At its core, behavioral finance attempts to understand and explain actual investor and market behaviors versus theories of investor behavior. This idea differs from traditional (or standard) finance, which is based on assumptions of how investors and markets should behave. Investors from around the world who want to create better portfolios have begun to realize that they cannot rely solely on theories or mathematical models to explain individual investor and market behavior. As Professor Statman's quote puts it, standard finance people are modeled as “rational,” whereas behavioral finance people are modeled as “normal.” This can be interpreted to mean that “normal” people may behave irrationally—but the reality is that almost no one behaves perfectly rationally when it comes to finances and dealing with normal people is what this book is all about. We will delve into the topic of the irrational market behavior; however, the focus of the book is on individual investor behavior and how to create portfolios that investors can stick with for the long haul.

Fundamentally, behavioral finance is about understanding how people make decisions, both individually and collectively. By understanding how investors and markets behave, it may be possible to modify or adapt to these behaviors in order to improve economic outcomes. In many instances, knowledge of and integration of behavioral finance may lead to superior results for investors.

We will begin this chapter with a review of the prominent researchers in the field of behavioral finance. We will then review the debate between standard finance and behavioral finance. By doing so, we can establish a common understanding of what we mean when we say behavioral finance, which will in turn permit us to understand the use of this term as it applies directly to the practice of creating YOUR best portfolio.

