The hairdresser must first know the most varied materials and procedures for colour changes; she must show the customer the possibilities and limits and choose the right material based on their wishes (knowledge).

In order to be able to correctly use the product, the hairdresser must understand the application procedure. She must know the consequences of not adhering to the recommended exposure time but must likewise understand that there are different application techniques for different situations. Therefore, she must consider the actual situation.

Once the hairdresser has decided on an application technique and a product, her skills come into play. When mixing the colour, she considers the exact instructions for use and follows them carefully and correctly. In the end, again, attitudes play a core role when she assumes responsibility for careful execution and adheres to the application time.

1.1.1 Our understanding of competency

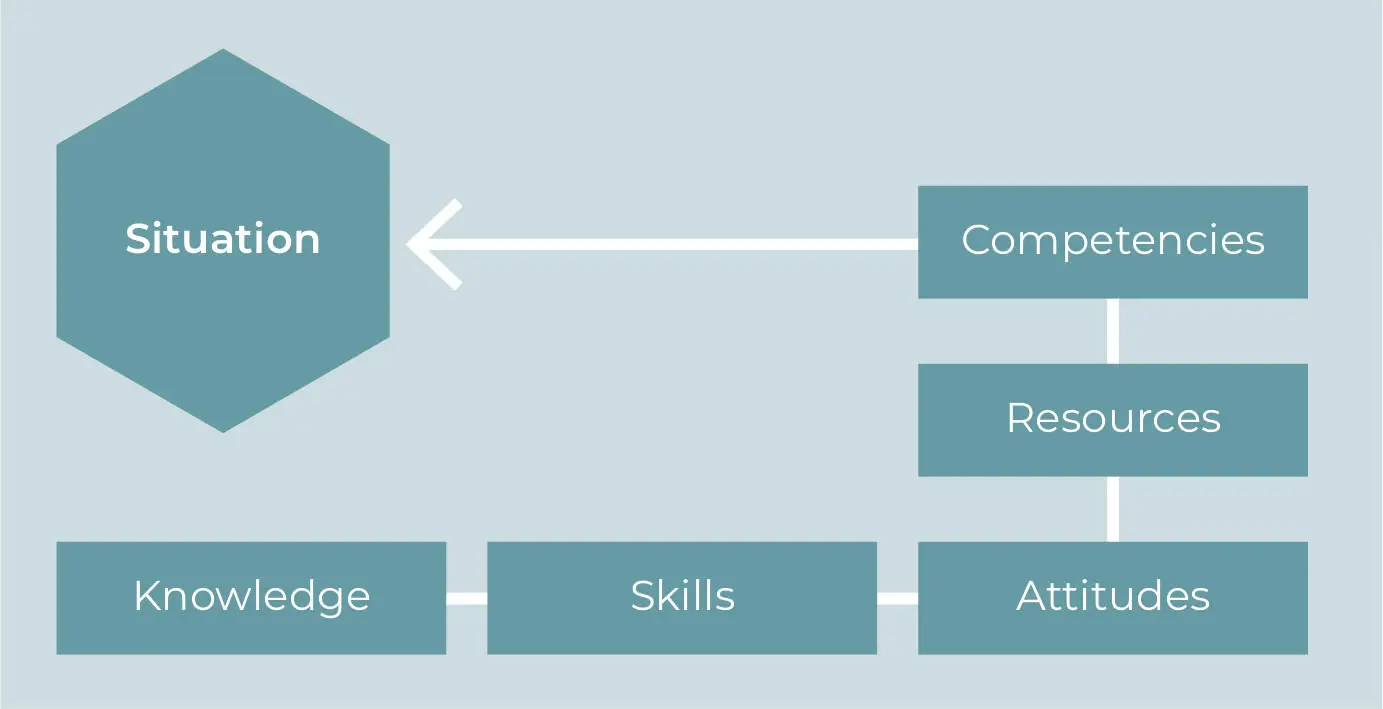

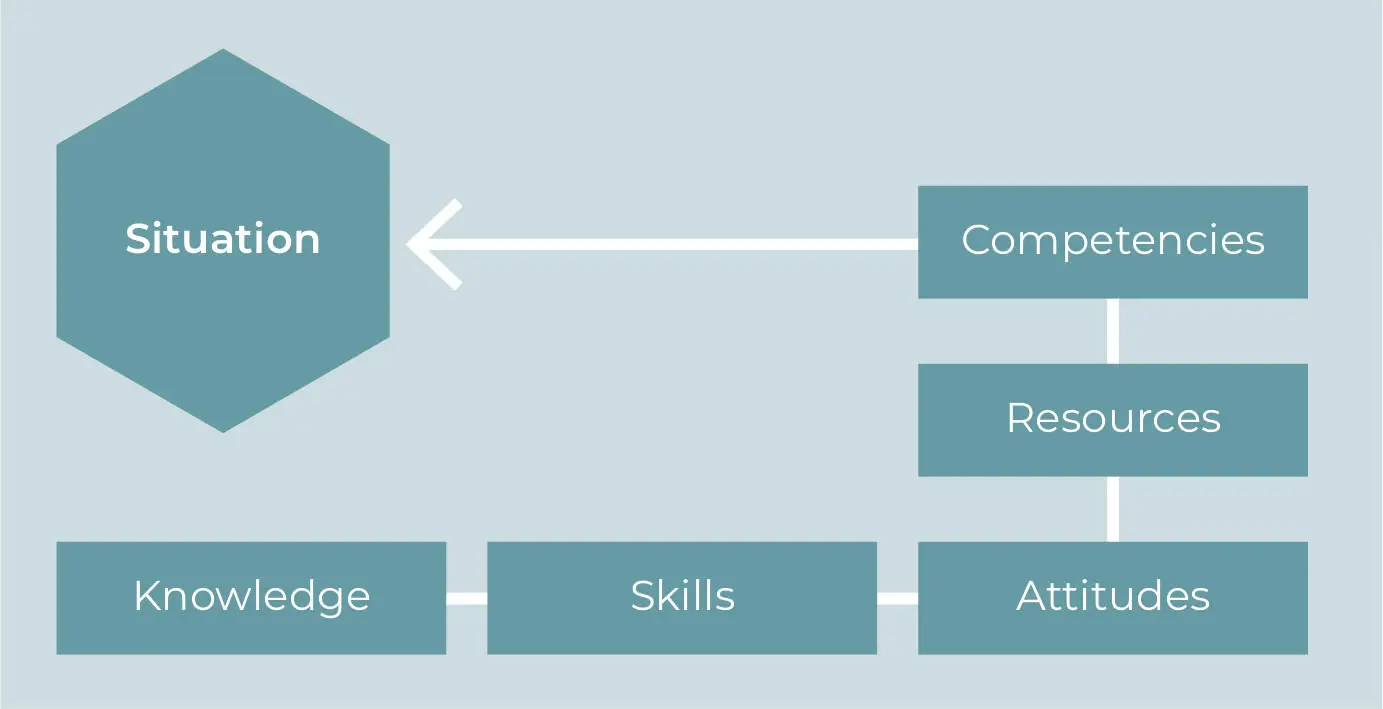

Just as in the example above, in this book we use the term competency to refer to a given capacity to activate certain resources – that is, knowledge, skills and attitudes – with respect to a particular practice and to combine these resources with one another in a creative and functional way in order to master concrete situations (cf. Figure 1and Ghisla, Bausch, & Boldrini, 2008, p. 441). We concentrate in particular here on the domain of schools, but note that what is transmitted and learned in school is just one part of the broader process of developing competencies. Conversely, it is very important that the knowledge, skills and attitudes that learners acquire outside school are embedded, used and reflected upon in the classroom. Teaching should always be linked to the experiences of the learners in the best, most productive sense.

