BIBLIOTECA JAVIER COY D’ESTUDIS NORD-AMERICANS

The Slave’s Little Friends: American Antislavery Writings for Children © Carme Manuel

Este volumen se enmarca dentro del proyecto “La literatura infantil y juvenil de los Estados Unidos en el s. XXI: Análisis teórico y aplicaciones prácticas” (UJI-B2018-02) (2019-2021)

1ª edición de 2022

Reservados todos los derechos

Prohibida su reproducción total o parcial

ISBN: 978-84-9134-959-4 (papel)

ISBN: 978-84-9134-960-0 (ePub)

ISBN: 978-84-9134-961-7 (PDF)

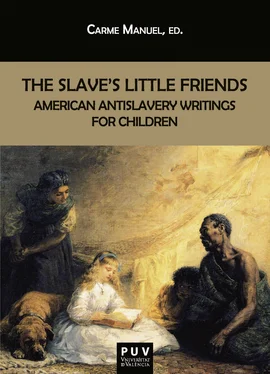

Imagen de la cubierta: Edwin Long, Uncle Tom and Little Eva (1866)

Diseño de la cubierta: Celso Hernández de la Figuera

Publicacions de la Universitat de València

https://puv.uv.es

publicacions@uv.es

Edición digital

A Nina

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

The Children’s Crusade: American Children’s Literature of Atrocity

AMERICAN ANTISLAVERY WRITINGS FOR CHILDREN

“OLD BETTY” (1823)

Margaret Bayard Smith

“THE NEGRO NURSE” (1827)

Isabel Drysdale

LIFE AND ADVENTURES OF OLAUDAH EQUIANO (1829)

Abigail Field Mott

“JUMBO AND ZAIREE” (1831)

Lydia Maria Child

“MARY FRENCH AND SUSAN EASTON” (1834)

Lydia Maria Child

From THE SLAVE’S FRIEND (1835-1839)

From JUVENILE POEMS: FOR THE USE OF FREE AMERICAN CHILDREN, OF EVERY COMPLEXION (1835)

William Lloyd Garrison

THE LIBERTY CAP (1846)

Eliza Lee Cabot Follen

THE ANTI-SLAVERY ALPHABET (1846)

Hannah and Mary Townsend

From THE YOUNG ABOLITIONISTS; OR CONVERSATIONS ON SLAVERY (1848)

Jane Elizabeth Jones

From COUSIN ANN’S STORIES FOR CHILDREN (1849)

Ann Preston

A PICTURE OF SLAVERY FOR YOUTH (184[?])

Jonathan Walker

PICTURES AND STORIES FROM UNCLE TOM’S CABIN (1853)

Harriet Beecher Stowe

THE EDINBURGH DOLL (1854)

Aunt Mary

From LOUISA IN HER NEW HOME (1854)

Sarah C. Carter

RALPH; OR, I WISH HE WASN’T BLACK (1855)

Harriet Newell Greene

From THE CHILD’S BOOK ON SLAVERY; OR, SLAVERY MADE PLAIN (1857)

Horace C. Grosvenor

“SELLING BABIES,” “A MOTHER IN PRISON” (1859)

Matilda Hamilton Fee

THE CHILD’S ANTI-SLAVERY BOOK, CONTAINING A FEW WORDS ABOUT AMERICAN SLAVE CHILDREN AND STORIES OF SLAVE-LIFE (1859)

“LITTLE LEWIS: THE STORY OF A SLAVE BOY”, Julia Colman

“MARK AND HASTY; OR, SLAVE-LIFE IN MISSOURI,” Matilda G. Thompson

“AUNT JUDY’S STORY: A STORY FROM REAL LIFE”, Matilda G. Thompson

“ME NEBER GIB IT UP!”, Anonymous

STEP BY STEP, OR TIDY’S WAY TO FREEDOM (1862)

Mrs Helen E. Brown

THE GOSPEL OF SLAVERY: A PRIMER OF FREEDOM (1864)

Iron Gray (Abel C. Thomas)

INTRODUCTION

The Children’s Crusade:

American Children’s Literature of Atrocity

But the day will come when the rod of the oppressor will be broken, and the slaves will go free. God has said it. Let us pray for that day, and work for it, and it will come.

