CLASSIFICATION FOR ROOT PROXIMITY

Vermylen et al proposed a classification system for root proximity to indicate location (apical, middle, and coronal third) and severity based on modification of the ruler used by Schei et al 123and findings from Heins and Wieder 120as depicted in Table 5-9. 113

TABLE 5-9 Classification for root proximity by Vermylen et al 113

| Location |

A |

Apical third of the root |

| B |

Intervening (middle) third of the root |

| C |

Coronal third of the root |

| Severity |

1 |

> 0.5 and ≤ 0.8 mm. A small amount of cancellous bone is present between the adjacent roots. |

| 2 |

> 0.3 and ≤ 0.5 mm. Only cortical and connective tissue attachment is present between the adjacent roots. |

| 3 |

≤ 0.3 mm. Only connective tissue attachment is present between the adjacent roots. |

Root Surface Anomalies

INTERMEDIATE BIFURCATIONAL RIDGE

Intermediate bifurcational ridge (IBR)is defined as a distinct ridge running across the bifurcation in a mesiodistal direction. 10It originates from the mesial surface of the distal root at about 2 mm from the height of the furcation area and ends high up on the distal surface of the mesial root by merging within the root concavity. 10Histologic evaluation of IBRs has shown that these developmental anomalies are formed mostly by dentin but also contained cementum. 10

Everett et al reported that among 328 extracted mandibular first molars, the prevalence of IBRs was 73%. 10This finding was confirmed by two other studies that revealed a presence of IBRs in 70% and 76.8% of extracted first molars. 68,124Moreover, Hou and Tsai found that IBRs are highly associated with CEPs (63.2%) and Class III furcations (25.3%). 55

Hou and Tsai introduced a grading system for IBRs using an electronic digital caliper to calculate dimensions as less than 1 × 1 mm, between 1 × 1 mm and 2 × 2 mm, and 2 × 2 mm or greater as Grades I, II, and III, respectively. 55It is important to bear in mind that when IBRs are present in furcation defects, these may predispose to further attachment loss by hindering the patient’s plaque control and the clinician’s ability for proper mechanical instrumentation during active and/or supportive therapy.

The palatal grooveis a developmental, anomalous groove usually found on the palatal aspect of maxillary central and lateral incisors. It is also known as palatogingival groove or palatoradicular groove . 1These structures are considered a funnel-like anomaly predisposing to the accumulation of biofilm and calculus formation. 125–132The prevalence of this condition ranges from 1.9% to 18%, affecting primarily maxillary lateral incisors and central incisors with a possible predilection for individuals of Asian descent ( Table 5-10). 70,127,128,131,133–135

TABLE 5-10 Prevalence of palatoradicular grooves

| Authors |

Population |

Affected teeth |

Prevalence |

| Everett and Kramer 133 |

American |

Lateral incisors |

1.9% |

| Gher and Vernino 70 |

American |

Lateral incisors |

3% |

| Withers 131 |

American |

Lateral and central incisors |

Overall: 2.33%Bilateral: 0.75%Lateral incisors: 4.4%Central incisors: 0.28% |

| Kogon 127 |

Canadian |

Lateral and central incisors |

4.6% |

| Bačić et al 128 |

Croatian |

Lateral and central incisors |

1.01% |

| Hou and Tsai 134 |

Taiwanese |

Lateral and central incisors |

18.06% |

| Albaricci et al 135 |

Brazilian |

Lateral and central incisors |

Overall: 9.3%Lateral incisors: 11.1%Central incisors: 7% |

Embryologically, these anomalies arise as a mild form of invagination from the folding of the enamel epithelium and are closely related to dens in dente. 133As a result, a clinically detectable hollow groove can be observed proceeding apically for a variable distance along the length of the root. Hou and Tsai noted an increased predilection of these grooves for midpalatal areas (42.5%) when compared with mesial (27.4%) and distal (30.1%) surfaces. 134Moreover, it has been reported that 58% of the grooves extended more than 5 mm from the CEJ, 127whereas 8.6% can reach the root apex. 135Radiographically, these might be detected as radiolucent, parapulpal lines representing a radicular extension of the palatal groove. 126,130

Localized forms of periodontitis have also been associated with the presence of palatoradicular grooves. 128,130–132Teeth with palatoradicular grooves revealed worse periodontal health as evidenced by higher gingival index, plaque index, and periodontal disease index scores when compared to teeth without grooves. 131Similarly, Bačić et al reported significantly greater probing depths (mean: 8.8 mm) at sites with palatoradicular grooves among periodontal patients. 128Hou and Tsai also noted deeper pocket depths when palatoradicular grooves were present. 134

