There are different laws and regulations in each country that may impact dental practice and these are present to ensure the safety of patient care. This may involve having evidence of competency for the intended treatment, and infection control, workplace safety, continuing education requirements, and materials that can be used in practice.

It is important to only provide treatment for which you have appropriate training within your scope of practice. A clinician should be able to demonstrate the experience and education undertaken, completing a logbook of all continuing professional development attended. Furthermore, a clinician will need to record all aspects of the examination, assessment, and treatment, as well as consent attained, in a neat and legible manner. With the advent of digital records this has improved record keeping, helping legibility and avoiding any deterioration in radiographic records, such as happened in the past with dental film. The increasing use of digital impressions and scanning has taken away the onerous task of storing physical models, allowing data storage in the cloud and giving the ability to access the virtual models relatively easily.

Informed consent is permission granted in full knowledge of the possible consequences, typically that which is given by a patient to a doctor for treatment with knowledge of the possible risks and benefits. As implant treatment is an elective treatment it should involve a two‐way communication between patient and clinician that provides an unbiased and objective view of the treatment. This includes the intended outcome, alternatives to treatment, and an understanding of treatment difficulty and risk of complications or failure. It is customary that this is conveyed to the patient verbally; many clinicians also provide informed consent forms and other literature that clearly document treatment for patients.

4.2 Procedures

4.2.1 Dental Records

Dental records are important medical and legal records documenting all aspects of treatment along with information on what biomaterials, hardware, and implant systems were used. They should be complete, accurate, and legible. If a complaint is encountered in relation to treatment the records are your only defence if the patient proceeds with legal action.

The records should include:

Reason for attendance (chief complaint)

Medical history

Dental history

Social and family history

Clinical assessment – extra‐oral and intra‐oral examination

Diagnostic records, including photographs, radiographs, study models, diagnostic wax‐up, etc.

Surgical phase of treatment:Medications administered or prescribed, including local anaesthetics, sedation, and antibiotics, with their dosageSurgical flap design and wound closure, including suture size and typeImplant components with type of implant system and the lot numbersBiomaterial usage, including bone graft, membranes, tacksPrimary stability and insertion torque, implant stability quotient (ISQ) valuesPost‐operative instructions and management

Prosthodontic phase:Implant integration assessmentImpression technique and materialsShade selection and photographyLaboratory prescriptionInsertion of prosthesis with components used, abutment screw torque, type of retention (screw/cement) and screw access closureRadiographs to document baseline radiographsOral hygiene instruction and continuing care frequency

Continuing care:Assess prosthesis integrityAssess occlusion Assess peri‐implant tissue health with probing depths and bleeding on probingRadiographs to monitor bone levels.

