There are many good people in England; why do they not strive to stop such cruelties? I am glad to have it in my power to say that a great number of tender minded people, both in America and England have set their slaves at liberty. Others have been using their endeavors for years past, and not without some good success; to abolish a trade so big with numberless evils, some hundreds of slaves have been liberated in divers parts of America.

In 1800 both volumes were published under the latter title. As Linda David explains, “the antislavery passage in the second volume was expanded in 1800 to include references to the poetry of Phillis Wheatley and the letters of Ignatius Sancho—surely the very earliest mention of these black writers in a children’s book” (16). 2Darton’s Little Truths “demonstrated the speed with which the growing literature on the slave trade, much of it collected and published by the London Committee and enthusiasts like Thomas Clarkson, reached juvenile readers” (Oldfield 144).

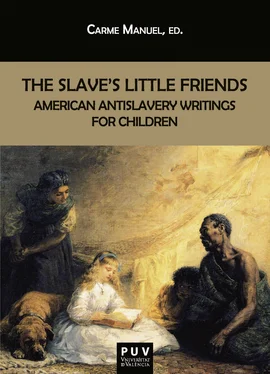

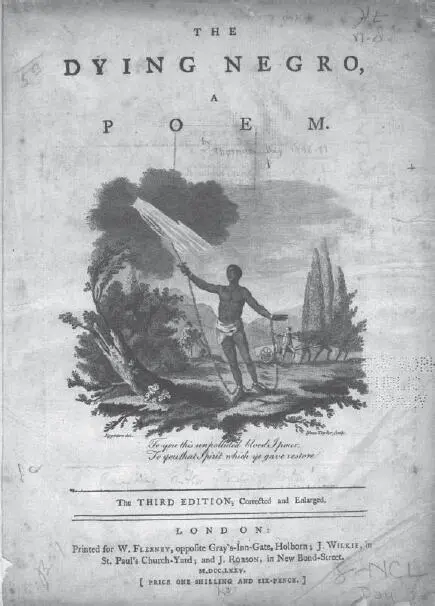

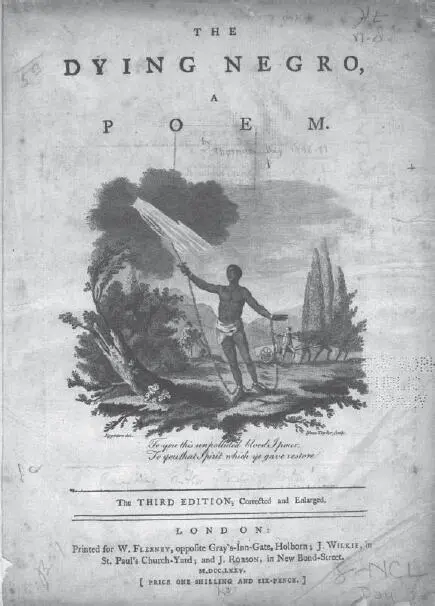

English publishers and writers were willing to join the antislavery movement and rapidly participated in the criticism against the slave trade and the evil institution by including black characters in their tales. One of the most celebrated examples appears in Thomas Day’s The History of Sanford and Merton (1783-89), where a black beggar rescues Harry Sanford from a dangerous bull. The story offers a romanticized view of African tribal life, where Africans are depicted as black Rousseaunian noble savages brutally snatched away from their land and innocent families. In 1773, Day had co-authored with John Bicknell “The Dying Negro: A Poetical Epistle,” the piece considered to be the first significant antislavery poem, although for an adult audience.

