A Companion to Chomsky

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «A Companion to Chomsky» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Companion to Chomsky

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Companion to Chomsky: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Companion to Chomsky»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Companion

Companion

A Companion to Chomsky

A Companion to Chomsky — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Companion to Chomsky», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The initially elegant OT model appeared to offer solutions to some longstanding issues, and introduced a set of different problems—a normal situation in discussion of incommensurable theories in any scientific field. However, it quickly became apparent that the innate component of phonology in OT terms was implausibly rich, requiring an extensional characterisation of a large set of constraints as part of innate endowment. More recently, the issue of nativism is just ignored in most OT literature, but has to be understood as tacitly rejected given the specificity of the constraints posited, such as “Assign one violation for each contrast between N and NC in which NC does not have an oral release that belongs to category of 4 or larger along the RELscale,” which is an actually proposed constraint in a paper in the journal Phonology (Stanton 2019). In addition, various scholars posit constraints that are not just specific to one language, but to the realization of one morpheme in a particular language, such as the ALIGN‐ um ‐L markedness constraint that refers to the Tagalog morpheme /um/ (Kager 1999, p. 122).

Outside of the OT literature, we find anti‐nativist titles such as The emergence of distinctive features (Mielke 2008) and “Phonology without universal grammar” (Archangeli and Pulleyblank 2015). How is it possible that Chomsky's stature in phonology is universally recognized by the phonological community, as is his development of the idea of Universal Grammar, and yet, so much current work, even by his former students, is anti‐nativist, anti‐UG? We think we have the answer, but first let's document (with added boldface) the not uncommon denial of nativism via the denial of the argument of the poverty of the stimulus (APoS) in the phonological literature.

Perhaps it is not surprising that a psychologist like Peter MacNeilage rejects the APoS:

Example (6.1)Peter MacNeilage, The origin of speech (2008: 41):

however much poverty of the stimulusexists for language in general, there is none of itin the domain of the structure of words, the unit of communication I am most concerned with. Infants hear all the wordsthey expect to produce. Thus, the main proving ground for UG does not include phonology.

This anti‐nativist perspective is also implicitly anti‐internalist since it suggests that words are out there for children to hear, a view at odds with the generative program as understood by, say, a syntactician like Howard Lasnik (2000, p. 3):

The list of behaviors of which knowledge of language purportedly consists has to rely on notions like “utterance” and “word.” But what is a word? What is an utterance? These notions are already quite abstract. Even more abstract is the notion “sentence.” Chomsky has been and continues to be criticized for positing such abstract notions as transformations and structures, but the big leap is what everyone takes for granted. It's widely assumed that the big step is going from sentence to transformation, but this in fact isn't a significant leap. The big step is going from “noise” to “word.”

MacNeilage's view also has an unfortunate English‐centred perspective on words. In an agglutinative language like Turkish, a given root can appear in hundreds or thousands of words, such as the root ev “house” in the noun evlerimizdekilerinki meaning “the one belonging to the ones in our houses” (Hankamer 1989, p. 397). Children clearly do not hear all the words that they can produce.

Phonologist Jeff Mielke's work arguing against an innate set of phonological features also rejects APoS:

Example (6.2)Mielke (2008), The Emergence of Distinctive Features

“Many of the arguments for UG in other domains do not hold for phonology. For example, there is little evidence of a learnability problem in phonology.” [p. 33]

[Most of the evidence for] “UG is not related to phonology, and phonology has more of a guilt‐by‐association status with respect to innateness.” [p. 34]

Although Mielke dedicates a whole monograph to arguing that features can be learned, he never addresses logical arguments against such a view presented by Fodor (1980) and others, or the clear assertion by Chomsky and Halle (1965) that “one does not ‘construct features from scratch for each language’” in a response to the American Structuralist linguist Fred Householder (1965).

In a discussion of Chomsky's legacy, it is most relevant to note the divergent perspectives on such matters of phonologists who have worked in the generative tradition:

Example (6.3)Archangeli and Pulleyblank (2015) “Phonology without universal grammar”

“See Mielke [2004/8] on why features cannot be innately defined, but must be learned”

“[Children face] the challenge of isolating specific sounds from the sound stream”

“the predictions of [Emergent Grammar] fit the data better than do the predictions of UG.”

