Pathology of Genetically Engineered and Other Mutant Mice

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Pathology of Genetically Engineered and Other Mutant Mice» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Pathology of Genetically Engineered and Other Mutant Mice

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Pathology of Genetically Engineered and Other Mutant Mice: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Pathology of Genetically Engineered and Other Mutant Mice»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

An updated and comprehensive reference to pathology in every organ system in genetically modified mice Pathology of Genetically Engineered and Other Mutant Mice

Pathology of Genetically Engineered and Other Mutant Mice

Pathology of Genetically Engineered and Other Mutant Mice — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Pathology of Genetically Engineered and Other Mutant Mice», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Sources: Diagram (by Tim Vojt, The Ohio State University) and photograph (by Dr. Elizabeth R. Magden, Colorado State University) both from Newbigging et al. [70] with permission of CRC Press.

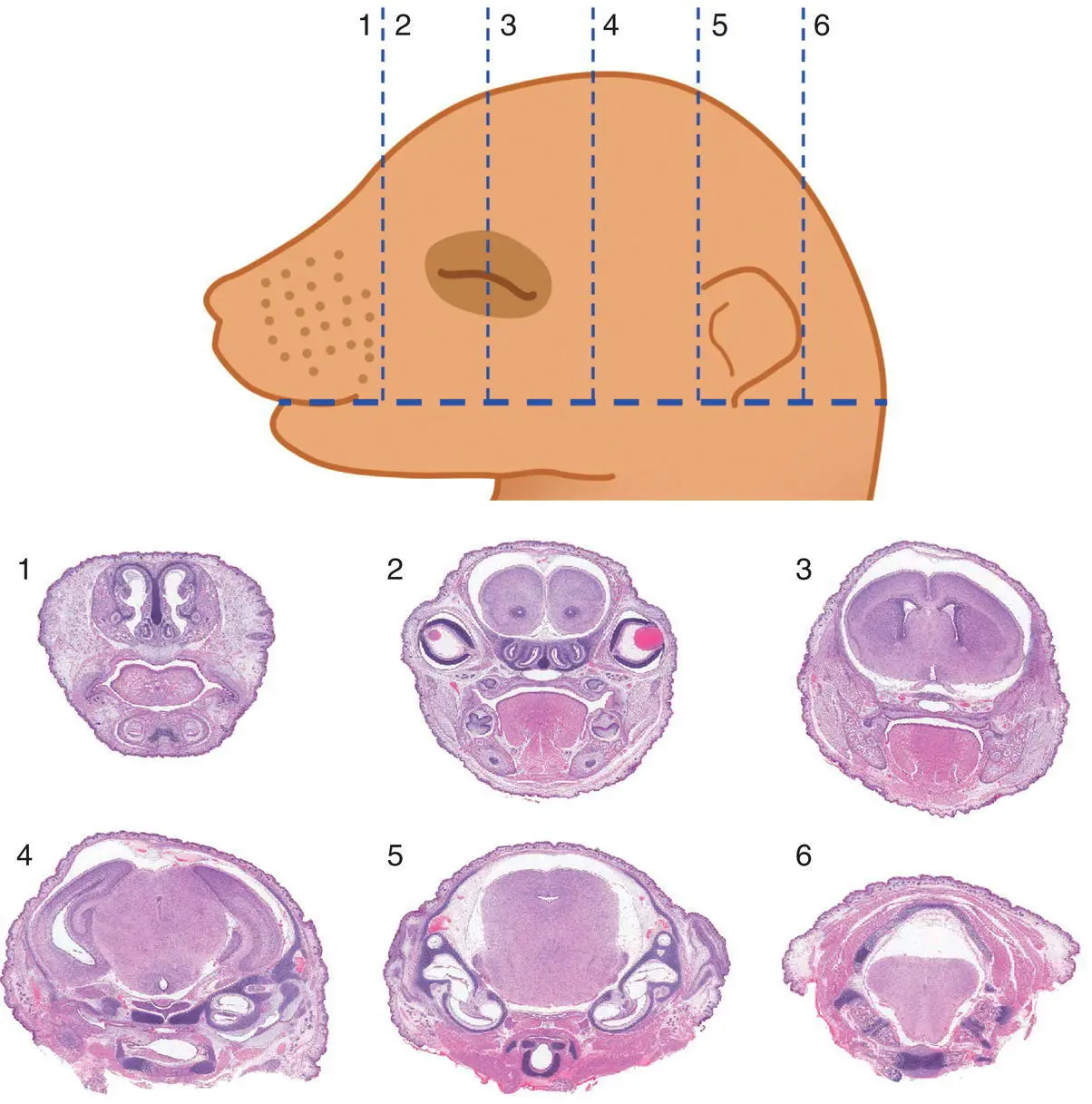

Figure 5.11 Sectioning (Wilson's) technique to allow macroscopic evaluation of brain defects in near‐term (GD17 and older) mouse embryos and neonates. The numbers identify the position of the tissue block located between two adjacent incisions (dashed lines). Should a microscopic examination of the blocks be desired, the cut surface closest to the number identifying the block should be placed “down” in the cassette. Tissue processing: Bouin's fixation, paraffin embedding, H&E staining. Stain: H&E.