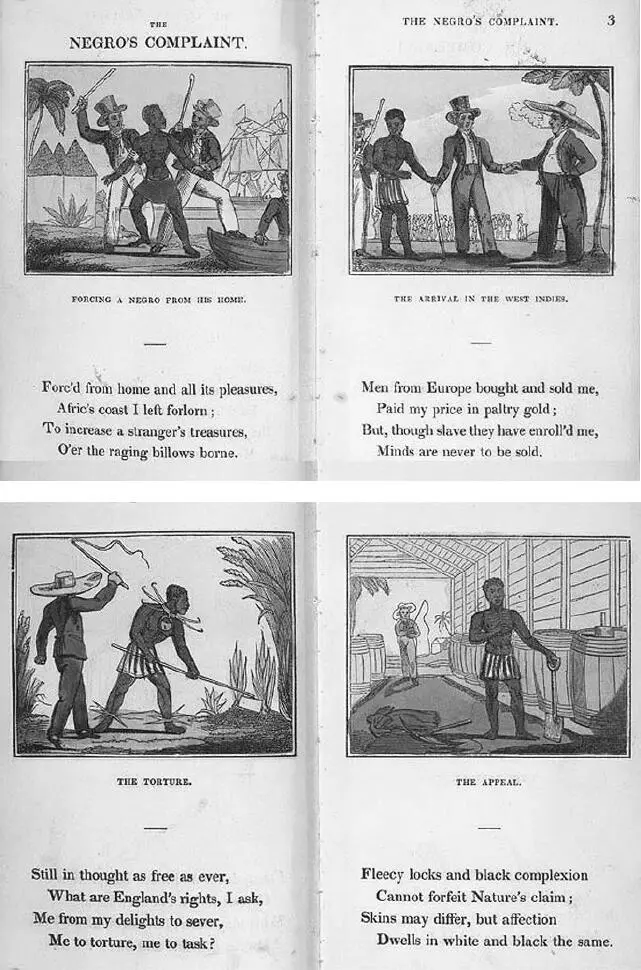

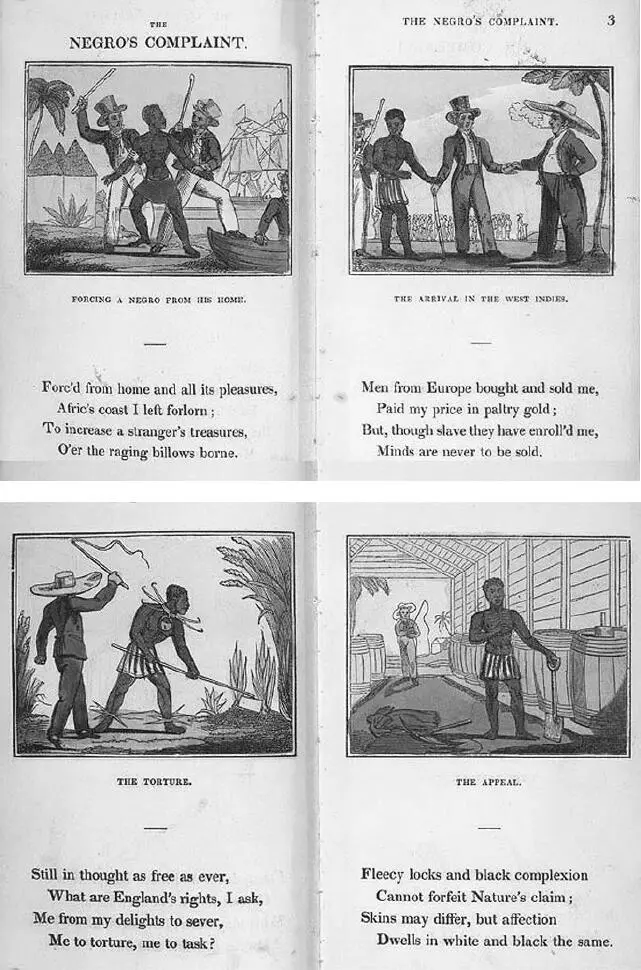

In 1788 William Cowper published “The Negro’s Complaint,” an antislavery poem that became so extremely popular that it was turned into a ballad. Harvey and Darton published a children’s version with another poem titled “Pity for Poor Africans” ( The Negro’s Complaint: A Poem. To Which is Added, Pity for Poor Africans ), with colored woodcuts, in 1826. The book made use of the same visual layout as other contemporary antislavery volumes — Amelia A. Opie’s The Black Man’s Lament, or How to Make Sugar (1826) — with an illustration and poetry stanzas underneath them on each page. Cowper’s poem appeared in the wake of the initial sugar boycotts in Britain and was widely distributed by the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Elizabeth Massa Hoiem explains that this reprint “uses popular generic conventions for teaching children about commodities,” which have been called It-narratives, to give agency and voice to personified commodities. Yet, here the narrator is an enslaved African who tells his own story. Cowper’s antislavery poems were widely reprinted and distributed in newspapers and magazines in the transatlantic English world and had a significant impact on the English campaigns against the slave trade as well as on American abolitionist writings.