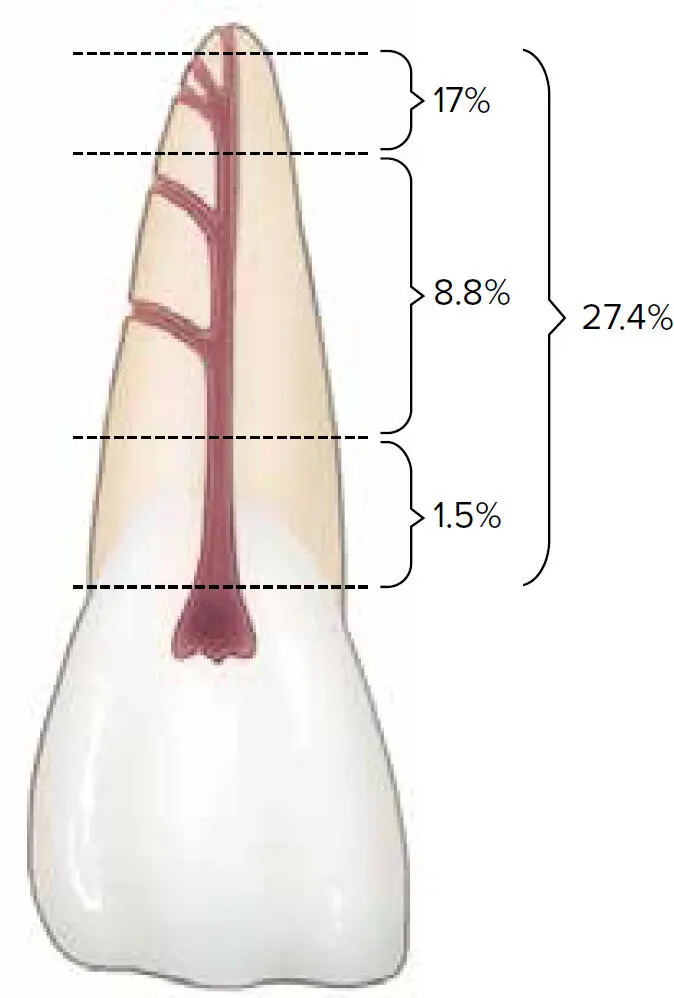

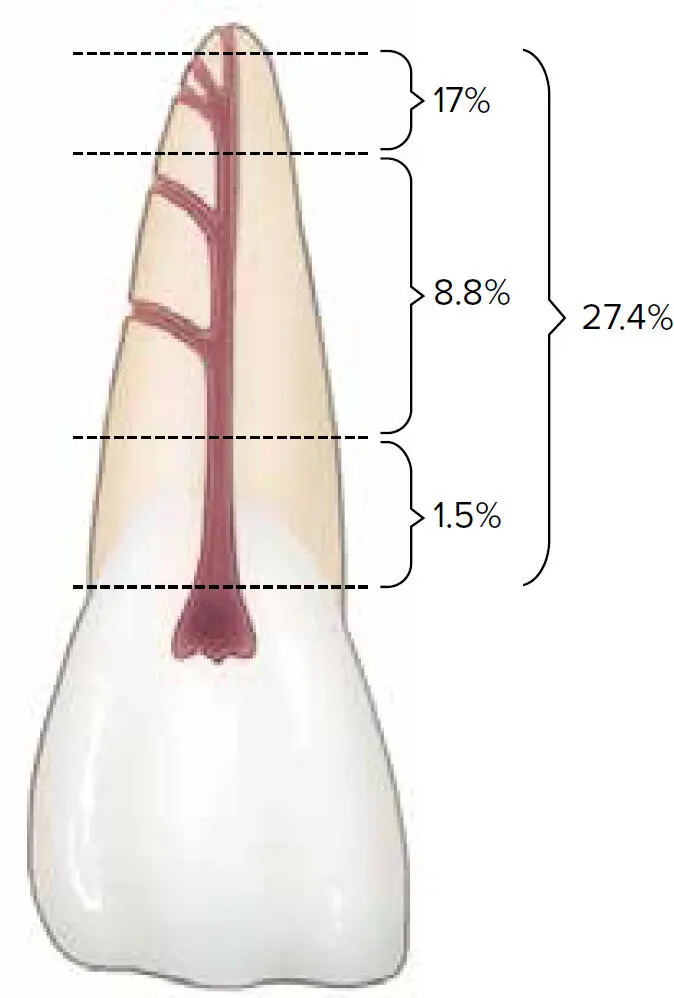

Accessory root canals are considered a lateral branch of the main root canal most often found in the apical half of the roots and in furcation areas. 1The formation of these accessory root canals has been labeled as lines of weakness and attributed to a defect in the HERS during the development of the root at the site of a larger vessel. 136,137The size of the foramina of these canals might range between 4 and 250 μm, and the canals are more numerous and larger in diameter among maxillary molars than mandibular molars. 138Early studies reported the presence of an accessory apical artery entering the tooth via the periodontal ligament. 139Kramer demonstrated large blood vessels within the furcation region running through the radicular dentin to supply one root canal vascular system. 140At times, these vessels appeared to contribute more to the root canal vascular supply than those entering the apical foramen. 140

The terminology used to describe root canal ramifications is diverse. De Deus identified different types of root canals based on their location (eg, apex, body, and coronal third) as accessory , secondary , and lateral canals. 141Some authors have referred to them as furcation canals when they are exclusively located at the furcation region. 142,143

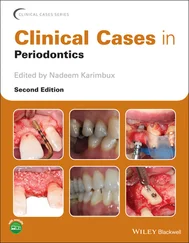

Vertucci and Williams reported a 46% prevalence of accessory canals in a study of 100 mandibular molars. 143The authors also established an association between their occurrence and the site of origin (pulp chamber or root surface) and the possibility to have multiple accessory canals. Conversely, Kirkham found that 23% of the teeth had accessory canals and reported an association with periodontal defects in 2% of the cases. 144In a similar manner, Gutmann reported a prevalence of 28.4% of accessory canals at furcation regions from maxillary and mandibular molars. 142Finally, De Deus used a sample of 1,140 teeth and reported an overall (27.4%) and a site-specific prevalence (apex: 17%; body: 8.8%; and base: 1.6% of the root) 141(Fig 5-4).

Fig 5-4 Prevalence of accessory canals.

Overall, a large variation (17% to 92.5%) for the prevalence of accessory canals has been observed. This wide range can potentially be attributed to multiple factors. 124,141–149It is important to bear in mind that these canals are encased by dentin, and a calcification process might cause the number of canals to diminish with age. 150Also, subtle differences can be associated with the tooth type, 143,145,146the reason for extraction (eg, caries, periodontal disease, endodontic failure), deposition of cementum, 147and processing methods (eg, drying, vulcanizing). 151

Читать дальше