Source: Diagram by Tim Vojt, The Ohio State University; all images from Newbigging et al. [70] with permission of CRC Press.

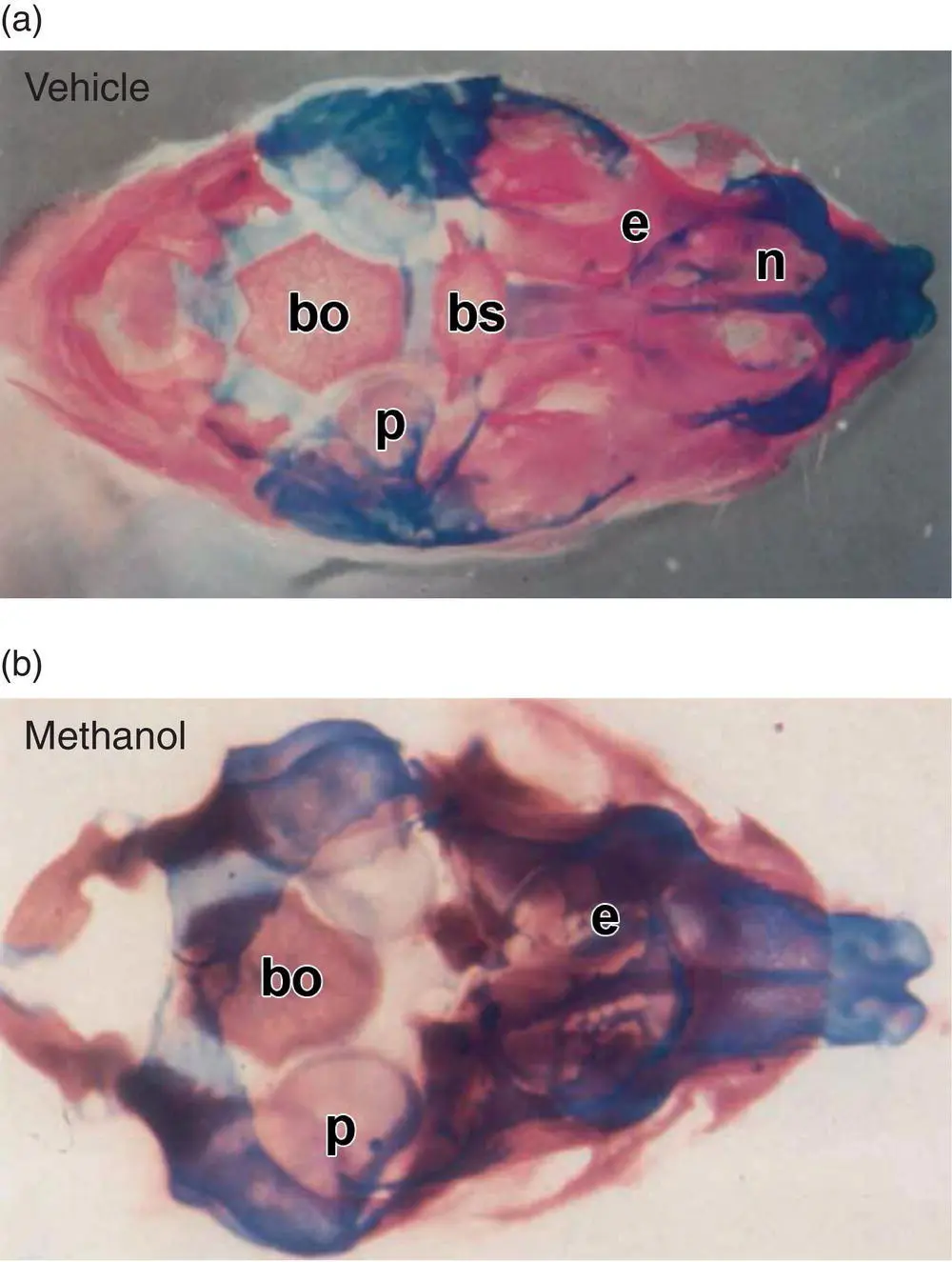

Figure 5.12 Skeletal double staining may be used to characterize axial patterning defects in near‐term mouse embryos (here GD17) and neonates, with Alcian blue utilized to highlight cartilage while Alizarin red is used to show bone. Panel (a): Vehicle‐treated embryo with normal basal cranial structures. Panel (b): Methanol‐exposed exencephalic embryo (following maternal inhalation throughout neurulation [GD7–9]) showing malformed basal cranium bones exhibiting less cartilage to bone conversion. Abbreviations: bs = basisphenoid, bo = basioccipital, e = ethmoid, n = nasal, p = petrous temporal bone.

