I follow their lead, pump my gas and return to collect my credit card. This time, a young man offers for me to go ahead of him. I decline but he insists with such firmness that I can only say thank you and accept. While waiting for the clerk to process my card, I turn around and start a casual conversation with this man. I talk about the weather; yesterday was unbearably hot and today is a breezy spring day that feels perfect. He agrees. I make a comment about the unpredictability of the weather that gets a laugh. He has a beautiful smile and for a moment I make eye contact. And then his face closes and I know to return to my business. I realize much too late that, in some communities, survival can depend on learning to see nothing and say nothing. That in some places in the country, eye contact might get you killed. Is this where I am? If so, it is all the more amazing that ordinary acts of kindness seep through in daily interactions. I collect my card receipt and leave.

Signs of an informal economy are everywhere – in the particular presence of young men on street corners, in the sparkle of polished rims on new cars, and in the very serious young men scanning the environment as they drive slowly past. I wonder if the gas station, or the area around it, is some sort of drop point. As I type up my notes, I wonder if I should have used cash. Could my card have been skimmed while I pumped? The corrosive power of doubt seeps in as I reflect. My card was not skimmed, and it is worth noting that when it has been in the past it was always in wealthier, whiter places that I had not learned to see as dangerous. This is not to minimize or deny that violence that has come to characterize the communities around 106th Avenue, but to acknowledge the humanity of people living there and the prejudice that outsiders bring to it – intentionally or not.

Vanessa Torres is one of the more than 15,000 people who live in the Deep East. Vanessa grew up with her parents and four siblings in a two-bedroom apartment they rented for about $1,700 a month. As the oldest of the five children, she has had a lot of responsibility in the family. She began translating for her parents at age eight, and now at twenty-four describes herself as something of a parent to her parents, who rely on her to help navigate technologies as well as bureaucracies. “Something that is sometimes frustrating is that they think we know how to do everything.” It’s a common generational issue for immigrant families.

Vanessa, like many others, feels the impact of gentrification in Oakland. In 2019, the mid-point for monthly rent for a one-bedroom apartment in the Deep East was $2,300. 34I hear the stress in Vanessa’s voice as she leans forward: “This is the ‘ hood .’ If Latino, low-income communities can’t afford it anymore, well, shit, where do we go? We obviously can’t afford to live in nicer, affluent communities. If we can no longer afford to live in low-income communities that are considered dangerous, that are considered poor, then where do we see ourselves?” Vanessa answers her own question. She’s been watching Black and Brown families move from the Deep East to Tracy and Stockton, “cities where there’s essentially nothing,” sighs Vanessa.

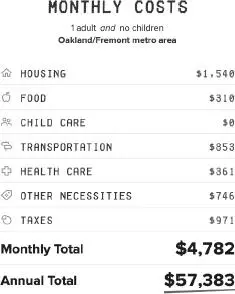

“My mom sells tamales once a week, and my dad’s a laborer. I’m the one who has the job, a good social. 35So I think that’s kind of pressure on me too to make sure that I stay well off so I can support myself and support my family. I am already at a big advantage: I speak English, I was raised in this country, and I have a four-year degree.” Vanessa works for an educational nonprofit that serves Latinx high school students. It’s a professional position that comes with health insurance and a salary that she ballparks between $45,000 and $59,999 a year. This puts Vanessa in the ballpark for the Economic Policy Institute calculations for self-sufficiency for a single person. By these numbers alone, she seems solidly middle class. But life is always more complicated than numbers. On paper, Vanessa is single. In reality she is responsible for her parents and younger siblings. Vanessa tells me: “If I wasn’t supporting my family, then I wouldn’t be considered low income, but a chunk of money and resources goes toward my family and it’s definitely more challenging.” There’s more to be said about this later. For now, it’s also worth noting that she remains tethered to the struggling class in other ways. For example, although she has health insurance, the Deep East is isolated from health-care providers. To get health care, she needs to take public transit, which can mean taking multiple buses to a different part of Oakland. For Vanessa and her family, there is no such thing as an easy, or a short, trip to the doctor.

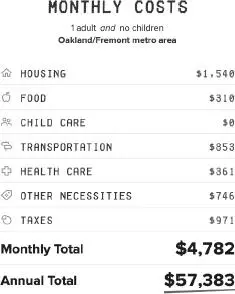

Again, keep in mind that Fair Market Rent (FMR) – the standard calculation used here – is quite different from actual housing prices. Sixty percent of local housing is more expensive than this. The reality of the rental market in 2019 meant that studios in Oakland went for $1,761 a month ($21,132 per year). We saw in Chapter 1that HUD’s definition of affordable housing, includes utilities and costs no more than one-third of your pre-tax income. While most rentals do not include utilities, let’s bracket that issue and look just at the monthly rent. Using HUD’s parameters for assessing affordable housing, a renter would need to earn at least $5,283 a month or $63,396 a year to be able to consider a studio in Oakland affordable. Vanessa’s salary is not enough to enable her to afford this studio without becoming what HUD calls “cost burdened.” That is to say, she would have to pay more than 30% of her income for housing. The lack of affordable housing is the source of a lot of misery. A person living at the federal poverty line ($12,140 per year for a single person) could put 100% of their income toward rent and still not cover the cost of an average studio apartment. The federal recognition of poverty comes long after the point when housing in Oakland becomes unaffordable.

The self-sufficiency budget of $57,383 for a single person is in the neighborhood of what Vanessa earns – but it’s hard to say precisely, since we only have a ballpark figure for her income. To fully support herself and four others (two parents and her two youngest siblings), Vanessa would need to earn $156,717 a year. It isn’t clear to me just how fully she supports her family, but it becomes easy to see how quickly circumstances move Vanessa from middle class to low-income. This is exactly why income alone never tells the full story.

Even so, when I notice that Vanessa has $20,000 in savings, I am ready to cancel the rest of the interview. And then she explains that she and her family cut corners to save money as if their lives depend upon it – because they do. “I feel like me and my family have tried really hard to save money,” explains Vanessa, “because I’m undocumented. My parents are undocumented. My brother’s undocumented, so I know that there’s no safety net for us. For example, my parents are not working right now [because of the pandemic], and they can’t get unemployment. I want to make sure that I try to save up every penny as possible, because we don’t know if there’s going to be a situation within our family.” Vanessa’s income is critical to her family, which includes a younger American-born sibling who would be left alone if the family was deported. According to the Marshall Project, there are about 10.7 million undocumented immigrants in the United States, and, nationwide, “about 908,891 households with at least one American child would fall below federal poverty levels if their undocumented breadwinners were removed.” 36

Читать дальше