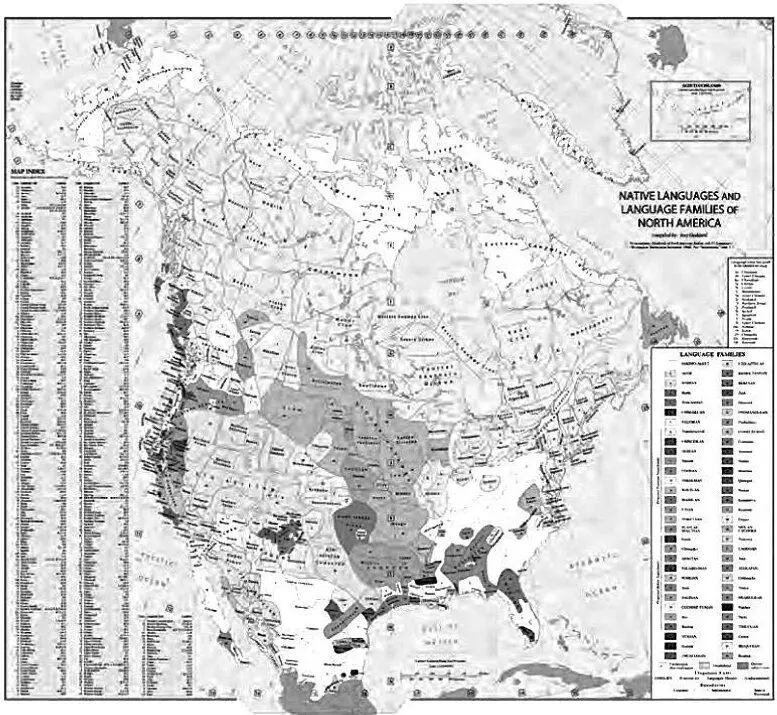

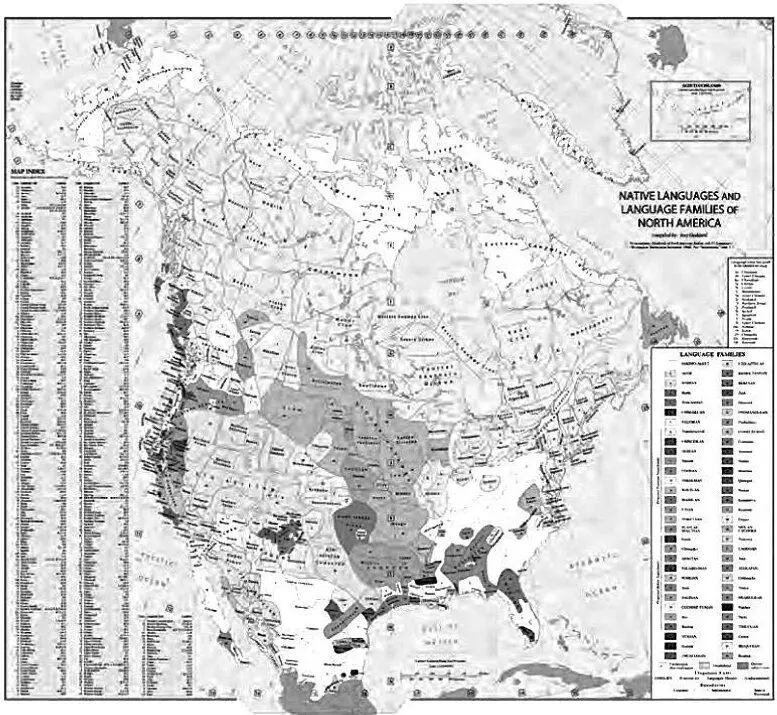

Thus, the first step in teaching Native literature from a language sovereignty perspective is to present students with a linguistic map of the US. This one, produced by the linguist Ives Goddard of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, vividly illustrates the many different kinds of languages that are at work in Indian Country.