Source: Bolon et al. [97] with permission of John Wiley & Sons.

Figure 5.13 Developmental anatomy of a wild‐type GD16.0 mouse embryo demonstrating the anatomic relationship of key structures when viewed in mid‐axial section. Major organs are specified during organogenesis (the period from approximately GD8.0 to GD15.0), and near‐term are fairly easy to recognize with the aid of well‐annotated developmental anatomy atlases and their similarity to adult positions and contours. Major exceptions to this rule are the cerebellum (arrow) and lymph nodes, for which anlagen (organ primordia) form prenatally while the bulk of differentiation occurs after birth. Stain: H&E.

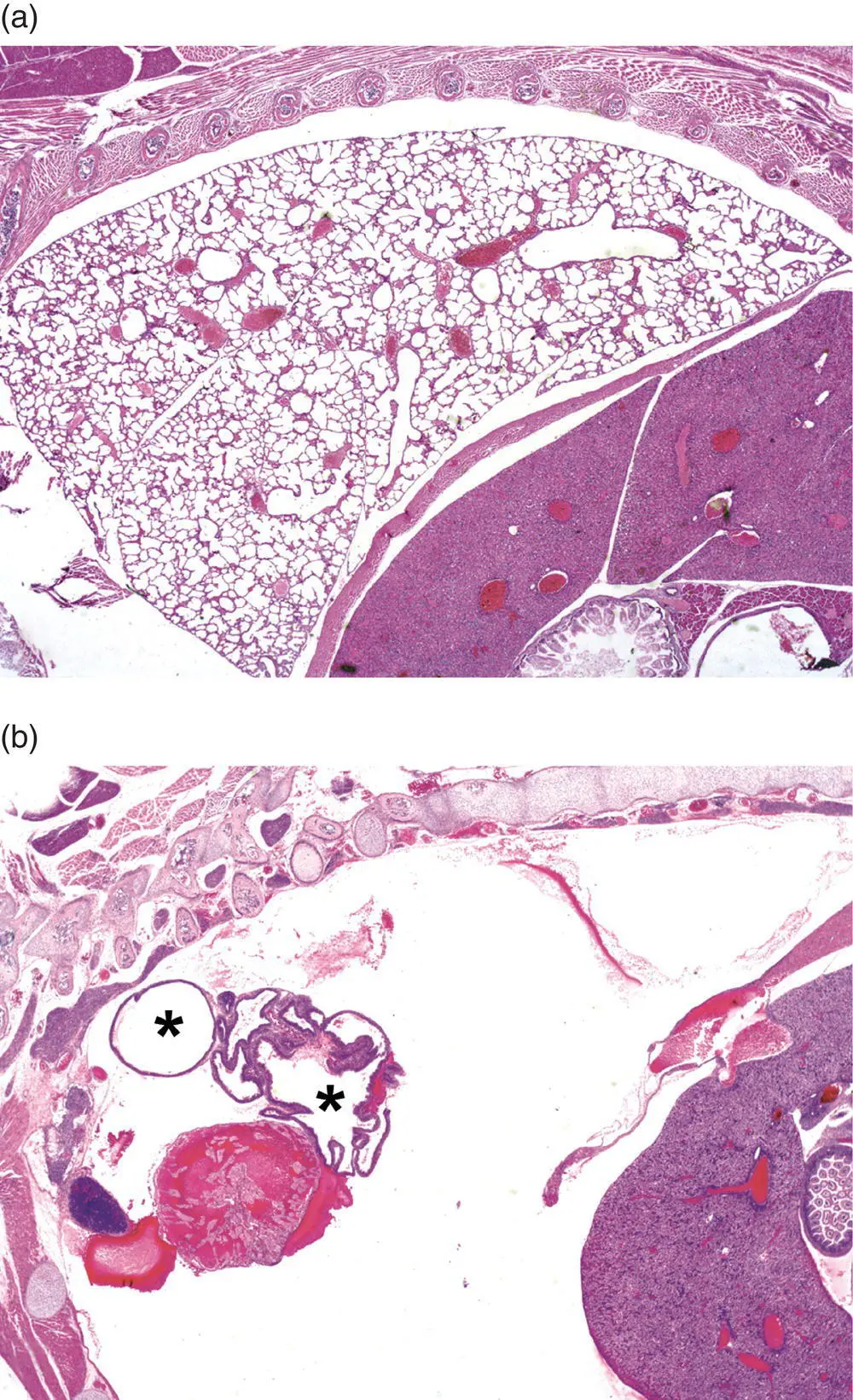

Figure 5.14 Missing structures represent a special situation in developmental pathology. In some cases, their absence is obvious – as is seen here by comparing the normal appearance of expanded air spaces in the lung parenchyma of a wild‐type (WT) mouse neonate (Panel (a)) to the thoracic cavity of an NK2 homeobox 1 ( Nkx2‐1 tm1Shk) null mutant (KO) mouse neonate, which lacks all lung tissue except some cystic remnants (asterisks) representing aborted lobar development (Panel (b)). The absence of smaller organs or individual cell populations may be more subtle, and the tendency of the mind to “fill in” missing features may lead to a missed phenotype if the phenotypic evaluation is undertaken in a cursory manner. Stain: H&E.

Readouts for mouse developmental pathology endpoints may be confined to qualitative scores (i.e. “normal” or “abnormal”) and detailed descriptions of lesion, but in many cases, potential developmental phenotypes are better judged by assigning semi‐quantitative lesion scores [76]. A common scoring scheme typically includes multiple tiers: within normal limits (score = 0), or minimal (1+), mild (2+), moderate (3+), or marked (4+) lesions. Each tier must be founded on well‐defined criteria, which generally should be stated explicitly in publications to ensure their reproducibility by investigators seeking to interpret or replicate the results.

Clinical Pathology Evaluation of Developing Mice

Many mouse developmental pathology assessments are limited to anatomic pathology evaluation of macroscopic and microscopic defects. Clinical pathology analysis for mouse developmental pathology experiments usually is confined to hematology (in whole blood), clinical chemistry (in serum), or organ cytology. These samples are collected due to the common role of cardiovascular dysfunction and hematopoietic defects in developmental lethal phenotypes [8, 77]. Common tests performed for mouse developmental pathology projects, since they need only a small blood sample, are an automated complete blood count (CBC) and a limited chemistry battery (albumin, blood urea nitrogen, calcium, glucose, phosphorus, total protein).

