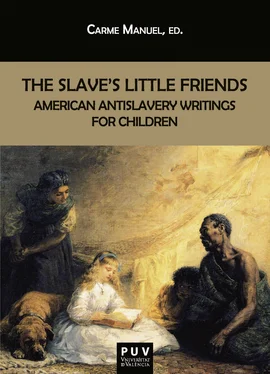

In The Illustrated Slave: Empathy, Graphic Narrative, and the Visual Culture of the Transatlantic Abolition Movement, 1800-1852 , Martha Cutter (10-11) distinguishes between “parallel empathy” and “hierarchical empathy” as the two strategies that explain how readers and viewers reacted to these literary and graphic materials, modes that can coexist within the same written or visual text. For this scholar, “the mode of empathy most common in abolitionist artwork and visual texts relies on hierarchy: the idea that the pained body and psyche of the enslaved is a low, unfinished, disabled, childlike, or in some way inferior entity that needs the help and mediation of the white viewer, who is separated within the text or artwork from the viewed. This hierarchical mode of empathy relies on a viewer’s pity for the enslaved, who possesses only an unfinished and open selfhood, rather than the finished and closed selfhood of the viewer” (11). In contrast to this mode of hierarchal empathy, Cutter explains that parallel empathy “relies on similarity between the enslaved person and the viewing subject; the enslaved person is seen as a conspecific, and the connection between the self and the other is emphasized over figuration of division and difference. The viewer and the enslaved are brought into some degree of concordance by this mode of parallel empathy” (11).

In the early illustrated antislavery writings this mode prevailed, claims Cutter, because it was thought to move “the viewer beyond receptivity to another’s pain (common in hierarchical empathy) toward specific, tailored helping actions (such as stopping a whipping) or larger, prosocial ones (for instance, joining an abolitionist movement or becoming part of the Underground Railroad)” (11). The viewer/reader is asked not to “feel pity” for the body in pain but to see “a self that could also potentially be whipped, tortured, or emotionally traumatized” (11). The American abolitionist writings for children included in this anthology aimed at this mode of parallel empathy. Children are constantly stimulated to reflect on themselves and on the possibilities of their taking the place of the enslaved, and not only to enjoy the pathetic and voyeuristic spectacle of slavery and its atrocities. At the same time, they are encouraged to go beyond the written and the visual to imagine what is veiled by words and images.

The Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade also had women amongst its participants. It was an organization made up primarily of men, but its subscribers included many Quaker women who, throughout the 1780s and 1790s, supported and campaigned for its causes. Moira Ferguson coined the term “Anglo-Africanism” to refer to writings about Africans, a term that echoes Edward Said’s deployment of ‘Orientalism’ as a concept that includes Western views of the East, and explores the connections between feminism and abolitionism to demonstrate how in their antislavery writings British women projected their anxieties about their own oppressed status onto their literary constructions of slaves. Anglo-Africanist writings, Ferguson states, show how pro-antislavery white female authors gendered their abolitionist arguments and centered on the domestic sphere (the disruption of family bonds and sexual abuse) while they silenced the voices of slaves and described them as passive victims of physical and spiritual exploitation.

From their domestic sphere women politicized their role through calls for antislavery resistance and issues such as the boycott of sugar derived products (what was called “abstention”) were seen “from the first as a particularly female concern, and it provided women with another important opportunity to actively participate in the abolition campaign,” as Clare Midgley explains (35). For example, Mary Birkett, a Dublin Quaker, published “A Poem on the African Slave Trade: Addresses to her Own Sex. In Two Parts” (1792). Midgley writes that Birkett’s “poetic appeal called on women not only to exert their influence on men but also to take action themselves by abstaining from slave-grown sugar” (35). Women working outside the home also joined and became relevant members of the English antislavery cause. One of these women was Martha Gurney, who, for Timothy Whelan, played the most prominent role “in raising the consciousness of the English people against the slave trade” between 1788 and 1796, in her role as an active printer and seller, as well as composer, of abolitionist pamphlets (46). Another was Anna Laetitia Barbauld, whose “Epistle to William Wilberforce, Esq. On the Rejection of the Bill for Abolishing the Slave Trade,” published in June 1791, appeared as an indignant response to the defeat of the motion presented two months earlier by William Wilberforce in the British Parliament to abolish the slave trade. A year later a sugar boycott was organized against the importation of sugar from the plantations of the West Indies, where women played an outstanding role. As Charlotte Sussman observes in “Women and the Politics of Sugar, 1792,” new conceptions of womanhood explain the appearance in abolitionist pamphlets of images of an energetic “female virtue conjoined to a kind of national sensibility” that transforms “the compassion of British women” into a symbol of “a specific national identity, a quality that distinguishes England from the rest of the world” (60). These British “antisacharist” rejections would be imitated by American abolitionists in the early decades of the nineteenth century, and used as a non-violent method to protest against the products derived from slave labor.

