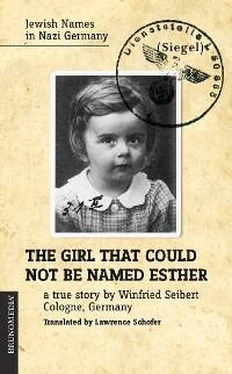

Winfried Seibert - The girl that could not be named Esther

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Winfried Seibert - The girl that could not be named Esther» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The girl that could not be named Esther

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

The girl that could not be named Esther: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The girl that could not be named Esther»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A true story about jewish names in Nazi-Germany 1938.

“You can’t name her Esther. And you can’t name him Joshua. These are not truly Germanic names.” – German bureaucratic and judicial decisions in 1938.

Residents of English-speaking countries are in the main accustomed to naming their children with any name they want. Other countries are not so permissive, requiring an approval for registration of names. In Nazi Germany, this ordinarily innocuous law became part of the racist arsenal of the regime, a regime that had enthusiastic adherents all through the bureaucracy and the judicial system.

An article in a law journal caught the eye of attorney Winfried Seibert, born in 1938, and he set off on an ingenious search of German history in the Nazi period, looking for the girl “who couldn’t be named Esther.”

A determined pastor in a small town in the Ruhr Valley demanded in 1938 that his daughter’s name be registered as “Esther.” He ran into bureaucratic opposition and fought his case through the courts all the way to the Supreme Court for Civil Matters in Berlin. He lost. So did a park ranger, who wanted to perpetuate the family name “Cuno Joshua.”

What the author has done in this book resembles the unfolding of a mystery story. Who was this minister, identified only as the “Minister L. from the town of W.”? Why was he so hard-headed? Who were these local officials who so adamantly defended the “purity” of German names? What kind of justice system enforced these laws?

The author started with “L. from the town of W.” With some ingenious detective work, he found the town, the likely person, and then even the son of that courageous pastor – though not the daughter “Esther.”

This book is a very close examination of the people involved – the minister, the bureaucrats, and especially the judges. The author reconstructs the life stories of the three judges who sat on the Supreme Court. Interestingly, the judges found that Esther was a “criminal prostitute of the Jewish race,” while Ruth, a name that one might expect to be condemned in the same way, was allowed as a “Germanified” name. One of the judges had a daughter named Ruth.

The book contains a fascinating reconstruction of the German justice system based on the use of this single case. Through the use of this case, the readers sees the Nazi justice system and Germany itself through its pogroms and then into the war period itself. Instead of relying on masses of data and statistical compilations, this book energetically and passionately moves through the daily activities of Nazi justice. The unfolding of these items is a gripping tale that caught the attention of tens of thousands of German book-buyers and of reviewers throughout the German language press in Germany and in Israel (originally published in 1996).

And what of little Esther, who was denied her name so that she would not be embarrassed when she would be taken into the League of German Girls? Named “Elisabeth” by the officials, the author found notice of her baptism in 1946 as Esther. Unhappily, the search showed that the little girl had died of a childhood disease at age 2 ½, but her father had preserved her memory by “renaming” her after the defeat of the Nazis. The pastor himself served in the German army, but continued to incur the wrath of his superiors for his sermons, which used ambiguous language to denigrate the German leadership.