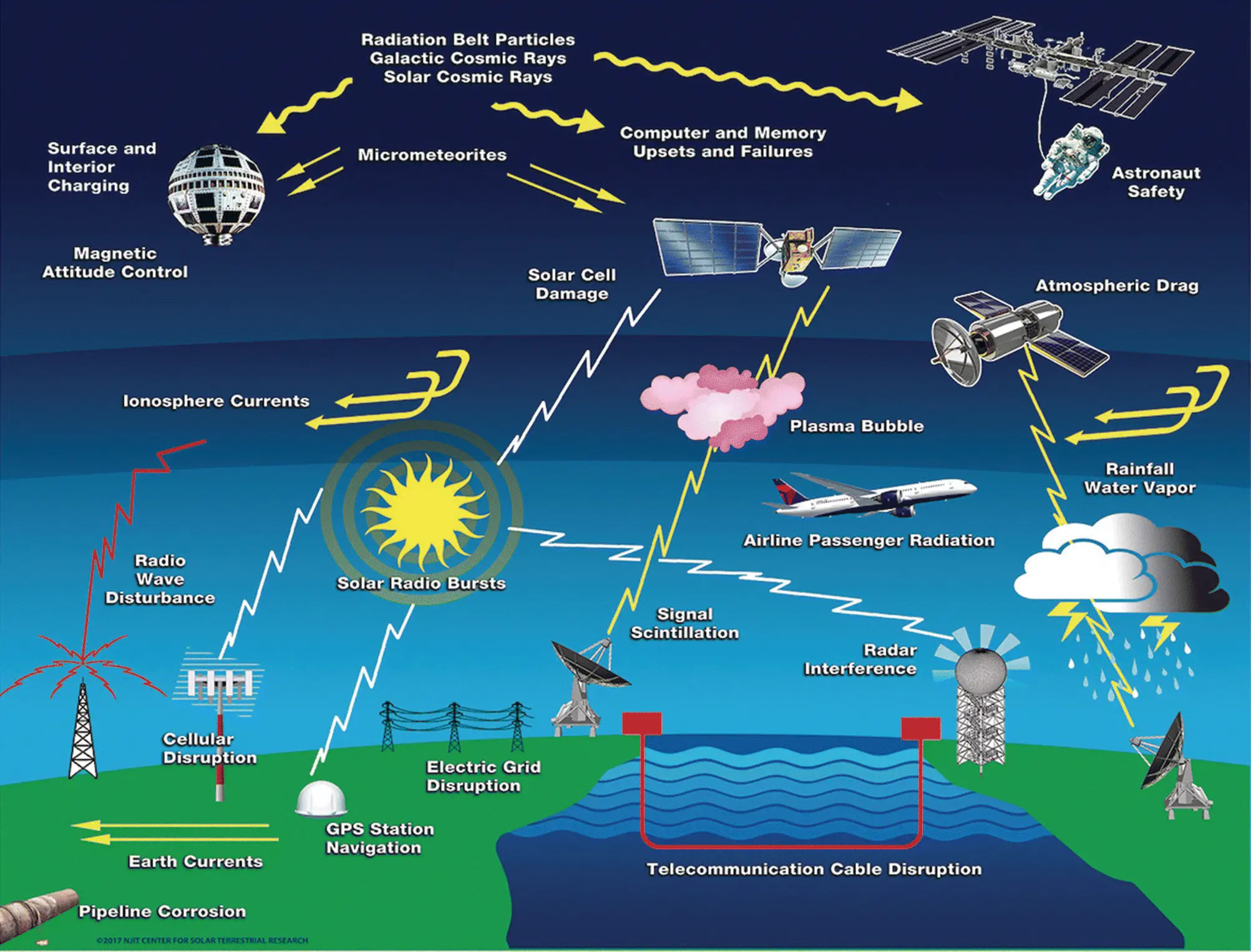

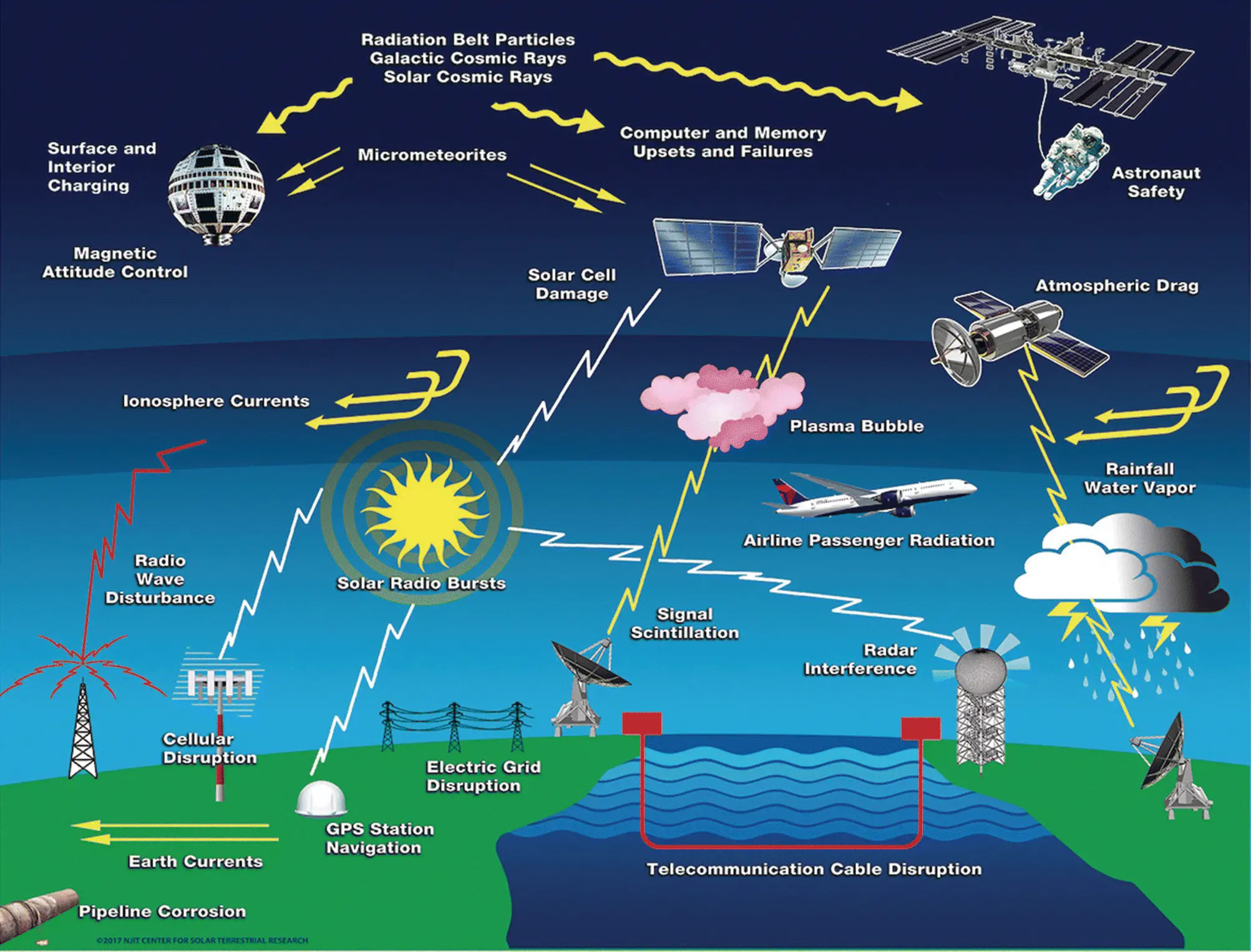

Successful operations of increasingly sophisticated technical systems require increasingly detailed understanding of solar and terrestrial space phenomena. This has been accomplished by the access to space provided by increasingly reliable launch vehicles since the late 1950s. Ever more sophisticated instrumentation has been deployed to measure Earth’s space environment. The data acquired can be incorporated into ever better models to describe and even forecast the environment and its changes. This also has the complementary result of better understanding the effects of the environment on contemporary technologies.

This volume was designed to provide a topical discussion of current day technologies and how they are affected by solar and terrestrial space processes. Without these technologies, contemporary life in civil, commercial, and national security realms would be very different, and indeed impossible. Access to space has also meant that humans can now live, with appropriate support systems, above the sensible atmosphere. Thus, a closely related topic, also covered in this volume, involves the many issues related to human survival in the space radiation environment inside and outside Earth’s magnetosphere. These issues deserve serious consideration prior to the planning and execution of projects involving a significant human presence in interplanetary space.

1 Barlow, W. H. (1849). On the spontaneous electrical currents observed in the wires of the electric telegraph. Proc. Royal Soc., 139(61), 1849.