At the same time, during these last decades of the eighteenth century, literature for the little ones was conceived as the ideal space to instill justice and more humane attitudes towards Africans, as well as a treasured path to recruit future members in the ongoing struggle against slavery. A new understanding of children’s minds and their malleability, as well as their openness and receptivity to the fair treatment of creatures, increased the perception of printed material as the way to conversion. Thus, it did not take long for abolitionist publishers to jump on the bandwagon and devote their efforts to antislavery books for children. One of the most notorious was William Darton, a Quaker and prominent abolitionist and founder of the firm Darton and Harvey in 1787.

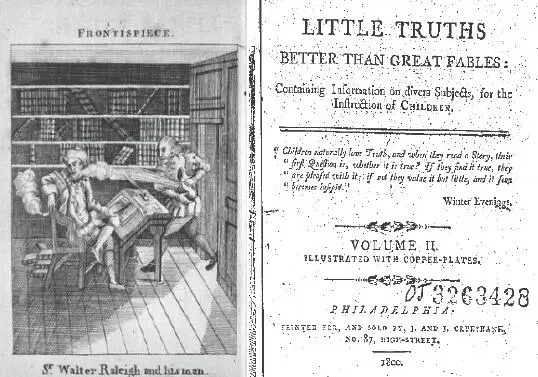

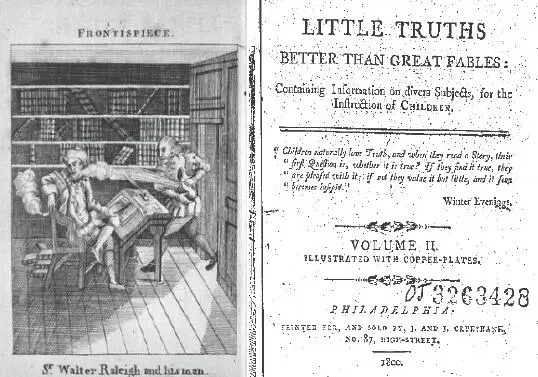

One of his earliest titles was Little Truths Better than Great Fables: In Variety [sic] of Instruction for Children from Four to Eight Years Old . Similarly to many other children’s books of the period, this volume appears as a list of questions asked by the children to their tutor. The topics range from animals and their habitats to the existence of races in the world, as well as to the injustice of the slave trade. In 1788 Darton published a second volume, Little Truths Better than Great Fables: Containing Information on Divers Subjects, for the Instruction of Children (Philadelphia, 1800). In this second volume he included subversive versions of what the Middle Passage was for the enslaved Africans—human cargo (14-18):

Why do they call some black peoples Negroes? From Negroland, the name of a large track of country, on the borders of the river Niger, in Africa. But why are they called slaves? On account of their being made so by great numbers of people who go from England, Holland, and France, to several parts on the coast of Africa, and encourage the strong and wicked people of the land to make war and heal away the inland natives, whom the Europeans purchase by hundreds, and carry to America and the West India islands, where these poor creatures must work so long as they live! and not contented with enslaving the parents, they retain their children’s children in perpetual slavery. Great numbers of those poor people have no other provisions allowed them in many places but what they raise for themselves, and that on the very day of the week set apart for a Sabbath! Great are the hardships they endure on board many of the ships: I have read, that six hundred and eighty men, women, and children were stowed in one ship! which was also loaded with elephants’ teeth. “It was a pitiful sight,” says the writer, “to behold how those people were stowed. The men were standing in the hold, fastened one to another with stakes, for fear they should rise and kill the whites; the women were between decks, and the children were in the steerage pressed together like herrings in a barrel, which caused an intolerable heat and stench.” And in this situation several of the poor creatures frequently die; others attempt to break their confinement, try to swim back again, and are often drowned. I did not think there had been any people in England so wicked as to do those things , I am sorry to say there are. And, why do they do them? From an evil desire of gain; that kind of love for money, “which is the root of all evil.”—To hear the groans of dying men,—the cries of many widows and fatherless children,—the bitter lamentations of a husband when torn from the arms of his beloved wife,—and the mournful cries of a mother and her children, when violently separated, perhaps, never to see each other again—I say, one would think, that those things might so affect the human mind, as to cause such practices to cease.

Читать дальше