No doubt my mother and father would have explained to me in whatever words they could summon, words that left no memory, that they were getting a divorce. It wasn't unusual, or traumatic to anybody else except my brother and me. We felt, both he and I, marked as different. We noticed that in our new life that we were the only kids on the block living with their grandmother and not with two parents. I felt that I was not worthy of the perfect mother plus father, plus two kids love square, which we saw on every American television channel and heard in every story book in the early '80s .

The rest of my early childhood looked normal. I started taking dance classes on Saturday mornings. I made my first friend and First Holy Communion in second grade. We rode our bicycles to Dairy Queen to get soft serve ice cream. The Domino's pizza delivery man came to the door some Friday nights. We jumped waves at the beach. But still I knew something was not quite right. I was a bowl-headed, British-accented girl who burned easily in the sun. I wore a neon green nose plug so that I didn't get water up my nose, infecting the scar tissue in my ears. I still burn with shame at my ridiculous-looking, near-blind, near-deaf unworthy little girl self .

My brother reminded me that we each tried to run away more than once, to run away from that uncomfortable, unworthy feeling. I remember the need-to-get-away feeling when there seemed to me no cure for the way I felt. I can still see my mother calling for me to come into dinner while I hid high up in the tree in the front garden of my grandmother's house where she would not see me in the growing dusk. I remember her voice changing to higher pitches of urgency as she called and called and called my name. The urgency in her tone shifted to anger. I let her feel fear and anger. I felt fear and anger too. Like my mother, I didn't have words to express my complicated feelings, so I hid instead .

From my early childhood experiences, I learned at a deep subconscious level that I was not worthy. My feelings of unworthiness needed to be hidden at all costs. Nobody asked that little girl how she felt about leaving her country, her father, her school, her neighborhood, her house, her bedroom, and her hair behind. With my crooked finger, near-sighted eyes, and near-deaf ears, physically I was certainly less than whole. My memories came with near endless tears. I told myself that I had the “gift of tears” because I cried most days of most weeks of most years. I just thought that was what you did—that was the experience of being human .

I wondered and hoped that maybe I would someday feel worthy of love, if I just worked hard enough or fell in love like they did in storybooks. I wondered if there was a different, better experience of what it meant to be human beyond my reach, but that other people around me seemed to experience. I realize now I suffered as a child. I say that not in any way to blame my mother and father, who raised me as best they could, and equally not to say that my suffering was any flavor of special. While my experiences may have been unique, my suffering was the incredibly ordinary universal kind. But to little-girl me, the feeling of suffering filled my universe. It was my struggle. What I didn't realize then is that it was my suffering that made me most normal, most human. Suffering did not make me unworthy of love. It made my story the same as the story of everyone else who struggles at times to feel worthy of love, which I could never possibly know .

This book is for people who know what it is like to struggle to feel loved and worthy, when they show up at work. You may struggle to bring your femaleness or maleness, your motherness or fatherness, your Blackness or Brownness, your gayness or Lesbian-ness, your real identity authentically to work. It is also for the people who have no idea what it may feel like to struggle every day to feel loved and worthy, but love people and lead people who do .

For me, the journey to find the love and worth that makes the experience of being human somehow better, somehow elevated, is a personal one. Although there are times I still very much want to hide my real self up in that tree in my grandmother's garden again, I am learning to come down out of the tree, to show up as my real, vulnerable, authentic self, even at work. Especially at work .

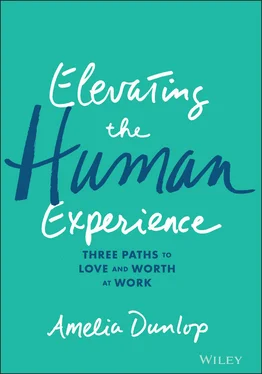

The first time I heard the phrase elevating the human experience was at work. It was the spring of 2018 in a meeting with my new boss and his newly formed leadership team. I thought, “He is crazy if he thinks we will ever say those words out loud to each other, much less to a potential client.” They sounded like an aspiration, worthy of striving towards but just out of reach. I wondered what they could possibly mean for me, for my colleagues in the world's largest professional services firm, for our clients and the people they served. For some of my peers, who had been laboring and loving quietly for years, the words were affirming and inspiring like a Zen koan: You know you have elevated the human experience because your heart feels full when you are done . For others, the words “elevating the human experience” were easy to mock, for all of the ways we daily fall short of living up to them in the workplace, for all the ways we feel anything but worthy of love when we show up at work.

I can hear the objections now. “Love is best left squarely in the domain of one's personal life,” so let's define love. Love is not a warm feeling or attachment. It is not only about the romantic or erotic. There is a lesser-known version of love the Greeks called eudaimonia , often translated as “human flourishing.” Building on the Greeks, and adapting from Eric Fromm's The Art of Loving , let's define love as the choice to extend yourself for the purpose of your own or another's growth.We grow people and we grow things that we care about. The outcome of this love is flourishing.

Equally, my philosophy of leadership is a philosophy of love. People become, people grow, and people are capable of remarkable things when you believe in and love them . These people are our family members and friends. And these people are our co-workers, because our co-worker is child to some parent, friend to some friend, all worthy of love.

“Worth” is often used to mean something or someone's extrinsic value that can be externally verified. It is the sort of worth derived from something else. But it can also mean something or someone's intrinsic value, just for being, before they say or do anything. This book is about love that leads to growth and worth that is intrinsic to each of us. Putting them together, Elevating the human experience is about acknowledging intrinsic worth as a human, and nurturing growth through love.Sometimes the person we need to see as most worthy of love is ourselves. Sometimes it is another person. Sometimes it is a group of people who have been unseen.

There is an overabundance of books about the possibility of transformative growth for individuals or transformative growth for organizations. Digital transformations. Customer transformations. Employee transformations. But how do you transform an organization, which is a community of living and breathing humans, if you don't grow and transform the humans? How do you build a movement to inspire and motivate people to think, believe, and act in new ways? Where is the new source of untapped potential energy if not inside the human heart and the transformative capacity to love? There are compelling visionary leaders who know intuitively how to tap into the heart as well as the mind, but what about the rest of us who show up to work every day? How do we tap into the transformative power of love and intrinsic worth that helps us flourish in our lives and in our work?

Читать дальше