John Aikin and his sister Anna Laetitia Barbauld also turned to black characters in some of their stories in their six-volume series Evenings at Home; or, The Juvenile Budget Opened Consisting of a Variety of Miscellaneous Pieces for the Instruction and Amusement of Young Persons (1792-1796), a miscellany of tales, fables, poems, and dialogues, which epitomize the tenets of the educational principles of the Enlightenment. These black characters “brought immediacy and authenticity to the antislavery struggle, and the device was widely imitated” (Oldfield 144).

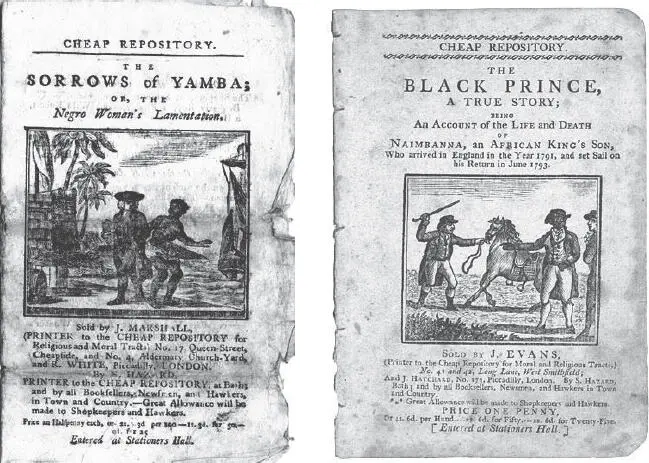

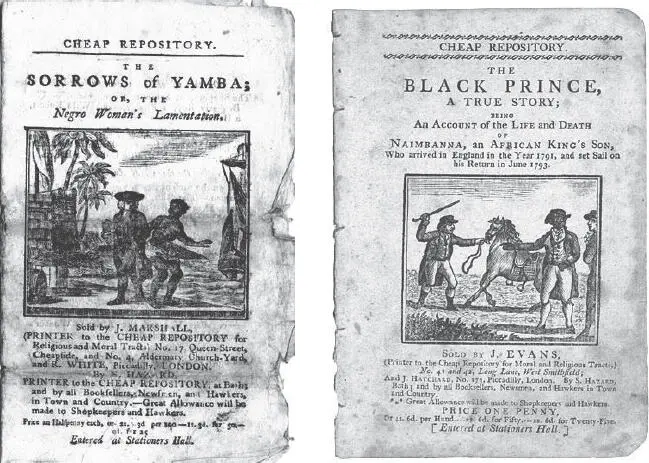

In 1795 Hannah More published The Sorrows of Yamba; or, The Negro Woman’s Lamentation in her Cheap Repository Tracts series. More was a member of the Clapham Sect, a group of leading Evangelical reformers devoted to social reform, and her Tracts were written to instill the need to abolish the slave trade and slavery among children and adults. More’s sole authorship of the poem has been questioned and some historians believe that the piece was originally penned by the Scot Eaglesfield Smith. The Sorrows of Yamba tells the story of an African woman kidnapped and sold as a slave who suffers the death of her child on her sea voyage. Devastated by her loss, she tries to commit suicide but meets a missionary who converts her to Christianity. Her new religious beliefs help her reconcile herself with her captors and wish for her husband’s conversion to the new faith in Africa. The poem became one of the most popular and reprinted antislavery poems of its time, together with The Black Prince (1796), a poem she did not write but, according to Robert Hole, “was published under her editorship” (619). The story was a true account of the visit of Naimbanna, ‘An African King’s Son,’ to England between 1771 and 1793, to engage British help to found a colony of freed slaves in Sierra Leone and “insisted on the equality and equal rights of all ‘whatever be their colour’ and on the dignity and nobility of the black person” (619). As Hole and other critics point out, More viewed Africans as unequal to white British citizens since her position was determined by a Christian faith that rested heavily on a providential hierarchy, product of her times and of the racial ideologies of Anglican evangelical abolitionists.

