Pathology of Genetically Engineered and Other Mutant Mice

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Pathology of Genetically Engineered and Other Mutant Mice» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Pathology of Genetically Engineered and Other Mutant Mice

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Pathology of Genetically Engineered and Other Mutant Mice: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Pathology of Genetically Engineered and Other Mutant Mice»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

An updated and comprehensive reference to pathology in every organ system in genetically modified mice Pathology of Genetically Engineered and Other Mutant Mice

Pathology of Genetically Engineered and Other Mutant Mice

Pathology of Genetically Engineered and Other Mutant Mice — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Pathology of Genetically Engineered and Other Mutant Mice», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The stage at which injury (lack of normal development of the entire embryo, or specific tissues or organs) occurs will determine the outcome of developing mice ( Table 5.1). For harm prior to implantation (i.e. before GD4.5), significant interference to normal development usually will lead to death of the embryo, while modest effects may engender developmental delays but minor consequences or no overt abnormalities. Such delays may undergo complete or partial compensatory repair as the remaining pluripotent stem cells restore lost tissue. Gross abnormalities (“birth defects” seen during gestation) most commonly result from damage incurred after implantation (GD5.0) but before the end of organogenesis (GD15.0), with the character of the malformation determined by the timing of the insult relative to various organ‐specific “critical periods.” For injury after organogenesis is finished (i.e. GD15.0 through the neonatal period), the embryo may exhibit slow growth or develop cell type‐ or tissue‐specific histopathological changes and/or functional abnormalities rather than gross defects; the exceptions to this rule are structures like the cerebellum and hippocampus that undergo major peaks of cell proliferation after birth. Embryonic lethality may result from many different causes, but common aberrations that reliably lead to death are decreased circulation (e.g. heart and/or vascular defects any time during gestation) and reduced oxygen exchange (e.g. erythrocyte deficiencies or hemorrhagic diatheses or placental insufficiency, especially occurring late in gestation).

Gross developmental defects that occur as spontaneous background lesions vary in frequency and severity among wild‐type (WT) mouse strains and lines. Minor incidental anomalies like renal pelvic cavitation (physiological hydronephrosis) and extra or wavy ribs are common (from 5% to 35% of animals) since they do not impact embryonic viability [80]. Major malformations like cleft palate and neural tube defects have low background frequencies (typically 0.5% or less) since they are lethal. An individual may harbor one or several minor or major abnormalities.

Table 5.1 Common embryonic or neonatal defects leading to lethality.

| Developmental stage | Developmental days when damage occurs | Target site for mutation or toxicant | Developmental outcome | Developmental timing of lethality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preimplantation | GD0–3.5 | Any cells (totipotent or pluripotent) | Embryonic death (no visible implantation sites) | GD1.0–4.0 |

| Postimplantation | GD4.5–5.0 | Any cells (pluripotent) | Embryonic death (no visible implantation sites) | GD5.0–5.5 |

| Gastrulation | GD6.5–9.0 | Altered germ layers or body plan | Embryonic death (empty implantation sites) | GD6.0–7.5 |

| Early organogenesis | GD8.0–10.5 | Cardiovascular or central nervous system defects, abnormal erythropoiesis | Mid‐gestational death due to cardiovascular or hematopoietic insufficiency | GD10.0–13.0 |

| Late organogenesis | GD11.0–15.0 | Defects in many organs, abnormal erythropoiesis, delayed growth | Mid‐ to late‐gestational death due to cardiovascular or hematopoietic insufficiency | GD13.0–16.0 |

| Near‐term growth spurt | GD15.5–18.5 | Altered cardiovascular function, abnormal erythropoiesis, delayed growth | Late‐gestational or perinatal death due to cardiovascular or hematopoietic insufficiency (or edema or hemorrhage) | GD16.0 to PND0.5 |

| Early neonatal | PND0 | Abnormal cardiovascular, central nervous system, cutaneous, musculoskeletal, or pulmonary function | Insufficiencies in circulation or respiration (inability to breath) | PND0–0.5 |

| Late neonatal | PND0.5–2.0 | Abnormal cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, metabolic, or neural functions | Insufficiencies in digestion or suckling (inability to feed) | PND1.0–2.5 |

| Juvenile | PND2.5–28 | Abnormal hematopoietic, immune, metabolic, or renal functions | Sustained anemia, abnormal immune function, metabolic or renal insufficiencies | PND3.0–28 |

GD = gestational day (where GD0 is the vaginal plug‐positive day), PND = postnatal day.

