The Holocaust and the Literary Imagination (1975), Elizabeth R. Baer asks if writers should create “literature of atrocity” for children (381) with themes that “illustrate the aesthetic problem of reconciling normalcy with horror” (381). American antislavery literature for children penned by male and female abolitionists and antislavery reformers attempted not to reconcile but to exhibit the flagrant contradictions between the American national republican ethos and the horror of the institution of slavery in an attempt to garner the little ones’ political response. “If you make children abolitionists slavery must come to an end,” announced a motto appearing in

The Slave’s Friend (3.2, 1838: 8), condensing the educational and political attitude sponsored by the authors featuring in its pages.

Margaret Bayard Smith, Isabel Drysdale, Lydia Maria Child, Hannah and Mary Townsend, Eliza Lee Cabot Follen, Jane Elizabeth Jones, Ann Preston, Jonathan Walker, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Sarah C. Carter, Harriet Newell Greene Butts, Abel C. Thomas and many other female and male American antislavery writers in the antebellum era seem to have been deeply convinced of three things. First, they understood the child to be the supreme representative of the national republican ethos; second, they thoroughly believed in the evil of slavery; and third, they radically defended literature as the path to raise children’s political awareness. As inheritors of the Enlightenment philosophical attitudes on childhood and educated in their infancy under the literary wings of well-known transatlantic luminaries of British children’s writing—John Newbery, Sarah Fielding, Anna Laetitia Barbauld, Thomas Day, Dorothy Kilner, Sarah Trimmer, Amelia Opie and Maria Edgeworth, among others, these American antislavery authors were conscious of the prominence of their efforts when contributing to the critique of the institution of slavery and the role that American children would consequently play in its demise. Yet, as Caroline F. Levander explains, these political texts call for a critical reading since the child constructed by their antislavery rhetoric “simultaneously works to eradicate slavery and to reinforce the enduring power of white supremacy to an audience anxious about the impact of emancipation on the nation and the racial order that has historically defined it” (2006: 50). Consequently, antislavery writings for children stand as highly controversial texts in their relation to historical truth. Even so, their praiseworthy attempts to engage their readers’ ethical and political understanding must be recognized as exceptionally significant when unearthing the cultural constructions of American children as liberal citizens of a racially segregated republic.

THE ENGLISH ORIGINS OF ANTISLAVERY LITERATURE FOR CHILDREN

The spectacular rise of children’s literature in the eighteenth century catered for a new conception of the child. Following the Lockean dictums of instructing and entertaining at the same time, John Newbery was the first to capitalize on this transformation. At the end of the century, as J.R. Oldfield explains, “equally resourceful competitors had sprung up in the shape of John Marshall, Vernor and Hood, John Stockdale, and Darton and Harvey” (143). These publishers initiated the industry of children’s literature in Great Britain and would set the pace for the transatlantic American world of juvenile works, which would readily expand throughout the nineteenth century.

English reformist movements were quick to grasp the relevance of children as a new potential audience as of the early eighteenth century. The Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was founded on May 22, 1787, by Granville Sharp, Joseph Woods, and Thomas Clarkson, among other Quakers, with the aim of promoting campaigns against slavery. To that end they encouraged writers and artists to support the abolition of the slave trade and the condemnation of slavery in the English overseas territories.

