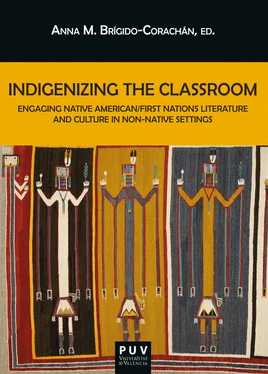

INDIGENIZING THE CLASSROOM

ENGAGING NATIVE AMERICAN/FIRST NATIONS LITERATURE AND CULTURE

IN NON-NATIVE SETTINGS

BIBLIOTECA JAVIER COY D’ESTUDIS NORD-AMERICANS

https://puv.uv.es/biblioteca-javier-coy-destudis-nord-americans.html https://bibliotecajaviercoy.com

DIRECTORA

Carme Manuel

(Universitat de València)

INDIGENIZING THE CLASSROOM

ENGAGING NATIVE AMERICAN/FIRST NATIONS LITERATURE AND CULTURE

IN NON-NATIVE SETTINGS

Anna M. Brígido-Corachán, ed.

Biblioteca Javier Coy d’estudis nord-americans

Universitat de València

Indigenizing the Classroom: Engaging Native American/First Nations

Literature and Culture in Non-Native Settings

© Anna M. Brígido-Corachán

1ª edición de 2021

Reservados todos los derechos

Prohibida su reproducción total o parcial

ISBN: 978-84-9134-748-4

Imagen de la cubierta: Navajo Ye'ii Tapestry Ca. 1920-30. Wool, 61 x 92.

Collection of the McNay Art Museum, Bequest of Marion Koogler McNay

Diseño de la cubierta: Celso Hernández de la Figuera

Publicacions de la Universitat de València

https://puv.uv.es

publicacions@uv.es

Edición digital

Contents

Reframing Our Pedagogical Practice.

Teaching Native American/First Nations Literature and Culture through Indigenous-centered Methodologies

ANNA MARIA BRÍGIDO-CORACHÁN

Pedagogies of Language Sovereignty

PHILLIP H. ROUND

Addressing Matters of Concern in Native American Literatures: Place Matters

CHRIS LA LONDE

Buffalo Man: Human-Animal Transformations in American Indian Fiction and Its Reception by Polish University Students

GABRIELA JELEŃSKA

An Interdisciplinary Approach to Teaching Pocahontas

TERESA GIBERT

‘With them was my home’: The Politics of Native Space in A Narrative of the Life of Mrs. Mary Jemison

ELENA ORTELLS

Teaching Native American Literature in Argentina

MÁRGARA AVERBACH

Native American Children’s Literature in the English Language Education Classroom

DOLORES MIRALLES-ALBEROLA

Indigenizing Afroperipheralism in Wayde Compton’s The Outer Harbour

VICENT CUCARELLA-RAMON

Identity (and Other) Lessons: Creative Writing in the Classroom as a Door into the Poetry of Ralph Salisbury

INGRID WENDT

Acknowledgments

This collective volume hopes to add to the growing discussion of Native American writing and critical pedagogies in the classroom. The idea to put this collection of pedagogical experiences, theories, and proposals together came after my participation in several international conferences (American Indian Workshop Resurgence and Resistance , London 2017, Small/Minor Literatures and Cultures: A Preliminary Debate , Santiago de Compostela 2017, and Teaching and Theorizing Native American Literature as World Literature , València 2018), and was inspired by the enlightening conversations held with many colleagues working in the field of Native American/First Nations and ethnic literary studies outside the United States and Canada. The challenges of teaching Indigenous American literatures in a foreign, non-Native setting are certainly greater for some of the reasons tackled in the chapters that follow. I would especially like to thank Ewelina Bańka, Silvia Martínez-Falquina, Gloria Chacón, Joanna Ziarkowska, Robert E. Lee, Gordon Henry Jr., David Moore, Kate Shanley, Sharon Holm, Rebecca Tillett, Aitor Ibarrola, César Domínguez, Susana Bautista, Sue P. Haglund, and Juan G. Sánchez for the inspirational exchange of ideas and classroom stories on Indigenous-centered theories and pedagogies and also thank Belén Vidal, María del Pilar Blanco, and Ana Fernández-Caparrós for their academic support and friendship. I am also most thankful, of course, to the amazing contributors to this volume for sharing their pedagogical experiences and wisdom with such commitment and passion.