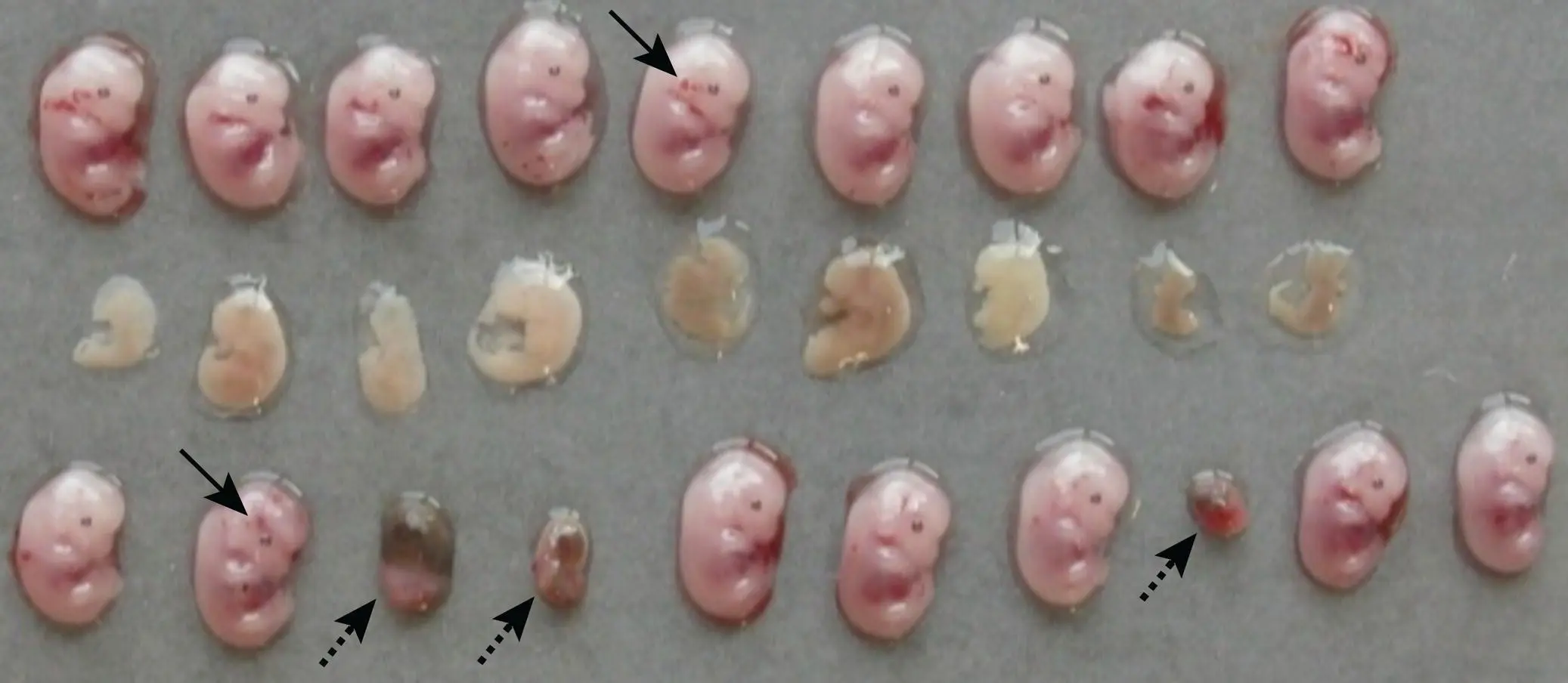

Frequencies of both minor and major defects may be increased by genetic manipulation, infections, or exposure to teratogens. Nearly 5000 abnormal phenotypes have been identified in mutant mouse embryos [79, 81], most of which are associated with monogenic null mutations (“knockouts”). Induced developmental defects have been reported in approximately 30% of genetically engineered knockout mice [78]. Bacterial and viral infections that can cross the placenta may lead to substantial tissue destruction of the embryo, placenta, or both. Numerous toxicants are capable of producing developmental phenotypes in rodents including agricultural and industrial chemicals, drugs, metals, and physical agents (heat and radiation) [82]. The kind of phenotype elicited by a genetic mutation or toxicant exposure will depend on where and when during development the gene normally performs its function. For example, in the brain anomalies in the cerebral cortex tend to arise from genetic defects that arise during mid‐gestation while abnormalities in the cerebellum – which develops late in gestation and after birth in rodents [42] – typically involve genetic dysfunction late in gestation or after birth. Knowledge of normal spatial and temporal patterns of gene expression during development is instrumental in allowing developmental pathologists to define potential target organs and more efficiently characterize developmental phenotypes. In general, the frequency and severity of developmental phenotypes will vary among litters, and among individuals of comparably treated litters. The variation in stages of embryo degeneration, necrosis and death, no matter the etiology, may be seen grossly [83] ( Figure 5.15).

Microscopic lesions of many cell types, and tissues and organs may be identified when phenotyping the tissues from developing mice. Identification of normal cell and tissue features for developing rodents is simple thanks to several detailed developmental atlases [7, 11, 12, 14, 15,84–86]. A full appreciation of histopathologic changes for developmental phenotypes often requires that the histogenesis of the lesions be explored by serial evaluation of embryos at several times (e.g. serial days). For example, cardiac defects that initially produce gross structural malformations and/or histopathological abnormalities and altered circulation in the heart may lead over time to secondary lesions in other highly vascularized organs such as liver (congestion followed by necrosis) and lungs (right‐sided congestion) ( Figure 5.16).

Figure 5.15 Comparison of variable lesion progression in three litters of wild‐type GD13.5 mouse embryos at four days following maternal Zika virus infection. Several phenotypes are evident, and often cluster in particular litters. Acute death soon after exposure (based on conceptus size) resulted in embryonic resorption (as shown in the bottom row by small, oval, discolored implantation site remnants [arrowheads with dotted lines]). Slightly later embryonic death led to diffuse embryonic necrosis or autolysis rather than resorption (indicated in the middle row by uniform pallor, the absence of a pigmented eye primordium, and indistinct body contours). Other embryos appear to be viable (based on their similar, age‐appropriate size and anatomic features), but some exhibit focal acute hemorrhage (arrowheads with solid lines) as either a delayed effect of the virus or more likely an artifact of slight trauma encountered during necropsy.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Pathology of Genetically Engineered and Other Mutant Mice»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Pathology of Genetically Engineered and Other Mutant Mice» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Pathology of Genetically Engineered and Other Mutant Mice» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.