1 ...8 9 10 12 13 14 ...23

Gathering Crime Stats: How Much Crime Is There?

Knowing about every crime that occurs is impossible because many crimes go unreported. For example, a typical cocaine sale involves two willing parties, and neither party is likely to share news of the exchange with the police.

Even with a violent crime, the victim doesn’t always report it. For example, rival gang members involved in a fight aren’t likely to call the police, and victims of domestic violence often don’t report their abuse. (See Chapter 5for more info about why domestic violence victims often keep quiet.) Similarly, rape victims may not want to endure the emotional trauma of making a report to police.

Fraud and property crimes present other challenges. For instance, you probably don’t call the police every time you receive a fraudulent email that asks you to cash a large check for a “Nigerian official.” (See Chapter 6for a discussion of the infamous Nigerian scams.) And you may not even call the police when someone steals your wallet or purse. After all, many people believe that, at least for property crimes, filing a police report simply doesn’t do any good.

Even though many crimes don’t get reported to the police, crime reports are still one of the most important sources for gathering crime stats.

In 2018, the United States had more than 18,000 police agencies, and about 13,000 of them participated in a voluntary program that reports statistics to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). The compiled statistics are published annually in the Uniform Crime Report (UCR). You can access the most recent UCR at the FBI’s website: https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2018/crime-in-the-u.s.-2018 .

The UCR contains information about only certain types of serious crimes, known as Part 1 crimes:

Murder and non-negligent manslaughter

Rape

Robbery

Aggravated assault

Burglary

Larceny-theft

Motor vehicle theft

Arson

Because Part 1 crimes are so serious in nature, experts believe that they’re reported more reliably than less-serious crimes. The UCR purposely excludes crimes that people aren’t likely to report, such as drug offenses or embezzlement, as well as crimes that occur infrequently, such as kidnapping.

But even for crimes that you think a victim would report, the actual report rate is quite low. According to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, only two out of five violent crimes were reported to the police in 2019.

But even for crimes that you think a victim would report, the actual report rate is quite low. According to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, only two out of five violent crimes were reported to the police in 2019.

Besides not receiving reports for every crime, another significant problem with the UCR is that a police agency must pick only the most serious crime from a criminal incident to report to the FBI. In other words, the police can’t report multiple crimes that occurred during a single incident. So, if a man steals a car and then later sets the car ablaze to conceal his first crime, the investigating police agency reports only the arson, not the motor vehicle theft.

This will change in 2021 as the FBI completes its transition to a new reporting methodology — the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS), which is designed to efficiently and accurately gather more information on more crimes from police agencies’ computerized record management systems. The full nature of a multi-crime incident will now be documented.

Despite its problems, the UCR provides a solid, nationwide picture of long-term crime trends and allows for year-to-year comparisons among each of the Part 1 crimes because its problems are generally consistent from year to year.

Despite its problems, the UCR provides a solid, nationwide picture of long-term crime trends and allows for year-to-year comparisons among each of the Part 1 crimes because its problems are generally consistent from year to year.

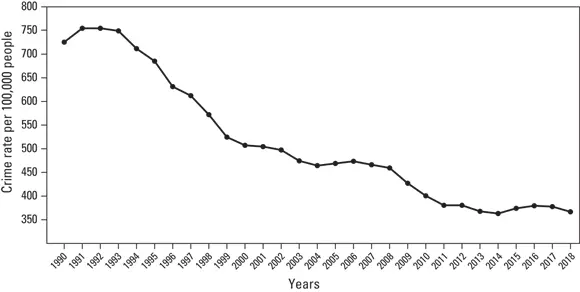

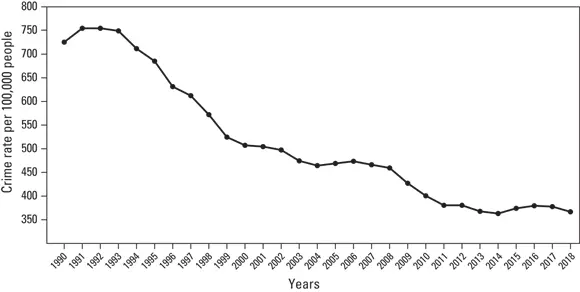

Figure 3-1 compares the overall violent crime rates over the past three decades (provided by the UCR). The numbers reflect how many violent crimes occurred per 100,000 people in the United States.

Tallying the number of arrests

In addition to the number of crime reports, the UCR also collects information on the number of arrests. For these statistics, the UCR looks at not only the Part 1 crimes I mention in the preceding section, but also 21 other crimes, including simple assault and driving under the influence of intoxicants.

Source: Federal Bureau of Investigation

FIGURE 3-1:The U.S. violent crime rate has dropped fairly steadily since 1991.

Obviously, arrest statistics don’t give a full picture of crime. (Arrest doesn’t necessarily mean guilt, and no nationwide statistics show the percentage of arrested persons who are found guilty in state court.) Even so, arrest statistics do help evaluate police effectiveness by showing clearance rates — the percentage of reported crimes that end in arrests. Obviously, the higher the clearance rate, the more effective the police are at catching the bad guys.

Obviously, arrest statistics don’t give a full picture of crime. (Arrest doesn’t necessarily mean guilt, and no nationwide statistics show the percentage of arrested persons who are found guilty in state court.) Even so, arrest statistics do help evaluate police effectiveness by showing clearance rates — the percentage of reported crimes that end in arrests. Obviously, the higher the clearance rate, the more effective the police are at catching the bad guys.