An immense debt of gratitude and appreciation is also owed to my colleague, mentor, and friend, Carme Manuel—an extraordinary editor and a continuous source of inspiration in the classroom. This book would not have been possible without her insightful advice, generous assistance, and constant support, as well as that of the Conselleria d’Innovació, Universitats, Ciència i Societat Digital (Generalitat Valenciana), which provided funds for our research project “Las literaturas (trans)étnicas norteamericanas en un contexto global: representaciones, transformaciones y resistencias” (Ref. GV/2019/114).

Lastly, I would like to express my warmest gratitude to my students for their enthusiastic reception of Native American literary works throughout the years, in New York University and at the University of Valencia and, most dearly, thank my wonderful family—my parents, my partner Alex, and my precious children—for their unconditional love, patience, and emotional support.

Reframing Our Pedagogical Practice

Teaching Native American/First Nations Literature and Culture through Indigenous-centered Methodologies

Anna Maria Brígido-Corachán 1

Universitat de València

There will be no balance

without all voices present in the power circle.

Joy Harjo, An American Sunrise

In the past four decades Native American/First Nations Literature has consolidated itself as a literary and academic field and it is now read, taught, and theorized in a variety of educational settings outside the United States and Canada. Native North American texts have also broadened their themes and readership by exploring transnational contexts and foreign realities, and also through translation into major and minor languages, thus establishing creative networks with other literary communities around the world. However, when Native texts are taught in foreign contexts, the reproduction of Indian stereotypes, mystifications, and misconceptions is still a major issue that non-Native readers, students, and teachers continue to struggle with. This is even more the case in non-US/Canadian settings, where direct contact with contemporary tribal cultures and practices is non-existent and where constant exposure to cliché representations of Indians in popular culture (through mainstream films, books, cartoons, advertisements, toys, sports mascots, etc.) may lead students to believe that Indigenous cultures in 21 stcentury North America have either vanished or are circumscribed to dystopic, alcohol-ridden reservations.

When teaching Native American/First Nations literature, history, and culture in Spain, lecturers face an additional set of challenges that add to the potential misunderstanding, appropriation, mystification, and prejudice that commonly arises in non-Native classrooms in North America: students are no longer familiar with mainstream cultural references featuring Native communities and individuals in literature, films, or TV. They have never seen a western, an episode of The Lone Ranger and Tonto , or a Washington Redskins football game on TV. Their personal interests have shifted to other areas, channels, and formats such as social media or video games, while their cultural references have broadened and now include global cultural products such as K-Pop, reggaeton, or Turkish soap operas, with North American output quickly losing its dominant share of the cultural market.

When asked to imagine and describe an Indian , millenials and post-millenials in Spain have vague associations that reduce Native cultures to feathers and moccasins, teepees, buffaloes, and to (Disney’s) Pocahontas. A student or two in each classroom may be able to identify colonial realities and themes such as settler occupation, tragedy, and genocide or may mention Christopher Columbus’s historical error that led to the agglutination of extremely diverse Indigenous cultures under the false colonialist category Indian . But our students at the University of Valencia, for example, are rarely able to identify more modern stereotypes and areas of concern such as alcoholism and trauma, casinos, New Age shamans, social and environmental racism, political sovereignty, or cultural appropriation. In a way, it is perhaps best that their imaginaries are limited to romanticized lore (Disney’s Pocahontas is still a feminist model for many of our female students) because it reduces the number of clichés that must be interrogated. However, filling all of our students’ cultural and historical gaps in one semester (or a monthly unit!) while they read Native literary texts and Indigenous-centered scholarship is certainly a daunting task.

Читать дальше