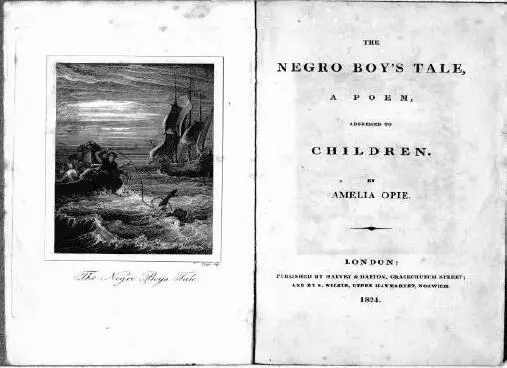

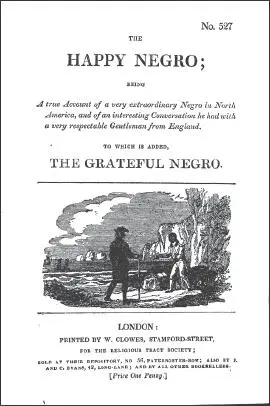

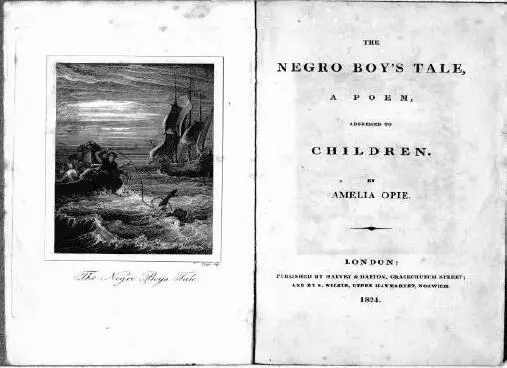

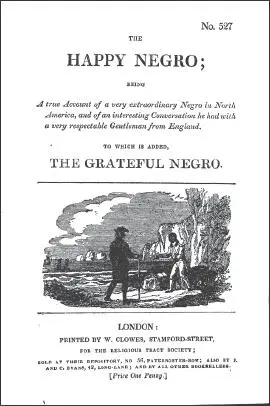

In 1801, the Quaker novelist and poet Amelia Opie published “The Negro Boy’s Tale: A Poem Addressed to Children,” included in the first edition of The Father and Daughter . In 1824, Harvey and Darton reissued the poem in volume form as part of the antislavery series for children. In 1804, three years before the abolition of the slave trade in Britain, Maria Edgeworth published her tale, “The Grateful Negro,” which had at least five American editions (1804-1813, 1823, 1832, 1835). In the same year Priscilla Wakefield, an important and prolific author of children’s geography books, published A Family Tour through the British Empire , where she included some thoughts on the trade when the family visits the port of Liverpool:

As they had never been on board a ship, the opportunity was too inviting to be neglected; they entreated their mother to mention their wish to Mr. Franklin, who readily accompanied them to several of different forms and dimensions. The disposal of the apartments; the contrivances for accommodation in so small a space; and the manner of stowing goods; with the sails, masts, and rigging, the uses of which were explained by their kind instructor; not only amused them, but furnished their minds with a new set of ideas. In reply to Edwin’s enquiry, In what consists the chief trade of Liverpool? Mr. Franklin remarked that it is the second port in the kingdom, and is frequented by ships from most parts of the world. “Its foreign commerce,” said he, “is very extensive and profitable; but it is sincerely to be lamented, that one branch of it is contrary to humanity and justice: I mean that of trafficking to Guinea for slaves, whom they carry, against their inclination, to the West Indies, and then barter them for sugar, rum, cotton, and other produce.” His companions, uncorrupted by prejudice or interest, warmly declared their abhorrence of buying and selling their fellow-creatures, and were surprised that any person, who pretended to a virtuous character, would obtain a fortune by such unjust means. (55)

Читать дальше