Reddening they are right here.

As in Armstrong’s verse, the O’odham language exerts a special morphological influence on its English counterpart. The repetitions of word ending auxiliaries common in O’odham must be abandoned in the English version to emphasize what is the “experiential” nature of nouns in the vernacular. 6 Adverbial phrases shape the lines of the second version, adding a fifth where there is none in O’odham. It is a choice that sacrifices the medial caesura/half-line of the O’odham song, but one that Zepeda feels is necessary to capture the movement, what Armstrong called “the experiential” nature of traditional verbal art. Using just these two bilingual poets, an instructor could do a good job of making the students aware of the linguistic and aural elements so central to Native poetry.

If we consider Native American prose narrative, similar pedagogical opportunities apply. Take, for example, Black Eagle Child (1995) Ray A. Young Bear’s autobiographical novel that is largely written in verse-like short lines. 7 Young Bear, a member of the Meskwaki and Sauk Nation of the Mississippi, describes the work as “a creative emulation,” one that he believes is both a continuation of traditional storytelling, “word collecting,” and vision and healing practices, as well as a “divergence,” and a necessary transformation pressed on him by the “dynamic trends” of twentieth-century language use (both vernacular and English) by the “bilingual/bicultural worlds [he] lives in” (254). Like Zepeda and Armstrong, Young Bear is wary of relying on mere translation to ground the aesthetic of indigenous literature. That is because, for Young Bear, “the poetic forms I have adopted and adapted (from English, a second language) have little significance in the tribal realm” (253). The tribal writer’s work, in Young Bear’s mind, is a profoundly ambivalent one. In it, the artist must steer a precarious course between speaking that which is never to be spoken to outsiders and yet collating the story worlds of his community into something viable for the situation in which the People of the Red Earth (Meskwaki) find themselves today.

Moreover, Young Bear views the hegemonic nature of the English language as at the heart of many of his community’s social problems, which he fictionalizes in the novel. In order to subvert this kind of English language usage, Young Bear allows his narrator to satirize the acronym-laden language of the US government and the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Speaking of his fellow tribal members as “separated from each other by infinite miles,” the novel’s protagonist comments,

We sought and expected a grain of civility

In our people, regardless of who they were.

And while we all recognized the lineage abbreviations

Got out of hand, we all resided in the same

Hellhole. Provided no one made waves—be it

And EBNO, and EBNAR (Enrolled But Not A Resident),

BRYPU (Blood Related Yet Paternally Unclaimed),

UBENOB (Unrelated By Either Name Or Blood),

EBMIW (Enrolled But Mother Is White),

And so forth—a sense of decency and harmony

Was possible . . . (98)

By far, however, Young Bear’s most common approach to battling the linguistic hegemony of outsiders is his code switching from Meskwaki to English. Early in the novel, as the protagonist, Edgar Bearchild, and his closest friend, Ted Facepaint, speed around the tribal community with two other Indian friends from different nations, they toggle back and forth between Meskwaki and English:

Ted Turned on the single headlight and wipers

And pretended to strain for a look.

‘ A sa mi win a ni . That’s too much.’

‘I know,’ I said, breaking into English

For the benefit of the Ontarios.

I was going to translate what I had just said,

But Ted sensed my plans and cut me off.

‘ E ye bi me a tti mow a nit e bi ke me ko

A ski ki wa sqwe se a wi ta bi ma ta .

Before you say anything, the girl you

Are sitting with is quite young.’

‘ Ohhn, ke te na ? Oh, is that so?’

‘And she also desires you.’

‘ Ke ne tti ma a bebe tte tti .

You are such a liar.’

Ted and Edgar’s bilingual banter exemplifies the kind of linguistic play that Keith Basso defined as “code switching” in Native verbal performances: “language alternations . . . [that] may be strategically employed as an instrument of metacommunication . . . an indirect form of social commentary” ( Portraits 8-9).