2 Kelvin, Lord W. T. (1892). Nature, 47(109).

3 Prescott, G. B. (1866). History, theory, and practice of the electric telegraph. Boston: Ticknor & Fields.

1 Effects of Space Radiation on Contemporary Space‐Based Systems I: Single Event Upsets, Spacecraft Charging, Degradation of Electronics, and Attenuation on Fiber Cabling

Daniel N. Baker1 and Michael Bodeau2

1 Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado, US

2 Northrup Grumman Aerospace Systems, Redondo Beach, California, USA (ret.)

Exposure of space systems to solar energetic particles, galactic cosmic rays, and radiation belt fluxes can cause temporary operational anomalies, damage critical electronics, degrade solar arrays, and blind optical systems such as imagers and star trackers. Moreover, intense solar particle events present a significant radiation hazard for astronauts during the high‐latitude segment of the International Space Station orbit as well as for future human exploration of the Moon and Mars. In addition to such direct effects as spacecraft anomalies, a thorough assessment of the impact of space radiation on present‐day space operations must include the collateral effects of space‐weather‐driven technology failures. For example, space radiation can degrade and, during severe events, completely incapacitate various communication and reconnaissance platforms. A complete picture of the impact of space radiation must include both direct as well as collateral effects of incapacitation on susceptible space structures and systems. It is also imperative that we as a technological society develop a truly operational understanding of space radiation in which the benefits of accurate forecasts are clearly established.

Space systems on which modern society depends mostly operate in the region from altitudes of a few hundred km to ~40,000 km above Earth’s surface. This region is filled with various populations of energetic particles. The fact that the Earth is surrounded by belts of very energetic protons and electrons was the first major discovery of the space age in 1958 (see Van Allen et al., 1958, 1959). From the initial realization that the terrestrial magnetic field could “trap” high‐energy particles, today there is a much more complete understanding of what are now called the Van Allen radiation belts. There has long been awareness of high‐energy solar and galactic cosmic rays as well.

More or less from the beginning of the space age, it was realized that intense populations of penetrating particles could be quite damaging to electronic systems in space (see Gombosi et al., 2017). There also were concerns about spacecraft structural materials and human space travelers (Van Allen, 1966). Thus, from the earliest days, it was realized that the terrestrial space environs were a problem to be reckoned with when it came to flying robotic and human missions in near‐Earth regions. Today it is recognized that space radiation is one of the most pervasive and concerning threats that constitute what we comprehensively term space weather (Baker & Lanzerotti, 2016).

This chapter is intended to provide a brief overview of space radiation sources and their effects. Related impacts are treated in the companion chapter by Bodeau and Baker ( chapter 2, this volume). A second goal of this chapter is to describe from an operational perspective the implications of radiation damage to systems in various parts of the geospace domain. In providing such a brief survey, the goal is to characterize in a succinct way the increasing importance of radiation damage on emerging technological systems.