Why Behavioral Finance Matters

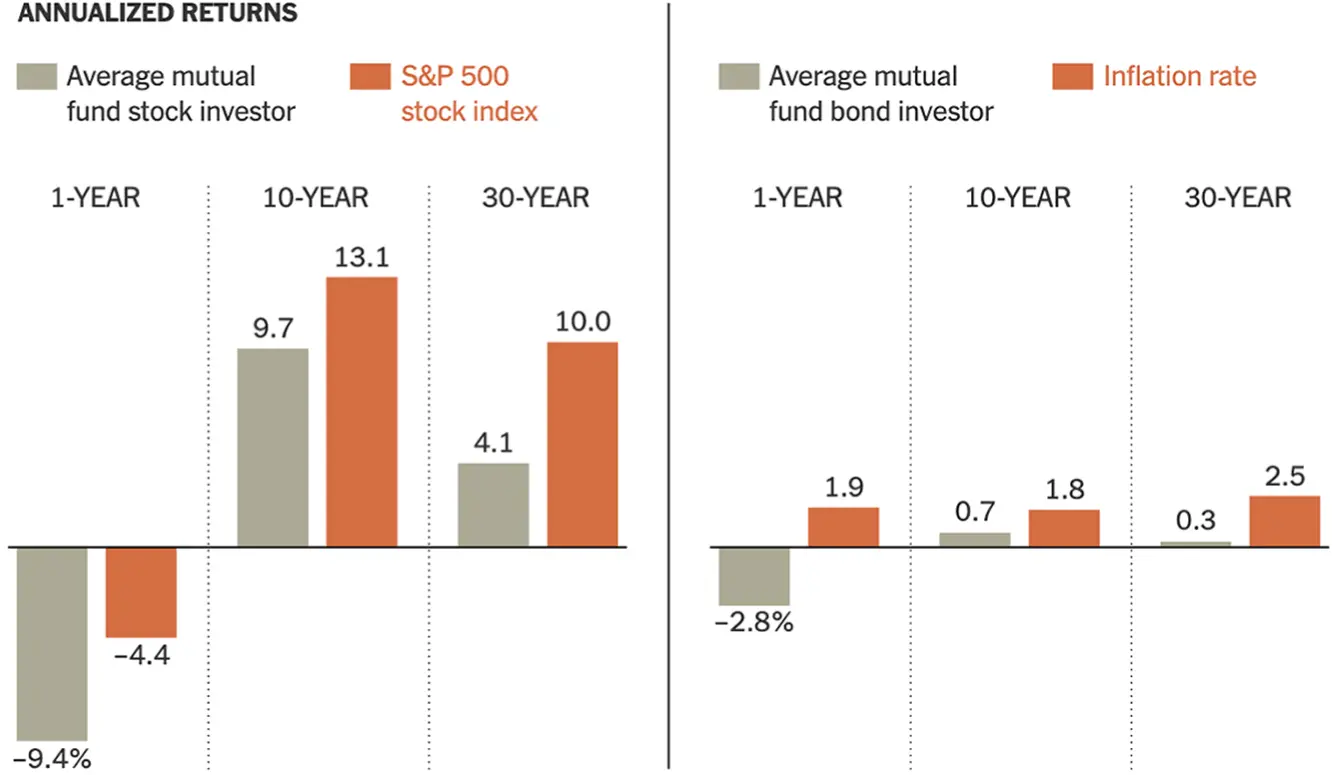

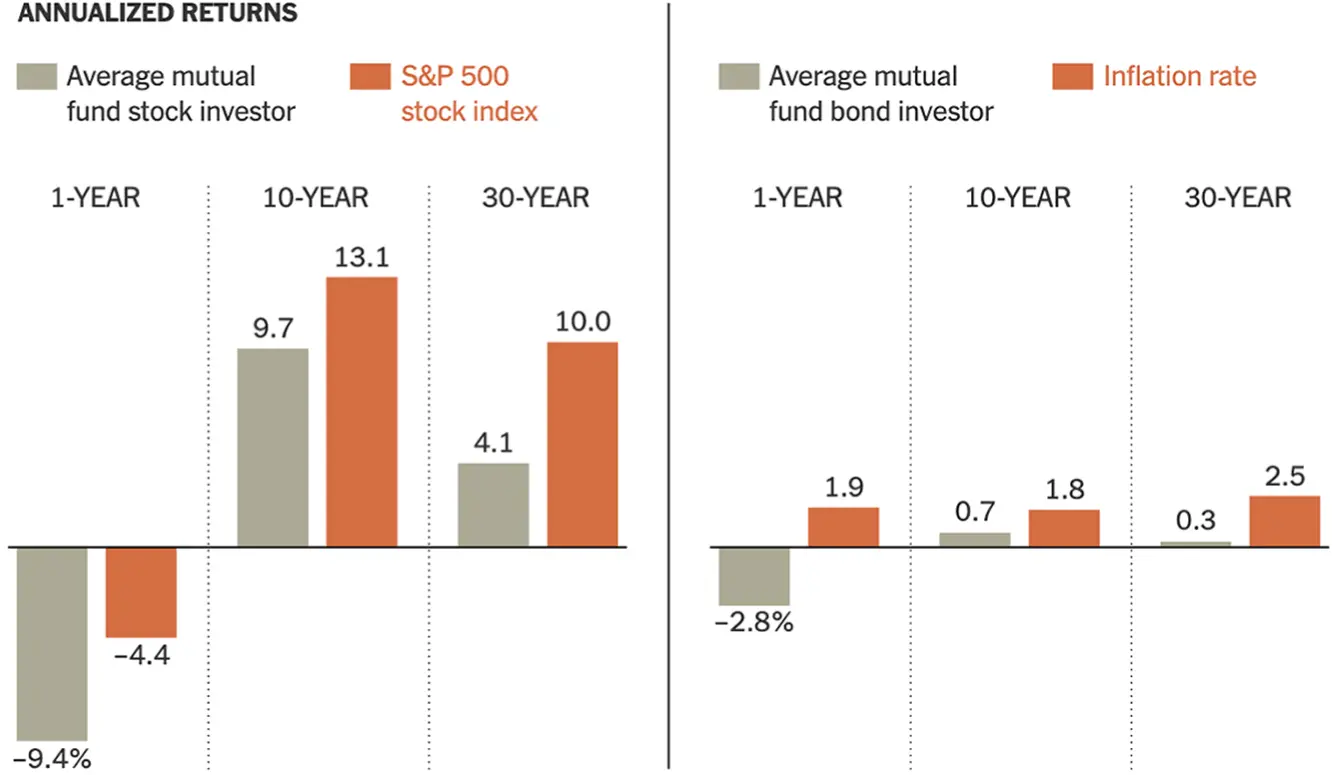

Market research shows that when investors try to protect their portfolios by moving in and out of the market, they limit gains and increase losses. Taking a long-term view is challenging but it is the most rewarding strategy. This is because staying invested helps fuel long-term portfolio appreciation. The primary evidence linking investor behavior to sub-par investment returns is a study done by a firm called DALBAR in Boston every year. This study compares the returns actually earned by the investor to indexed returns and inflation. Investor returns are calculated by DALBAR using the change in total mutual fund assets after excluding sales, redemptions and exchanges. This method of calculation captures realized and unrealized capital gains, dividends, interest, trading costs, sales charges, fees, expenses and any other costs. The most recently available study as of this writing is 2019. 1 That report found that the average investor took some money off the table in early 2018 as the market went up, but was poorly positioned for the second half of the year. The average investor was a net withdrawer of funds in 2018. Poor timing caused a loss of 9.42% on the year compared to an S&P 500 index that lost only 4.38%. Figure 1.1 illustrates the DALBAR data as of the 2019 report. Note the 30-year difference of 6% per annum!