Figure 1 The competencies-resources model

1.1.2 Knowledge, skills, attitudes

A few general notes on the three types of resources

Knowledge: Knowledge can take different forms (cf. e.g. Brühwiler, Hollenstein, Affolter, Biedermann, & Oser, 2017, p. 211). One form can usually be conveyed in statements and is therefore referred to as declarative knowledge. Learners must, for example, know technical terms, understand their meaning and be able to comprehend and name relationships between them. This type of knowledge, however, is not limited to factual contents. Declarative knowledge is also important in techniques for working and learning: learners gain knowledge about possible procedures and workflows. But even that, of course, is not enough. They also need the “know-how” to carry out that action using specific techniques, which we call procedural knowledge (cf. Euler & Hahn, 2007, p. 109). And furthermore, they need to know when and under what conditions they can use certain working and learning techniques to gain an advantage. Such expert knowledge, adapted to a concrete situation, is referred to as conditional knowledge. Finally, there is also what we call meta-knowledge: this includes the knowledge that a learner has about themselves (e.g. learning habits, personal repertoire of learning strategies), about the learning situation (Metzger, 2001, p. 43) and about specific tasks and various types of tasks (Büchel & Büchel, 2010, pp. 33–38).

Skills: Secondly, learners need to be able to apply their knowledge in certain situations. For this they need specific skills, i.e. an observable ability to perform a learned psychomotor action, which, in many cases, is specifically developed through repetitive training (in the form of learning and working techniques), such that over time it becomes second nature.

Attitudes: Thirdly, the values and norms a person holds are important, as they substantially influence behaviours. Responsibility, empathy, tolerance and interest in the environment are important attitudes of a competent practitioner.

Based on these definitions of “resources”, we propose the following principles for our book:

1.If a competent practitioner requires the ability to mobilise resources, then these resources must already be to hand, and the function of the school is to develop and systematise them.

2.Competence is always situational – and every situation is different. However, situations can also be typified and simulated, which is a central assumption of school education.

1.2 Core elements of the AVIVA model

The design of the lesson has a substantial influence on the way in which learning goes on in schools. If the teacher always controls every single activity in the classroom, learners will never be allowed to manage their own learning. Equally, if the teacher entrusts learners with the responsibility of defining the contents and methods of their own learning process, it is unlikely that the learners will acquire the requisite knowledge and skills, as they will not know how they should proceed in certain situations. Therefore, it is essential to strike a good balance between control and instruction by the teacher, on the one hand, and elements of self-regulated learning by the learners, on the other, according to a clear roadmap of the phases the lesson has to go through. It is this phase model that has given AVIVA its name. To better understand this model, we must consider some further essential elements:

1.2.1 Three-layer model of learning

Learning – be it in school or elsewhere – is a complex process, the important aspects of which (cf. Reinmann-Rothmeier & Mandl, 2006; Reusser & Reusser-Weyeneth, 1994) must always be taken into consideration in the lesson:

1.Learning is an active process. Learners must develop the motivation to learn, with regard to both the specific subject matter they are dealing with and to the general activity of learning.

2.Learning is a self-directed process. Learners use their initiative to control and monitor the process of learning (to varying degrees according to the type of lesson). Learning without some degree of self-direction is inconceivable.

3.Learning is a constructive process and always builds on existing resources. Without a corresponding background of experience and knowledge, and without the learners’ own strong contribution to this process of construction, there will not be sustained cognitive engagement.

4.Learning is a situational process that always takes place in specific contexts. Situations provide concrete learning experiences and deliver an interpretative basis for the evaluation of resources.

5.In learning, emotional processes are of great importance. Performance-related and social emotions have a great impact on motivation and competence.

6.Last but not least, learning is also a social process. Learning frequently takes place in a context of social interaction – peers, contemporaries and fellow learners play a role alongside teachers and trainers.