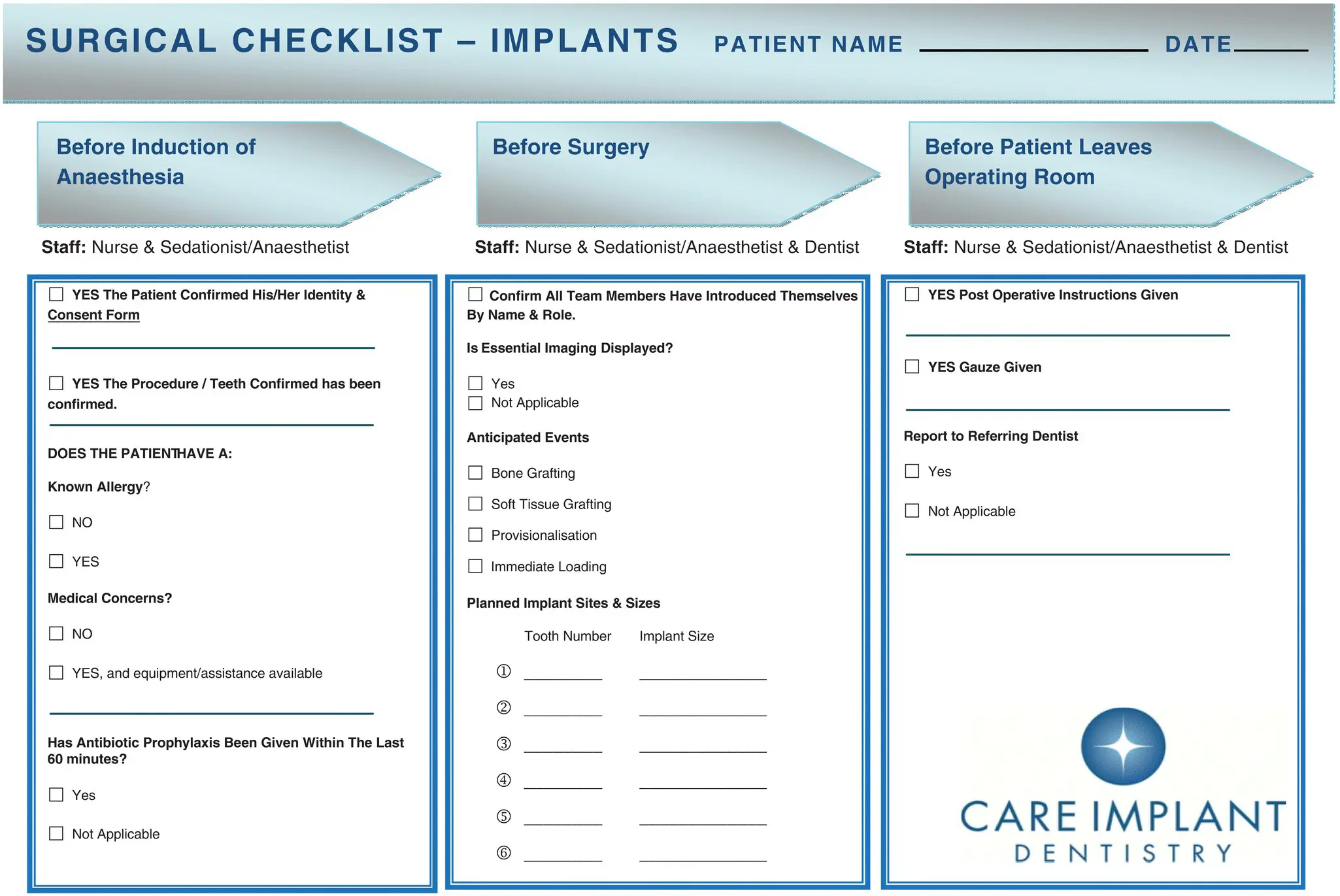

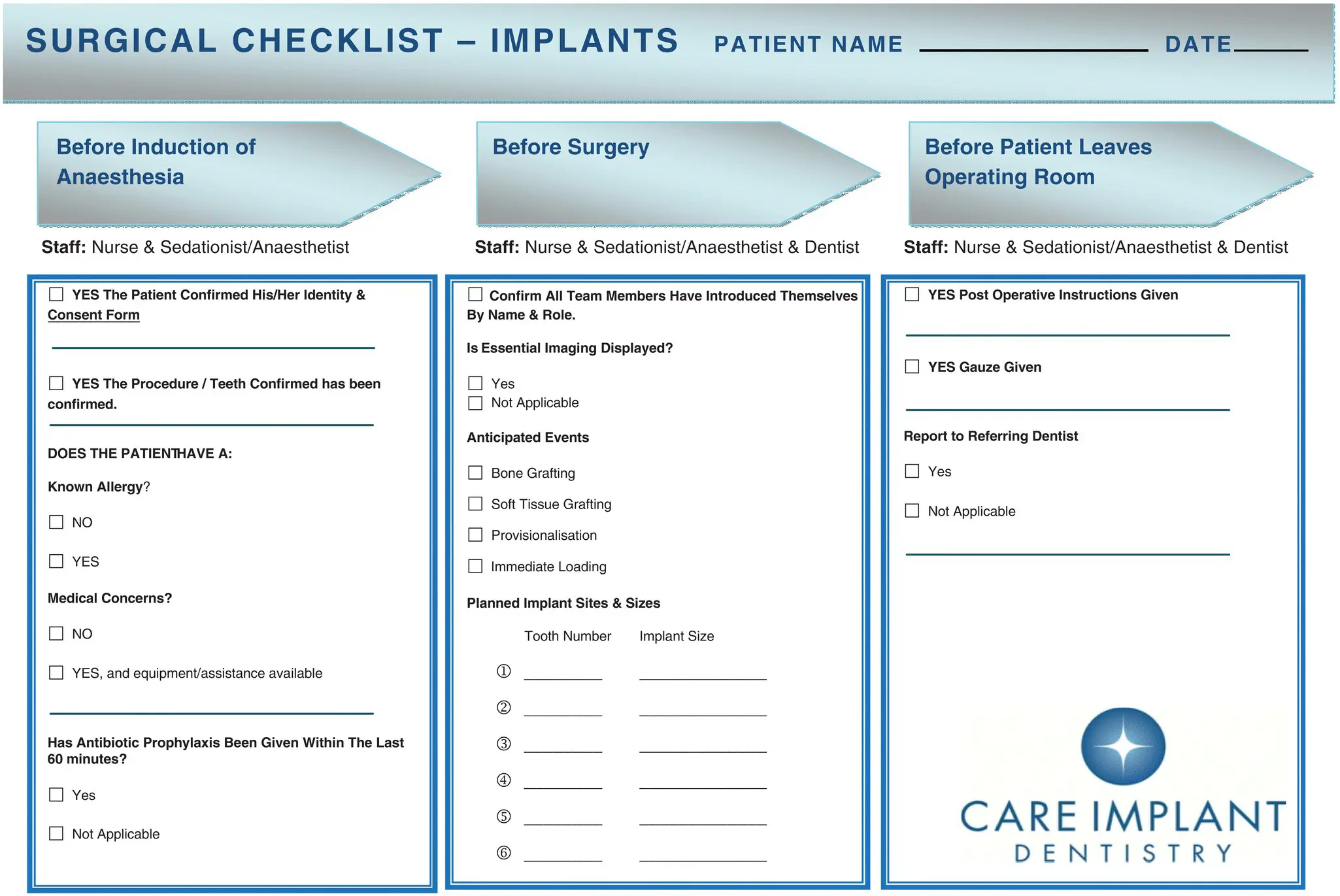

Checklists: A checklist is a type of aid used to reduce failure by compensating for potential limits of human memory and attention ( Figure 4.1). It helps to ensure consistency and completeness in carrying out a task. It is good practice to have a checklist summary to provide consistency of care because clinicians and their teams often lull themselves into skipping steps after performing procedures multiple times as it becomes familiar and repetitive. A checklist may aid in protecting against such failure and remind the team of the steps and procedures required. The author likes to work with checklists both at consultation and treatment procedures. At the time of consultation a checklist ensures everything is explained to the patient, with written documentation of what was communicated. Moreover, this is carried through into clinical practice, with checklists on what is required for procedures, as well as a pre‐surgical checklist to confirm that patients are ready for their surgical procedure. An example of what may be included in this pre‐surgical checklist includes:Patient confirmation of procedureMedical history update, including any medications taken and allergiesPre‐operative antibiotics and pain medicationsPlanned implant and components in stockAnticipated events, e.g. soft tissue or hard tissue grafting, provisionalisation, and immediate loading.

Figure 4.1 Example of a surgical checklist. Source: Care Implant Dentistry.

Make sure you have explained all treatment options, even those you may not consider within your area of expertise. This should include all advantages and disadvantages as well as any risks of treatment.

Be prepared to refer the patient if the treatment is beyond your area of expertise or experience.

It is good practice to conduct a consultation with your patient and provide a written treatment plan. Time must be allowed for the patient to have opportunity to discuss and ask any questions pertaining to their intended treatment.

The patient needs to be informed of all likely costs and time for treatment. This should also include any future costs of treatment including any maintenance required.

1 1 Banerji, S., Mehta, S., and Ho, C. (2017). Practical Procedures in Aesthetic Dentistry, 3–5. Chichester: Wiley.