Example 6.4Blevins (2003, p. 235), Evolutionary Phonology

“ Within the domain of sounds, there is no poverty of the stimulus. [I offer] general arguments against the ‘poverty of stimulus’ in phonology, …[there is no evidence that] regular phonological alternations cannot be acquired on the basis of generalizations gleaned directly from auditory input.”

These passages clearly locate segments in the auditory input, the “sound stream,” and thus reject the radical rationalist‐internalist perspective of Chomskyan phonology alluded to above, simply expressed by Hammarberg (1976, 354): “[I]t should be perfectly obvious by now that segments do not exist outside the human mind.” Scholars denying a poverty of the stimulus problem for phonology fail to recognize the well‐established difficulty of defining invariant acoustic correlates of segments, a challenge known as the Problem of the Lack of Invariance, which is discussed insightfully by philosopher Irene Appelbaum (1996).

Finally, here is yet another phonologist, author of a popular text and co‐editor of a philosophically oriented volume on phonological knowledge (Burton‐Roberts et al. 2000) rejecting phonological internalism and nativism in one breath:

Example (6.5)Carr (2006), “Universal grammar and syntax/phonology parallelisms”

“Phonological objects and relations are internalisable: there is no poverty of the stimulus argument in phonology. No phonological knowledge is given by UG.”

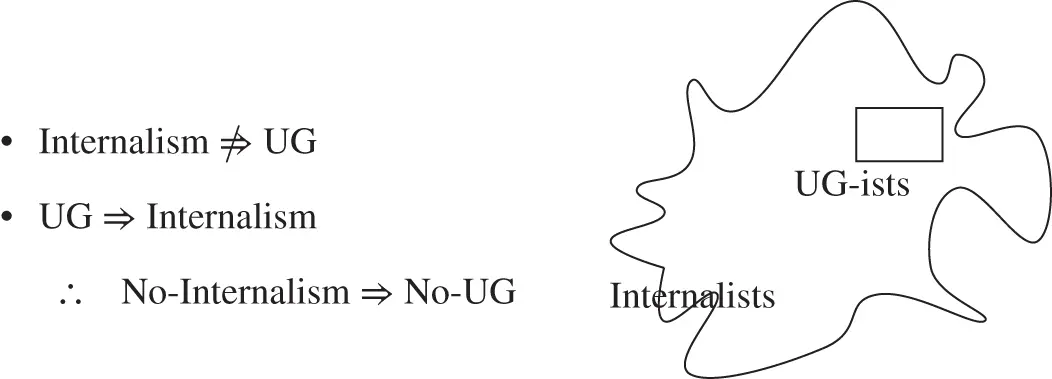

Carr's quotation makes clear the logical relationship between internalism and nativism, and helps us to explain the rejection of nativism as a logical consequence of a failure to appreciate internalism: if phonology is internalisable, it need not be innate. A non‐Chomskyan linguist or psychologist studies the mind, and so is an internalist, but he or she may very well deny any interesting domain‐specific innate knowledge—think of your average connectionist. So, internalism definitely does not imply nativism. However, there is a valid implication in the other direction: Universal Grammar is a claim of innate knowledge, so a nativist in cognitive science has to be an internalist. By contraposition we know that if “nativism implies internalism” is true, then “Not‐internalism implies Not‐nativism” is also true. And that's the problem: For many phonologists, it is logically impossible that they be nativists, because they are not internalists.

Example (6.6)The relationship between internalism and nativism:

So, given the rejection of the internalist legacy of SPE , the nativist legacy stands no chance. This anti‐internalism is clear from claims in phonology, phonological acquisition, and speech perception literature that features, segments, alternations, patterns and so on are in the signal, to be found by the listener / learner. We know, however, that just as a Necker cube is not discovered by our visual faculty, but instead is invented by the mind each time it is perceived or imagined (Marr 1982), in the same way, the mind constructs phonological representations out of a limited set of innately available resources such as features. We even see this happening when we interpret the sounds of a parrot or Hoover the “talking” seal as speech—the words and segments we “hear” are definitely not out in the world.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Companion to Chomsky»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Companion to Chomsky» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Companion to Chomsky» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.