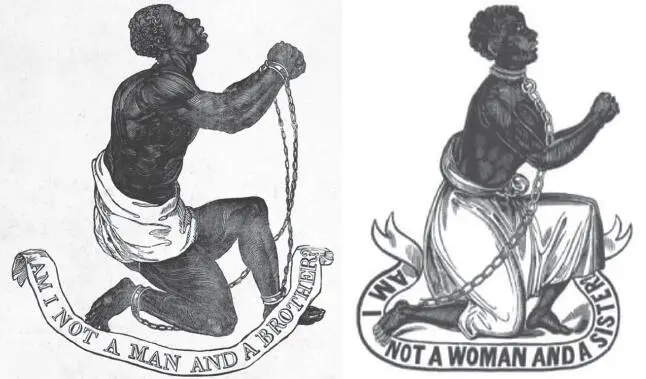

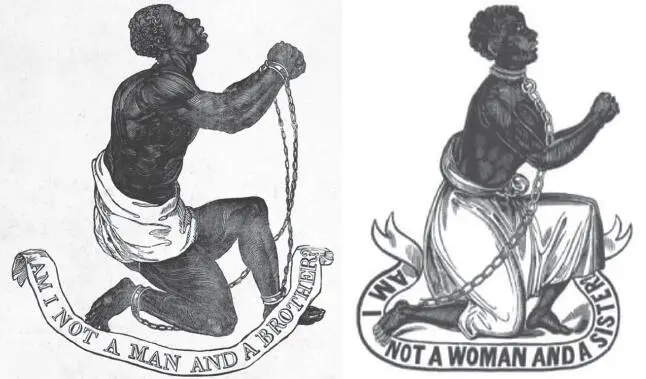

As the movement gained momentum, explicit visual elements were produced to show support as part and parcel of the growing antislavery material culture. Two of the most celebrated images—widely reproduced in transatlantic antislavery and children’s literature—were those appearing on Josiah Wedgwood’s medallions (first made in 1787 for the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade) portraying kneeling male and female slaves, with their chained hands and a pleading expression—“Am I not a Man and a Brother?” / “Am I not a Woman and a Sister?”

These images appealed to the head and the heart, to the sense and the sensibility of late-eighteenth-century Britons to such an extent that they became the unquestionable emblem of the antislavery struggle. As Marcus Wood explains, antislavery writings were profligate in their employment of imagery and they showed the “irrational belief that pictures speak for themselves in a way that words do not” (2000: 6). Thus, paintings, broadside woodcuts and photographs, among many other visual materials accompanying the written texts, must also be read and studied under harsh scrutiny. The appearance of the kneeling male/female slave on a number of everyday objects (plates, shoe buckles, coins, glasses), jewelry (medallions, hair pins, pendants), as well as in printed material (pamphlets, leaflets, books) is, consequently, not free from conflicting representational messages. Calling into doubt the exclusion from humanity and Christianity, some scholars believe that the noble slave does not pose any threat but merely interrogates the readers’/viewers’ sense of sympathy and beseeches benign inclusion into the human family. Yet, at the time these artifacts were issued, the question the kneeling slave posed was only apparently rhetorical, since it clearly asks for a reinterpretation of Africans as a separate species within the Great Chain of Being, as defended by pro-slavery Britons, as well as for recognition of sameness and, consequently, humanity.

Scholars have pointed out the ways in which sympathy became politicized during the first decades of the nineteenth century and how the visual materials accompanying antislavery and proslavery writings contributed to consolidate ideological responses. Albert Boime, Margaret Abruzzo, John H. Bickford and Cynthia W. Rich, Karen Halttunen, George E. Boulukos, Penny Brown, Brycchan Carey, Marcus Wood, among others, have written about the urgency to recognize that slavery was read about but also controversially envisioned. In Slavery, Empathy, and Pornography , Marcus Wood writes that the problem is how “to explain that the dirtiest thing the Western imagination ever did, and it does compulsively still, is to believe in the aesthetically healing powers of empathetic fiction” (36). Slavery facilitated the propagation of thousands of images that served the needs of late eighteenth- and nineteenth-century English and American readers for pathos but also for voyeurism. The pain of others visualized in images of defenseless sufferers promoted what Karen Halttunen calls “spectatorial sympathy,” a concept that was “instrumental in shaping the eighteenth-century literature of sensibility.” The immense corpus of fictional, dramatic, and poetic texts that subscribed to the ideas of sentimental art “undertook to teach virtue by softening the heart and eliciting tears of tender sympathy, an aim reinforced by eighteenth-century art criticism, which emphasized emotional response rather than rational judgment as the proper criterion for evaluation.” Countless scenes of tormented human beings and animals aroused readers’ and viewers’ sympathy and enhanced and demonstrated their virtue (307). For Halttunen, the gaze of free citizens “liberally mingled pleasure with vicarious pain,” delighting in a sort of “dear delicious pain,” “a sort of pleasing Anguish” (308)—condemned by Keats as an “aching pleasure”—that bordered on the pornographic. Consequently, “reform literature did eroticize pain, constructing it as sexual in nature. The eroticization of suffering in humanitarian reform sometimes took the form of overtly sexual references: to the ‘indecent’ nudity and sexual abuse of idiot or insane women, to the sexual coercion and rape of slave women […] Their treatment of scenarios of suffering, if not narrowly pornographic in nature, assumed that the spectacle of pain was a source of illicit excitement, prurience, and obscenity—the power to evoke revulsion and disgust” (324-325). For her part, Marianne Noble also asserts that the exhibition of the tortured body of the enslaved brought about a “sentimental wounding” that placed the slave as “erotic objects of sympathy rather than subjects in their own rights” (296).

Читать дальше