Blood collection for developing mice typically is undertaken as a terminal procedure since embryos and neonates have a very small blood volume. Common sampling options are decapitation and cardiac puncture [58, 77]. Blood is harvested into standard collection tubes (e.g. Microtainer ®). Greater blood volumes may be obtained from outbred mouse stocks relative to smaller inbred strains. In our experience, enough blood may be harvested from a single neonatal mouse (1.5 g or larger in weight) to permit either a CBC or a serum chemistry battery, but not both. Alternatively, collection of blood in a tube containing potassium or sodium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) as an anti‐coagulant may allow measurement of both a CBC (from whole blood) and a very few chemistry values (from plasma obtained by centrifugation of the sample). For small subjects (embryos from GD15 to term), sample volumes typically need to be extended either by mixing whole blood with an equal volume of physiologic saline (pH 7.4) or by pooling blood or plasma samples from mice that have an identical genotype and/or that received the same treatment. In our experience, pooling blood from two (at GD18.5) to four (at GD15.0) embryos will provide enough sample for either a CBC or a chemistry battery, but not both.

When investigating some lethal phenotypes, cytological assessment of isolated cells may be necessary to define the pathogenesis [58]. Cytological evaluations permit assessment of cellular and subcellular features at high resolution. Techniques such as smears for blood and bone marrow and either squash or touch preparations for organs with dense parenchyma like liver, spleen, and thymus are particularly useful in this regard. In general, results from cytological methods should be interpreted along with findings from conventional histopathological evaluation so that both tissue organization and individual cell characteristics can be assessed. For most embryo phenotyping projects, microscopic examination of tissue sections is used for the initial screen for both cell and tissue lesions, while cytological methods are employed as a secondary procedure when warranted to better understand the nature of the changes first identified by histopathologic analysis of cells within the context of their usual tissue organization.

Pathologic Patterns in Mouse Embryos and Neonates

Gene targeted (null mutant or “knockout” [KO]) mouse embryos, and less often transgenic mouse embryos, develop abnormal organ‐ or tissue‐specific lesions due to the functional abnormalities arising from altering the role of the genetically engineered gene at different stages of normal development. In large‐scale knockout mouse programs, about 30% of all inactivated genes lead to developmental embryonic defects at various stages of gestation [78, 79]. In one study of 242 developmental lethal knockout mouse lines, 44% of lethal events occurred before GD9.5, 17% from GD9.5–12.5, 4% from GD12.5–18.5, and 36% from GD15.5 to weaning [78]. The specific developmental defect(s) in the 242 lines were not determined.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Pathology of Genetically Engineered and Other Mutant Mice»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Pathology of Genetically Engineered and Other Mutant Mice» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Pathology of Genetically Engineered and Other Mutant Mice» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.