The Slave’s Friend

Our contemporary world is the scenario of constant violations of human rights. Among their many manifestations, slavery remains a widespread social and political scourge, even though it is frequently transformed into barely visible, and consequently, more fluid types of human exploitation. “The current manifestations of slavery,” Claude E. Welch affirms, “are far more subtle than those of captured, racially-differentiated slaves imported into a society to fill specific labor needs, the form most familiar to Westerners. Slavery in the twenty-first century is deeply rooted in many societies, promulgated by existing norms, in which selected groups in the general populace are particularly liable to slave-like practices” (72). Experts on the field—Kevin Bales, Joel Quirk, among others—agree that, in spite of the efforts of the numerous worldwide human rights organizations, there are more than twenty million enslaved individuals (men, women and children) throughout both the most and the least developed countries. In his Unfinished Business: A Comparative Survey of Historical and Contemporary Slavery , Quirk argues for the implementation of four overlapping strategies to fight contemporary forms of slavery and slave-like practices: “i) education, information and awareness, ii) further legal reform, iii) effective enforcement, and iv) release, rehabilitation and restitution” (114). At the core of modern antislavery activism, public education is “one of the most effective ways of improving general knowledge of slavery” (115). Yet, primary, secondary and even university educational curricula continue to ignore the study of slavery at international and national levels. Most children and young people lack a fundamental knowledge of how the economic and political system of human bondage shaped past first-world empires and colonization ventures, and do not recognize the permanence of new forms of human exploitation in contemporary societies. If our educational institutions have not yet introduced the study of multifarious types of bondage as a mandatory requirement, how can twenty-first-century children be exposed to these economic, political and moral injustices? Do parents explain these abuses of human rights to their children? Do parents or tutors, across different ranges of political and ideological perspectives, introduce readings or encourage children to buy books showing how other children in remote parts of the world or in their own countries are exploited because of class, skin color, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation or disability? Are twenty-first-century children aware of the existence of slavery in the modern world? Do parents and educators make any effort to alert them about the thriving trade of human beings in our globalized societies? Do they know about “disposable” people? Do children read about human trafficking, indentured servitude, and lifelong servitude in the world? Claude E. Wench reminds us that “the elimination of all forms of slavery may also require significant changes in social attitudes” (77). How can we then enhance our children’s awareness, raise their political consciousness towards these forms of injustice that are perpetuated throughout time?

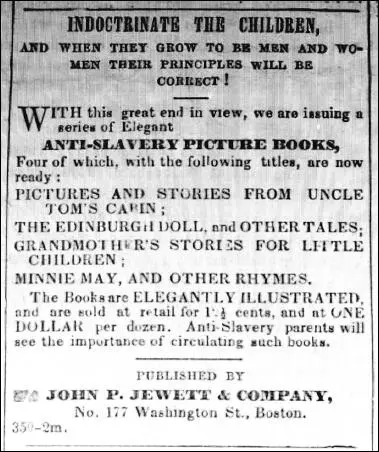

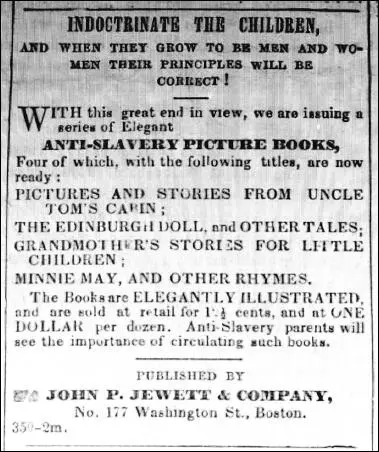

Taking into account contemporary parental and social attitudes, the advertisement that appeared in Frederick Douglass’ Paper (published in Rochester, New York) on October 13, 1854, may come as a provocative surprise 1: “INDOCTRINATE THE CHILDREN, AND WHEN THEY GROW TO BE MEN AND WOMEN THEIR PRINCIPLES WILL BE CORRECT.” Thus read the notice paid by John P. Jewett, the Boston publisher who had reached success for publishing Uncle Tom’s Cabin in book form two years before, and who was then trying to expand his series catering for potential young readers with antislavery picture books in the hope that “anti-slavery parents will see the importance of circulating such books.”

Jewett’s potential young readers in 1854, however, were not the first to have the experience of enjoying antislavery stories bought by antislavery parents. American children had had the opportunity to consume antislavery literature specifically written for them since the early decades of the nineteenth century. The works included in this anthology are a small example of the many texts written and published for children in the antebellum period. Writing about the possibilities of children’s literature in a post-holocaust world and borrowing Lawrence L. Langer’s coinage in

Читать дальше