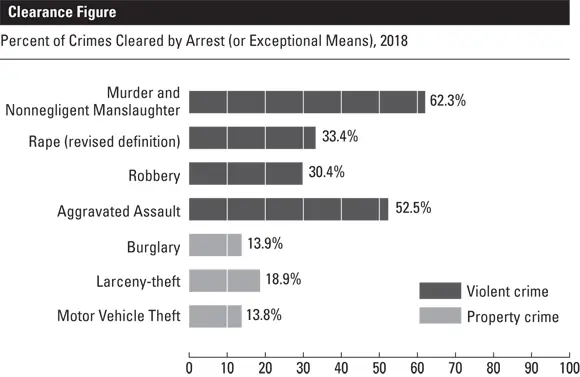

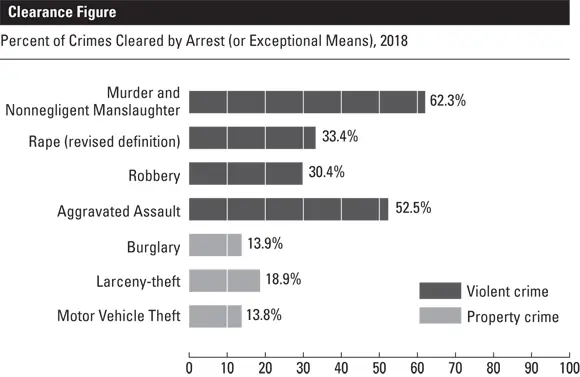

Figure 3-2 shows the 2018 national clearance rates for various crimes.

Source: Federal Bureau of Investigation

FIGURE 3-2:The clearance rates for various crimes in 2018.

You can see that police are much more likely to solve violent crimes than they are to solve property crimes, which is largely a result of the greater resources that police commit to solving violent crimes. Another important factor that leads to the increased clearance rate for violent crime is the fact that violent crimes often leave eyewitnesses who can help identify the perpetrators. In contrast, property crimes often happen in the absence of witnesses.

Arrest statistics provide another tool for evaluating crime rates: Tracking the number of arrests helps track certain trends for crimes that people usually don’t report, such as driving under the influence of intoxicants. Yet, tracking the number of arrests has its shortcomings. For instance, a decrease in the number of arrests for a certain crime may have alternative explanations, including these:

Fewer people are committing the crime.

Police are putting fewer resources into investigating the crime.

Criminals have figured out ways to commit the crime without being caught.

A decrease in a certain crime can have some other explanations, too, so you can’t draw many conclusions from these arrest statistics alone. For example, from 2008 to 2018, reported property crime decreased by 26 percent in the United States. However, it is quite possible that as usage of the Internet has exploded in society, some criminals have stopped stealing purses or committing burglary and instead have gone online where the risk of arrest is very low. An enterprising thief can send emails to millions of targets and only one victim needs to respond for the thief to get his payday. And if you are like me, you don’t call the police every time a Nigerian Prince emails you with an offer to make you rich. (See Chapter 6for a discussion of Internet fraud.)

A decrease in a certain crime can have some other explanations, too, so you can’t draw many conclusions from these arrest statistics alone. For example, from 2008 to 2018, reported property crime decreased by 26 percent in the United States. However, it is quite possible that as usage of the Internet has exploded in society, some criminals have stopped stealing purses or committing burglary and instead have gone online where the risk of arrest is very low. An enterprising thief can send emails to millions of targets and only one victim needs to respond for the thief to get his payday. And if you are like me, you don’t call the police every time a Nigerian Prince emails you with an offer to make you rich. (See Chapter 6for a discussion of Internet fraud.)

Spotlighting unreported crime: Victimization surveys

Читать дальше

But even for crimes that you think a victim would report, the actual report rate is quite low. According to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, only two out of five violent crimes were reported to the police in 2019.

But even for crimes that you think a victim would report, the actual report rate is quite low. According to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, only two out of five violent crimes were reported to the police in 2019.

A decrease in a certain crime can have some other explanations, too, so you can’t draw many conclusions from these arrest statistics alone. For example, from 2008 to 2018, reported property crime decreased by 26 percent in the United States. However, it is quite possible that as usage of the Internet has exploded in society, some criminals have stopped stealing purses or committing burglary and instead have gone online where the risk of arrest is very low. An enterprising thief can send emails to millions of targets and only one victim needs to respond for the thief to get his payday. And if you are like me, you don’t call the police every time a Nigerian Prince emails you with an offer to make you rich. (See Chapter 6for a discussion of Internet fraud.)

A decrease in a certain crime can have some other explanations, too, so you can’t draw many conclusions from these arrest statistics alone. For example, from 2008 to 2018, reported property crime decreased by 26 percent in the United States. However, it is quite possible that as usage of the Internet has exploded in society, some criminals have stopped stealing purses or committing burglary and instead have gone online where the risk of arrest is very low. An enterprising thief can send emails to millions of targets and only one victim needs to respond for the thief to get his payday. And if you are like me, you don’t call the police every time a Nigerian Prince emails you with an offer to make you rich. (See Chapter 6for a discussion of Internet fraud.)