Figure 1.1 Investor Returns from the 2019 DALBAR Report

Source: DALBAR Report, 2019. ©2019, DALBAR, Inc.

Figure 1.2 The Behavioral Finance Gap

The difference between the returns earned by investors holding a given index versus the returns earned by investors who move their money around in an emotional response to market movements is called the “Behavioral Finance Gap.” Figure 1.2 demonstrates this concept. The purpose of this book is to help you minimize this gap so that you can reach your financial goals. MIND THE GAP!

Behavioral Finance: The Big Picture

Behavioral finance has become a very hot topic, generating credence with the rupture of the tech-stock bubble in March of 2000. It was pushed to the forefront of both investors' and advisors' minds with the financial market meltdown of 2008–2009. A variety of confusing terms may arise from a proliferation of topics resembling behavioral finance, at least in name, including: behavioral science, investor psychology, cognitive psychology, behavioral economics, experimental economics, and cognitive science, to name a few. Furthermore, many investor psychology books refer to various aspects of behavioral finance but fail to fully define it. In this section, we will discuss some of the acclaimed authors in the field and review their outstanding work (not an exhaustive list), which will provide a broad overview of the subject. We will then examine the two primary subtopics in behavioral finance: behavioral finance micro and behavioral finance macro. Finally, we will observe the ways in which behavioral finance applies specifically to wealth management.

In Chapter 2we will review a history of behavioral finance. In this section, we will review some key figures in the field who have more recently contributed exceptionally brilliant work to the field of behavioral finance. Most of the people we will review here are active academics, but many of them have also been applying their work to the “real world,” which makes them especially worthy of our attention. While this is clearly not an exhaustive list, the names of the people we will review are: Professor Robert Shiller, Professor Richard Thaler, Professor Meir Statman, Professor Daniel Kahnemann, and Professor Daniel Ariely.

The first prominent figure we will discuss is Yale University Professor Robert Shiller (Figure 1.3). He famously predicted two of the biggest bubbles of all time: the dot-com bubble and the housing bubble. Both times he published an edition of his book Irrational Exuberance , which described and predicted each respective bubble. Perhaps most impressive is the fact that Professor Shiller was one of three people to win the 2013 Nobel Prize in Economics. The theme of the 2013 award was “Trendspotting in Asset Markets,” and the Nobel Committee pointed to Shiller's work in forecasting intermediate-term moves in asset prices. The Nobel Committee was impressed with his work identifying that stock prices fluctuate much more than corporate dividends, and that the ratio of prices to dividends tends to fall when it is high, and to increase when it is low. More recently, Professor Shiller wrote Narrative Economics: How Stories Go Viral and Drive Major Economic Events . 2 In the book he gives a groundbreaking account of how stories help drive economic events—and why financial panics can spread like epidemic viruses.

Figure 1.3 Robert Shiller, Sterling Professor of Economics Yale University and 2013 Recipient of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences

Source: Bengt Nyman/Flickr

Another high-profile behavioral finance researcher, Professor Richard Thaler, PhD (Figure 1.4), is the 2017 recipient of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his contributions to behavioral economics. Thaler studies behavioral economics and finance as well as the psychology of decision-making which lies in the gap between economics and psychology. At the University of Chicago Graduate School of Business, he investigates the implications of relaxing the standard economic assumption that everyone in the economy is rational and selfish; instead he entertains the possibility that some of the agents in the economy are human. He penned a classic commentary with Owen Lamont entitled “Can the Market Add and Subtract? Mispricing in Tech Stock Carve-Outs,” 3 on the general topic of irrational investor behavior set amid the tech bubble. The work relates to 3Com Company's 1999 spin-off of Palm, Inc. and argues that if investor behavior were indeed rational, then 3Com would have maintained a positive market value for a few months after the Palm Pilot spin-off. In actuality, after 3Com distributed shares of Palm Pilot to shareholders in March 2000, Palm Pilot traded at levels exceeding the underlying value of the shares of the original company. “This would not happen in a rational world,” Thaler notes. Professor Thaler is also the author of the book Advances in Behavioral Finance, which was published in 1993.

Читать дальше