1.2. OVERVIEW OF SPACE RADIATION PROPERTIES

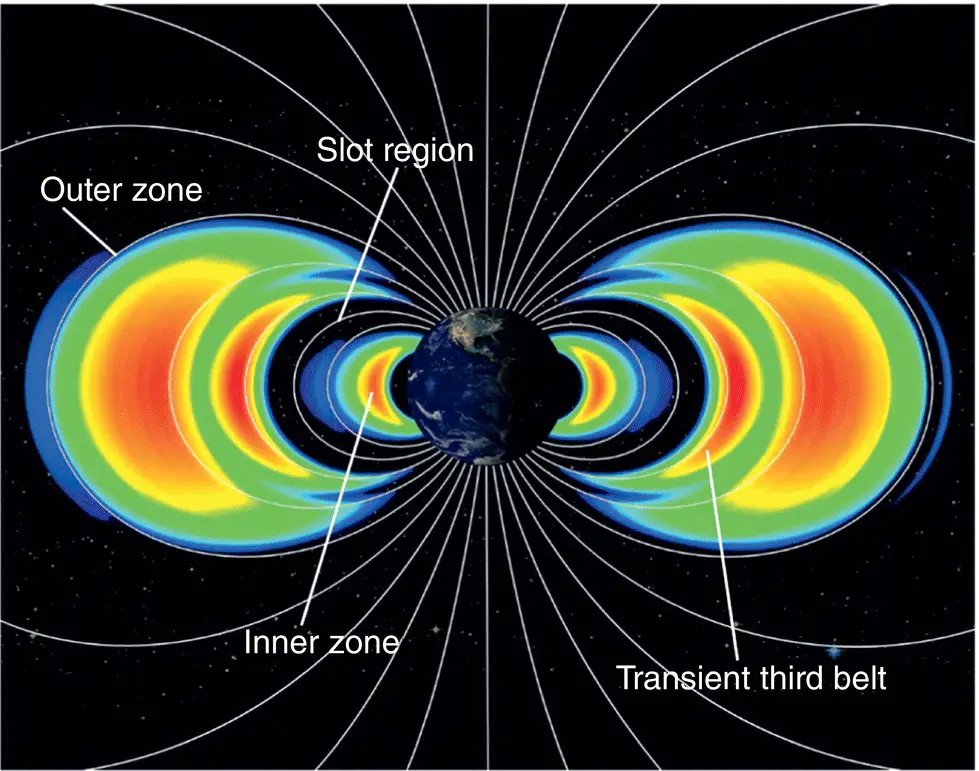

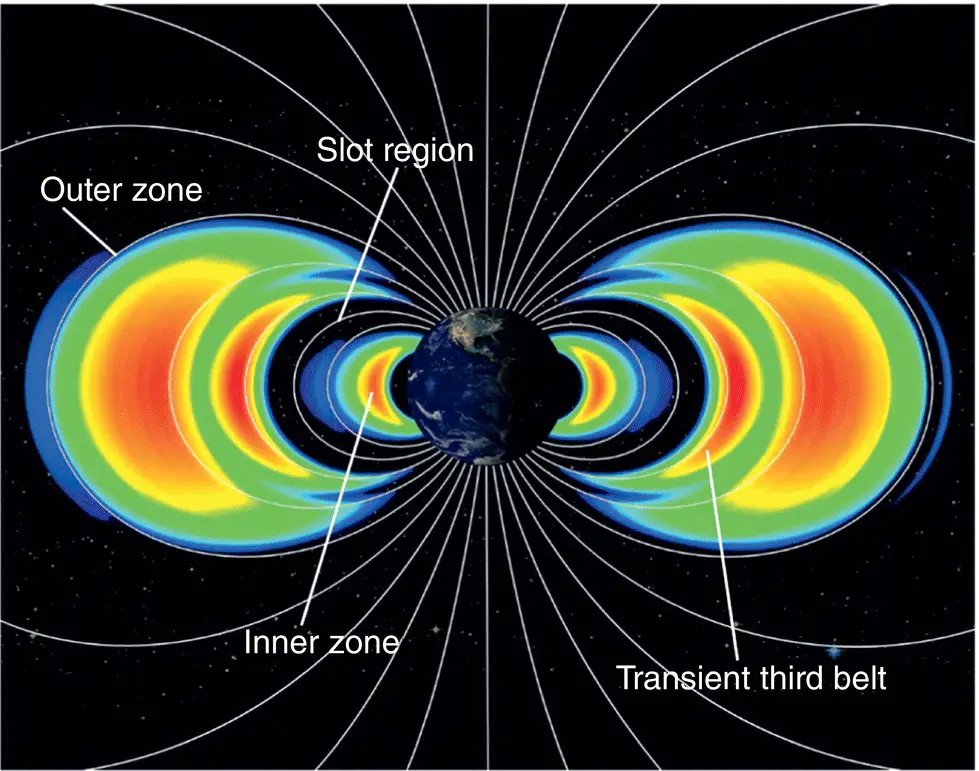

Much of the concern for operational space systems arises from the Earth’s radiation belts. A modern view of the radiation belts derived from the Van Allen Probes observations of Baker et al. (Baker, Kanekal, Hoxie, Henderson, et al., 2013) is shown here as Figure 1.1. Closest to the Earth’s surface is the inner Van Allen belt. This belt extends from just above the dense atmosphere out to an equatorial altitude of about 10,000 km above the Earth’s surface. The inner Van Allen belt is comprised dominantly of very energetic protons (ranging up to multiple GeV energies). Recent results demonstrate that protons with energies from ~10 MeV to ~100 MeV are quite stable in time near the geocentric radial distance of r ~ 1.5R E(Earth radii = 6372 km), at which the inner zone proton fluxes peak. However, an outer “shoulder” of the radial distribution from 1.7 ≤ r ≤ 2.5 R Eshows tremendous temporal variability for protons with E ≤ 60 MeV. These variable proton fluxes are probably due primarily to evolution of trapped solar energetic protons (Selesnick et al., 2014).

Figure 1.1 A modern‐day view of the Earth’s radiation belts as observed by the Van Allen Probes mission.

(Adapted from Baker, Kanekal, Hoxie, Henderson, et al., 2013.)

The inner Van Allen belt also has copious fluxes of low‐and medium‐energy electrons (Fennell et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015) as revealed by Van Allen Probes and other spacecraft data sets (Baker, Kanekal, Hoxie, Batiste, et al., 2013). However, the Van Allen Probes era (September 2012–present) has provided many new discoveries about inner magnetospheric ultrarelativistic electrons with energies E ≳ 5 MeV. In particular, initial results after major storm intervals have shown essentially no detectable prompt ultrarelativistic electron fluxes in the region r ≤ 2.8 R E(Baker et al., 2014). The paucity of very energetic electrons in the inner magnetosphere immediately following major magnetic storms is quite striking (Foster, 2016; Baker et al., 2016) with a fascinating dependence on plasmasphere conditions before the storm and perhaps even on in‐situ radio signals of terrestrial origin (Foster et al., 2016). The consequences of this energetic electron paucity for space radiation effects will be discussed further in this chapter.

Читать дальше