Another significant element of Young Bear’s approach to writing out the Meskwaki vernacular lies in his use of the Great Lakes Syllabary, an alphabetic shorthand for writing Native languages that emerged in the Great Lakes during the nineteenth-century and is known to the Meskwaki as “ Pa-pe-pi-po .” Such syllabaries, like the more famous one invented by the Cherokee tribal member, Sequoyah in the 1820s, embody deeply felt cultural practices that went far beyond mere translation. In fact, “encoding spoken [vernacular] into written form involves, not only a set of letters, but a set of spelling conventions also; and these last can best be described as an ordered set of context restricted rewrite rules” (Walker 404).

The Laguna Pueblo writer Leslie Silko also provides an excellent source of teaching hybrid literary materials that highlight linguistic sovereignty. In the most recent edition of Storyteller (1975; 2007), for example, Silko explains why the original version of the book was formatted along a horizontal, rather than vertical axis:

The shape of Storyteller was unusual because I wanted to give plenty of space to the poems I’d written on paper turned sideways for increased width. I experimented with using space on the page, with indentations and various line spacings to convey time and distance and the feeling of the story as it was told aloud. (xxvi)

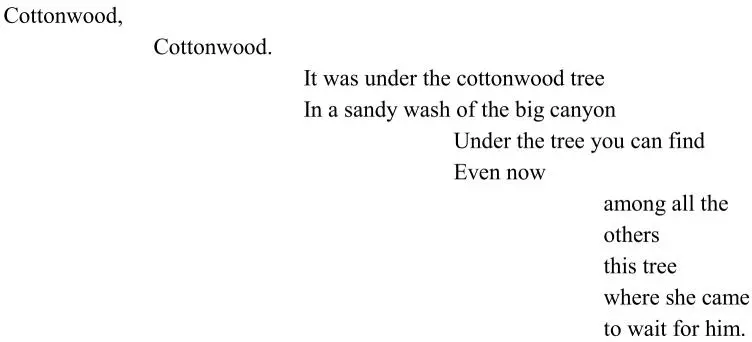

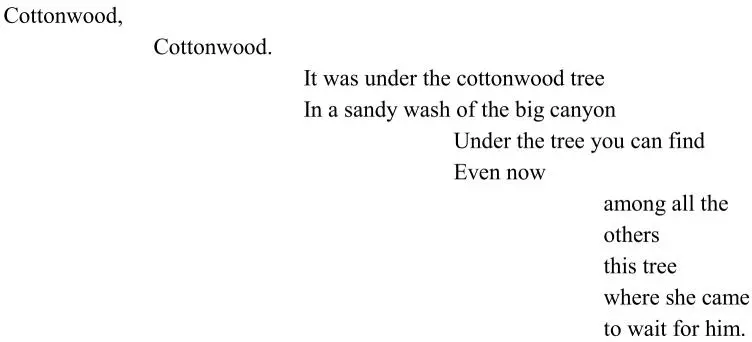

In the poem, “Cottonwood,” for example, Silko not only covers the entire wideformat page, but also employs non-standard stanza forms that similarly “convey time and distance:”

The poem branches like a cottonwood tree, projecting from a canyon wall, as they do in Pueblo country, and as is pictured in one of the photographs included in the collection. But “Cottonwood” isn’t just a “poem.” It is also a traditional story, and the formatting Silko uses in the rest of this passage suggests another important language sovereignty gesture that is centered on the way that Silko seeks to bring her community’s and family’s stories into the reader’s present through spatial and diacritical techniques that foreground intersubjectivity, language loss, and language recovery. In “Cottonwood,” this technique appears in the above passage through Silko’s use of parenthetical commentary on the actual identity of the human being who meets the woman “in the sandy wash of the big canyon.”

where she came to wait for him.

‘You will know,’

He said,

‘you will know by the colors—

cottonwood leaves

more colors of the sun

than the sun himself.’

(But you see, he was the Sun,

He was only pretending to be a human being.)

Silko employs such gestures towards intersubjectivity throughout the book. 8 In an early story from the collection, Silko retells her Aunt Susie’s tale of a little girl whose death yields an unexpected proliferation of butterflies in Pueblo country. Early in the story, the little girl asks her mother to make her a corn-meal porridge called yashtoah , and Silko takes this opportunity to enhance the intersubjective context of her work:

Читать дальше