Before European contact with North America, more than 300 separate languages were being spoken in this part of the Western Hemisphere. As ethnolinguist, Marianne Mithun explains, these languages were “mutually unintelligible … and differ in fascinating ways not only from the better-known languages of Europe and Asia, but also among themselves” (1). Whereas European languages can be categorized into only three distinct “families” (Indo-European, Finno-Urgic, and Basque), there are about fifty Indian language families in North America, none written in alphabetic form.

Among this linguistic diversity, several factors stand out as perhaps influencing the way Native writers approach writing in English. Words, for example, are treated differently in the polysynthetic languages of North America. In Yupik, a language spoken in western Alaska, the word kaipiallrulliniuk is translated into the English phrase “the two of them were apparently really hungry” (Mithun 39). Some North American languages like Mohawk contains only nine consonants, while Tlingit, an Athabaskan language, contains forty-five. In addition to diction and phonological differences, Native languages exhibit (as perhaps do all languages) some relationship to their physical environment. 3If one looks at the Goddard map and locates the landscape in which Yupik is spoken, it makes sense that this language is filled with terms like caginraq (“skin or pelt of caribou taken just after the long winter hair has been shed in the spring”), a term whose specificity is born of generations of experience in Alaskan ecosystems (Mithun 37).

Map by Ives Goddard. “Native Languages and Language Families.” Compiled for Languages, vol. 17 of the Handbook of North American Indians (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1996). 4

By examining this map, our students might also begin to imagine some other relationships that obtain between the land and language. Putting aside for a moment those many tribes that were removed from their homelands after the Indian Removal Act of 1830, 5 they might look at how the languages of the Athabaskan Family are distributed across North America. The swirl of olive color that denotes Athabaskan—split as it is between the sub-arctic and the Great Basin of the US—suggests another important element of language, the fact that it also maps migrations and movements of peoples.

In order to ground these somewhat speculative observations in the real-world work of a Native poet, let’s examine a writer whose community still resides in part of its original homeland and whose language speaks of that land. Jeanette Armstrong is Okanagan. Okanagan is spoken in southern British Columbia in Canada and in north central Washington in the US (Mithun 492). It is a language known to its speakers as Nsilxin , and is perhaps spoken by 500 to 1000 speakers. Armstrong is of the “opinion that Okanagan, my original language, constitutes the most significant influence on my writing in English” (178). She also believes strongly that “the language spoken by the land which is interpreted by the Okanagan into words, carries parts of its ongoing reality” (178). “In this sense,” Armstrong writes, “all indigenous peoples’ languages are generated by a precise geography and arise from it” (178). In addition to the “landed” nature of indigenous languages that lie behind Native writer’s English literary works, Armstrong notes a profound difference in the way that nouns and images are understood and employed in Okanagan.