5 Considerations for Implant Placement: Effects of Tooth Loss

Kyle D. Hogg

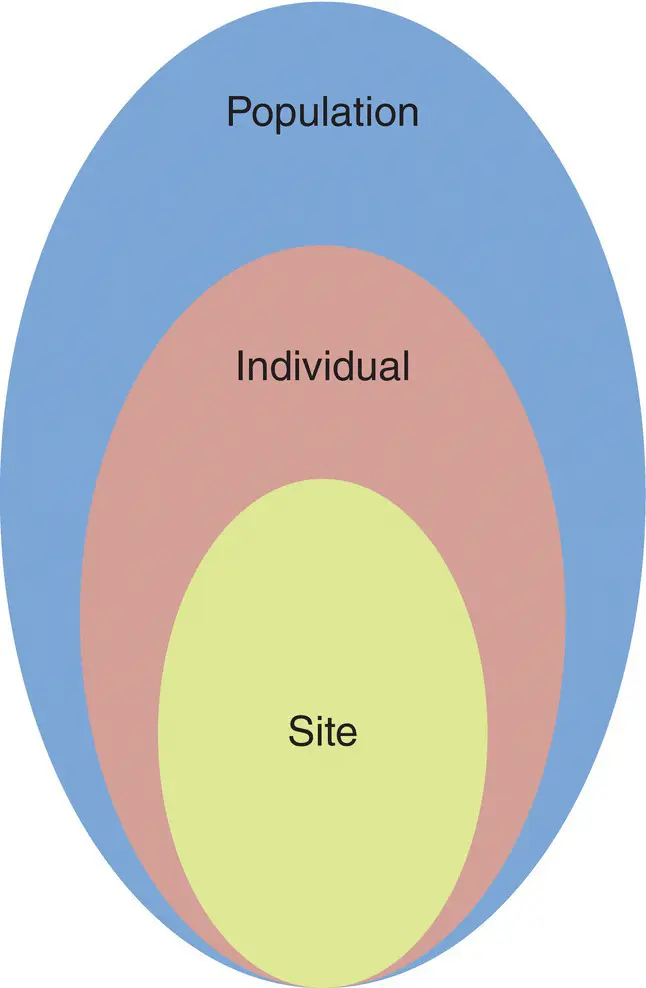

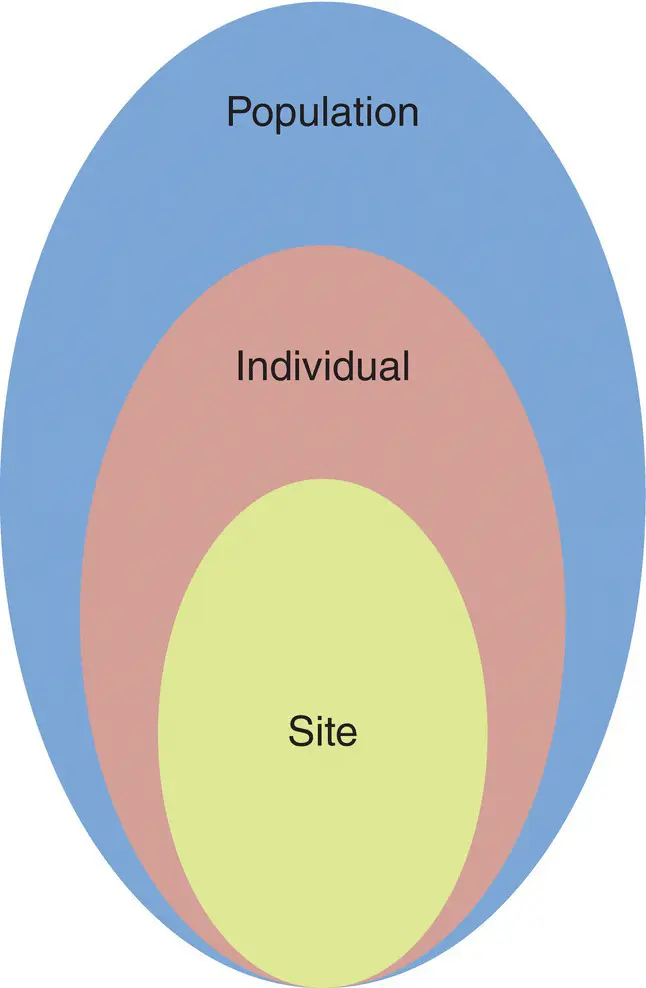

Tooth extractions are among the most commonly performed dental procedures worldwide, with the wound created in the form of the extraction socket typically healing in a routine and uneventful manner. The effects of tooth loss in humans can perhaps best be understood when viewed at three related levels, namely: local site effects, effects on the individual, and effects on the population ( Figure 5.1). The effects of tooth loss on the site, individual, and population levels have a profound influence on clinical decision‐making and treatment strategies. While the site of the extraction heals in a predictable manner, the impact of the loss of the tooth on the individual can be quite variable. There is considerable evidence relating tooth loss to diminished oral health‐related quality of life at the population level, and in addition a more heterogeneous experience can be found at the individual level [1].

Figure 5.1 Tripartite effect of tooth loss.

5.1.1 Local Site Effects of Tooth Loss

The loss of a tooth or teeth initiates a dynamic sequence of events resulting in marked changes to the surrounding alveolar process of the jaw, largely a tooth‐dependent structure [2], while causing little change to the underlying basal bone. The gradual pattern of bone resorption in the mandible is depicted in Figure 5.2, which shows the contour changes from the dentate state (image on lower left) to advanced alveolar bone loss (image on upper right).

Читать дальше