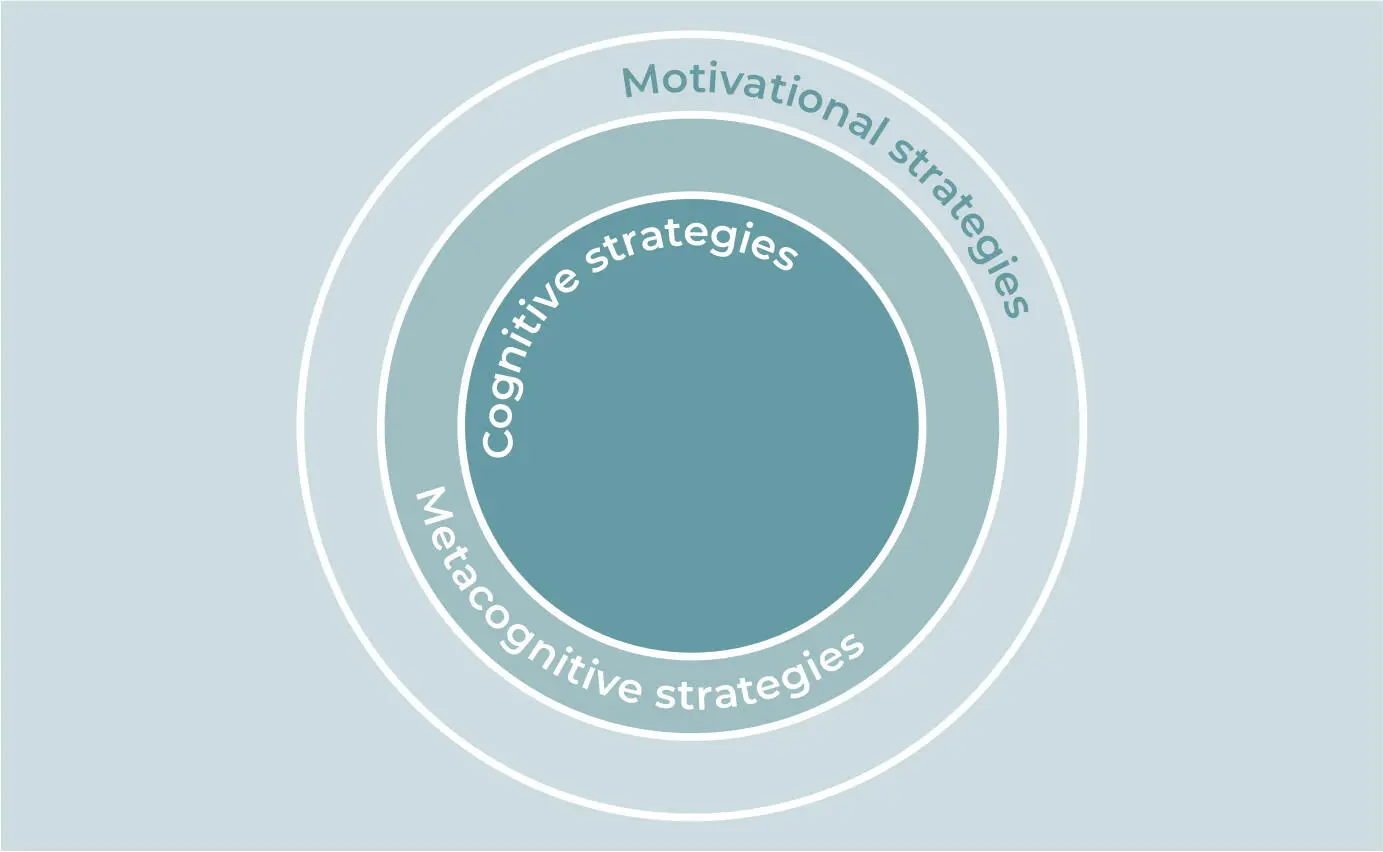

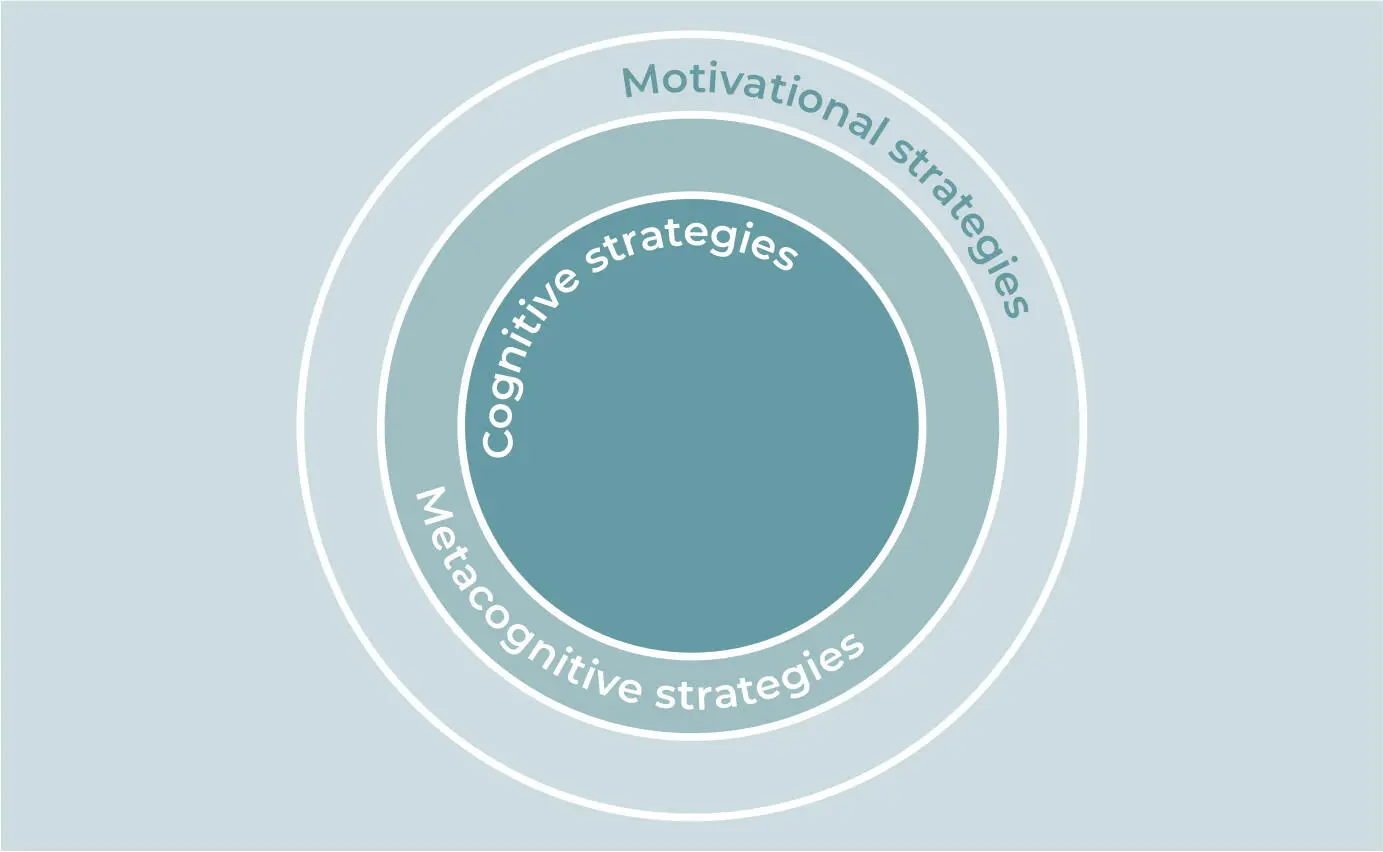

In addition, learning requires the deployment of various strategies: not just cognitive and meta cognitive strategies but of course also motivational strategies. We use the term strategies very deliberately; strategies have to do with complex ways of thinking and working and are therefore more than mere “techniques”. Strategies are employed with intention and clear aims; they are monitored as to their effectiveness and are adjusted as necessary. The three strategy components are positioned in layers (cf. Figure 2).

Figure 2 The three-layer model of learning

Cognitive strategies form the core: by cognitive strategies we mean all those processes that are directly related to the acquisition, processing and storage of information. We differentiate between surface strategies – oriented mainly towards the reproduction of knowledge (a more cumbersome learning process, involving reading a text several times and memorising the content, etc.) – and deep strategies, which are used to really understand the content, separate the important from the unimportant and discover connections.

Читать дальше