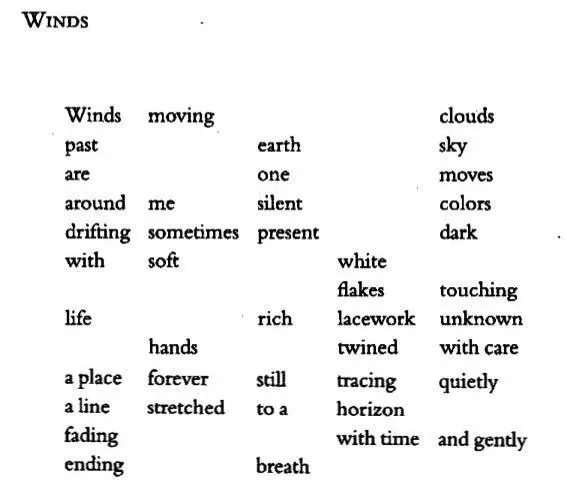

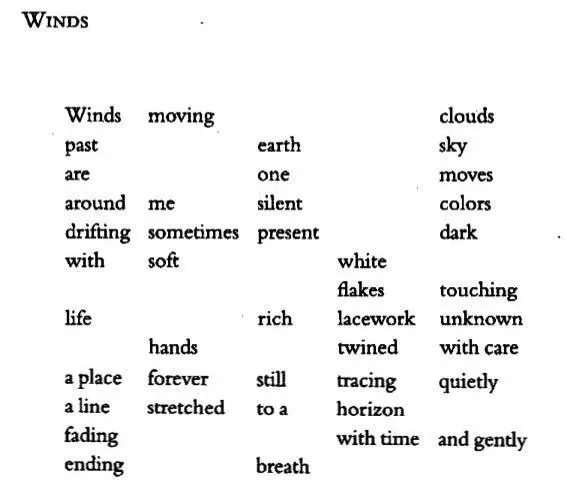

Using the example of the English word, dog , Armstrong explains, “when you say the Okanagan word for dog ( kekwep ), you don’t ‘see’ a dog image, you summon an experience of little furred life” (190). This is because the two syllables in the word suggest a combination of “a happening and a sprouting profusely (fur).” Armstrong thus observes that “speaking the Okanagan word for dog is an experience ” (190). In Okanagan, the word is more a verb than a noun, and when Armstrong employs this understanding to her English language works, “[she] attempt[s] to construct a similar sense of movement and rhythm through sound patterns” (192). In the poem “Winds,” she demonstrates these practices:

The influence of the Okanagan language on Armstrong poetry does not stop with these morphological and syntactic elements. The way English is spoken on the Okanagan Reserve is considered a kind of dialect of the English language that, in its various forms, is known in Indian Country as “Rez English.” Like Armstrong’s poetic lines in English, “Okanagan Rez English has a structured quality semantically and syntactically closer to the way the Okanagan language is arranged,” and Armstrong argues that “Rez English from any part of the country, if examined, will display the sound and syntax pattern of the area.” Armstrong explains how this might work in the following sentences:

Trevor walked often to the spring to think and to be alone. Rez English would be more comfortable with a structure like this: Trevor’s always walking to the spring for thinking and being alone. The Rez style creates a semantic difference that allows for a fluid movement between past, present, and future. (193)

In both her Rez English usage and her ethnopoetic approximations of Okanagan verbal arts structures, Jeanette Armstrong feels her “writing in English is a continual battle against the rigidity in English” (194).

If we turn our attention to a very different landscape and language located on the southern border of the US, we find the Tohono O’odham Nation and the poetry of tribal member and linguist Ofelia Zepeda. Two of Zepeda’s poetry collections, Ocean Power (1995), and Jewed I Hoi (2005), are bilingual O’odham/English gatherings of verse. Many of Zepeda’s poems “originated in the O’odham language,” and when she offers an English counterpart, she cautions the reader that “they are not translations of the O’odham into English” ( Jewed 7). As Zepeda explains in the Introduction to Jewed I Hoi , “Written O’Odham is a relatively new phenomenon,” and employs the orthography developed in the middle of the twentieth century by Albert Alvarez and Kenneth Hale.” Sanctioned by the O’odham Nation, “it is the writing system most commonly used for classroom teaching. Literacy in the O’Odham language is accessible only to young people in schools that offer O’odham language classes, and to adults who make the choice of becoming literate” (7-8). Thus Zepeda’s O’odham language poems stand in a unique relation to the verbal traditions that lie behind them. A case in point is her use of traditional songs to bring the rain to her desert homeland as a jumping off point for these two versions of “Cloud Song:”

Ce: daghim ‘o ‘ab wu: sañhim.

To:tahim ‘o ‘ab wu: sañhim.

Cuckuhim ‘o ‘ab him.

Wepeghim ‘o ‘abai him.

Greenly they emerge. In colors of blue they emerge.

Whitely they emerge.

In colors of black they are coming.

Читать дальше