Next I introduce the First Path, the self. The first path of the journey is a deeply personal one. The path is inward, where we learn to love ourself and recognize our own fundamental human worth. It is important for two reasons: First of all, learning to love ourselves and recognize our worth is fundamental to our being. Full Stop. Secondly, at work, we may encounter obstacles that will regularly challenge our intrinsic worthiness. And if we show up feeling unworthy at work, we act out of it to the detriment of ourselves and others. In Chapter 5,I define self-love and self-worth and share some of the history of self-love, as well as how I discovered to love myself. I then investigate some of the surprising things we learned in our research about how different people of different backgrounds and identities learn to experience self-love in the face of an inhospitable society. In Chapter 6,I explore the ways in which we can cultivate self-love and self-worth by accepting ourselves “in our being,” with our words and with our actions. Chapter 7acknowledges all of the obstacles we will face on the path, including the obstacles from ourselves, from another in our lives, and from the communities of which we are a part.

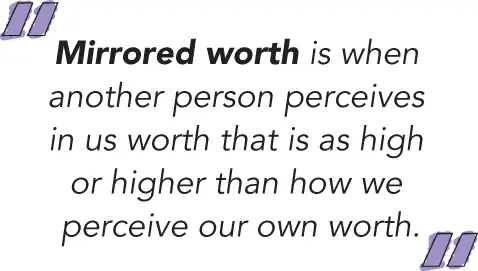

The Second Pathis about the journey to loving and recognizing the worthiness of “Another” in our lives. We shift the lens from cultivating love and worth for ourselves to focusing on how we can cultivate love and worth for another person in our lives. Chapter 8begins by exploring the connections we seek to other individuals, and how these connections bring us meaning. I then introduce the idea of “mirrored worth,” which is when another person perceives in us worth that is as high or higher than how we perceive our own worth.

Chapter 8ends with a discussion of the four types of allies we can be for each other in our journey to growing in love and worth: a friend, a mentor, a sponsor, and a benefactor. We become a better ally when we consciously and intentionally give our support, our voice, our power, or all three to another. We reach out. We speak up. We show up. Chapter 9introduces the ways we can cultivate love and worth for another by accepting them “in their being,” with our words and in our actions. Chapter 10concludes the second path with a discussion of the obstacles we may face on the journey.

The Third Pathis the path of learning to love and recognize the worth of others whom we meet at work every day. It is about challenging and changing the systems that would tell us—and have told us for a very long time—that there are those who are not worthy or loveable. It is the path of becoming better at loving those in our communities of work who find themselves systematically marginalized, unseen, and unrepresented just for being. For being female. For being Black, Brown, or Asian. For being gay or transgender. For being too old or too young. For being a person with a disability. For being any of these intersections. For those of us wrestling with what it means to be privileged White, privileged male, or both, at a time when the systems that were designed to serve Whiteness and maleness are badly in need of redesigning to recognize love and worth. This third path is of critical importance if we are going to create places of work where we can all show up as our whole worthy selves, recognizing what we value as humans, acknowledging the need for emotional connection, and building trust. On this path, I draw on my specific lived experiences as a management consultant first at the Monitor Group and then as a partner in Deloitte. In Chapter 11I explain how we do the work collectively of elevating the human experience for each other at work. Chapter 12is about cultivating love and worth at work. I introduce the research and work we did to learn to see and acknowledge our colleagues' worth at work. Chapter 13, similar to the earlier paths, ends with a discussion of the obstacles we may face on the journey.

I then end with Resources,which you can find in Chapters 14 and 15, where I introduce the tools and the capabilities we may need on the journey of each of these three paths. The tools include ways of better understanding the role of values, emotions, and trust, all central to elevating the human experience. The capabilities include empathy, courage, integrity, and grace.

I offer this book as an inspiration and as a guide on the path of your journey to making your experience of being human just a little bit better, to feel more loved and more worthy at work. The three paths are very much a personal journey. Please use this book as a guide to refer to the foundations, the paths, and the resources that might help you along the way. My own journey is far from done. But like a guide who has been up and down a mountain before, I hope to point out an easier path for you to get to the summit faster and with greater ease than I ever did. And then to do it again.

Foundations

Your work is to discover your work and then with all your heart to give yourself to it .

—Buddha

A Personal History of Work

As a single parent, my mother worked as a teacher at the Catholic school my brother and I attended so that she could keep the same schedule as we did. She taught me sixth-grade science and math. I remember thinking how ironic it was that she would help me with my science terrarium at night and have to grade it at school the next day. On weekends I got extra practice on decimals, percentages, and fractions as she had me calculate coupons and sale items when we went grocery shopping at the local Publix. It blew my fuses to learn that you could take 70% off of an item that was already 50% off. We rarely bought anything “full price.”

At 17 years old, I went to Harvard, where I studied sociology and worked as everything from an aerobics instructor to a librarian shelving books. Later, my mother and I would laugh about the fact that I was the girl from Fort Lauderdale who showed up freshman year prepared for Boston's subzero winters with three cotton sweaters, a fashionable fedora-style hat, and cotton socks. I didn't understand that I had just entered a world where I would be surrounded by an easy privilege that I lacked, as obviously as I lacked wool, cashmere, and fleece. I was almost daily reminded that I did not quite fit in, and I clung to my unworthiness like a familiar well-worn blanket that reminded me of home.

Upon graduation, I enrolled in a master's of theology program at Weston Jesuit School of Theology, across the common from Harvard in Cambridge. While my friends got “real jobs” in management consulting and investment banking, I had the idea that I might somehow bring sociology and theology together towards a PhD in social theory and theology. I was searching but didn't know yet what it was I was searching for.

One year into graduate school, I found that I needed to earn more to support myself than what I could earn working part time in Widener Library on campus. I put my resume together and landed a well-paid summer internship at the Monitor Group, a management consulting firm in Cambridge. The firm caught my eye because it was the only one that used the words “moral purpose” in its brochure to describe its work. As a theology student I was intrigued about what moral purpose could possibly mean in the world of business. And so I became a management consultant in the summer of 1998, a job that is a mystery to most people. I often describe the work of management consulting as the work of problem solving. If there were no hard problems, there would be no need for consultation. There I learned what it meant to have my first mentor, Enshalla Anderson, a Black woman with degrees from the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard Business School, sit me down late at night and patiently teach this theology student how to calculate the net present value of a potential investment. I made dear lifelong friends. And I learned what it felt like to have bosses who were both allies and benefactors, able to see in me a worth that I could not yet see in myself. At 23, I graduated with a master's degree in theology and accepted the full-time offer from Monitor. I don't remember exactly how much I earned in my first year of employment as a theologian-turned-management-consultant. I do remember, however, that it was more than my mother had made in her last year of teaching in an almost 20-year career.

Читать дальше