He is also extremely humble and generous. I met Saunders once at a reading in Dallas, Texas, the state where he was born. While signing copies of Tenth of December for my wife and me, he asked if we were also writers. We replied in the affirmative, and while I am not certain what expression my wife was wearing, I could not help but think that I must have looked like a star-struck schoolboy. Of all the book signings I have attended, there are few in which I walked away feeling confident about the impression I made. Whether he remembers the encounter or not, I felt content walking away from Saunders because he made me feel like he cared. He said that he was sure we would meet again; the writing world is small. I felt like I mattered, not just as a writer but as a person. I imagine he makes a lot of people feel this way.

Since then, I have exchanged emails with him. Not only was I not ignored but he responded thoroughly. One of the characteristics of his writing that has particularly caught my attention is the integrity and candor of his choices—in terms of language, diction, detail, and subject. The simplicity of his writing style, both in his fiction and nonfiction, comes across as sincere especially because, upon reflection and analysis, the stories present complex scenarios. While some first-time readers may find his stories strange, this is not because what he presents us is far-fetched or unrelatable but because of his stylistic choices, which also make him a fresh and distinctive voice in literature. However, Saunders would be the first to insist that his approach to stories is practical. Here is part of Saunders’s response to a query about ethics in his literature:

I do, yes, think of stories as ethical objects—but I should first say that my way of thinking about stories is very...functional. I feel that my first goal is to make them compelling in some way for the reader—otherwise, nothing happens ethically or aesthetically or politically, because the reader doesn't go on, or does so tepidly. So a story, in my view, should be “ethical” in that I want some sense of outrage or sympathy to rise up in the reader so that she will continue to be interested . (HQ, ellipsis and italics original)

It may seem that Saunders, by his own words, aims primarily to entertain. However, if this is so then why the laurels? What makes his writing different? In this epoch of immersive digital entertainment, why bother to read the fiction of an author like Saunders? Each of his stories is a world in itself, one that exists just far enough from our own that we want to explore its terrain and just close enough to our own to leave us feeling something about life in our immediate world.

Reviews of his stories often focus on the blend of high and low art, the use of jargon and idiomatic speech, and his portrayals of working class America. Occasionally, his style is described as magical realism, but many of his stories could be considered speculative fiction. However, he is not exclusive to any one genre. What is common to his fiction is, as Adam Begley notes in his review of Pastoralia for The Guardian , “an unsettling amalgam of degraded language and high art: slogans, jargon and the crippling incoherence of daily speech, arranged on the page with meticulous care,” including the “brutal solecisms of the American vernacular,” which are played both for laughs and the “odd shot of beauty, too” (2000, n.p.). In his earlier fiction, the characters are usually working class American citizens. However, in the fiction he began publishing in the twenty-first century, the characters became more varied, including an increasing number of children, nonhuman animals, and even abstract shapes or objects. Saunders’s stories also tend to involve what Kasia Boddy, in The American Short Story since 1950 , describes as exaggerations “to the point of dystopia some familiar aspect of our late capitalist world before introducing a character who voices, either sincerely or in horror, an alternative vision of enlightened (or at least ‘light-craving’) individuality" (2010, 143-144). Many of his characters are striving to do the “right” thing without always knowing for certain what that is.

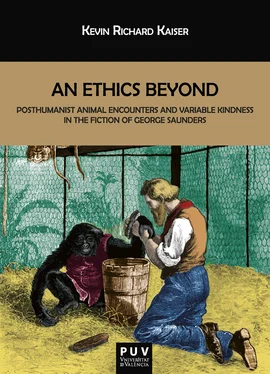

Drawing on the work of critics such as Layne Neeper, Julian Nalerio, David P. Rando, Todd Cesaratto, Sarah Pogell, Catherine Garnett, Christine Bieber Lake, and of those found in the first collection of criticism, George Saunders: Critical Essays (2017), edited by Philip Coleman and Steve Gronert Ellerhoff, a book newly published after I began work on this monograph, the following chapters acknowledge what these critics have discovered in the fiction of Saunders while exploring more rigorously some features of fiction that have not yet received much attention. Most of the essays have focused on issues of class, work, postmodernism, or language and style, especially as these topics pertain to contemporary American culture. A couple of essays take on ghosts or zombies, which appear in a few Saunders stories and especially in his novel. Surprisingly, few essays are devoted to satire or ethics, despite constant references by critics to Saunders’s satirical voice and ethical or moral edge. Finally, only one essay, by David Huebert, begins to explore notions of animality, despite the preponderance of nonhuman animals in Saunders’s fiction. None examines the fiction from the particular posthumanist angle that I take up, which is interested in the relations between human and nonhuman animals, nor how Saunders’s notions of ethics relate to those of philosopher Jacques Derrida and many posthumanist theorists.

My intent here is to demonstrate how Saunders’s writing, in particular his short fiction, can help us in several ways. First, it can assist us in identifying the posthuman world in which we reside and in maintaining awareness of the ethical challenges we may encounter. Next, it can provide us with a greater understanding of how this world and its ethical challenges function in posthumanist ways. Furthermore, it may allow us to theorize from a different standpoint. His writing might seem simple and, therefore, more accessible, but it is in no way vapid and is at once as comprehensible and relatable as it is disorienting. Thus, Saunders’s fiction, through an idiosyncratic language (characterized by an unorthodox use of capitals and a truncated syntax, among further rhetorical devices) and the presentation of complex ethical situations, allows us to examine concepts in the form of scenarios that may remain occluded to “straightforward” philosophical theorization. Such concepts give to his fiction, which often converges with “dark” satire, an ethical register that is synonymous with posthumanist ethics, making him an important commentator on contemporary American culture, while also marking his writing as an important resource in posthumanist discourse.

Saunders’s published fiction is comprised of four collections of short stories, a children’s book, a novella, a Kindle single, and a novel, along with two uncollected stories from the story-cycle Four Institutional Monologues (2000), 1“A Two-Minute Note to the Future” (2014)—published on fast-food chain Chipotle Mexican Grill bags 2—and the The New Yorke r story, “Mothers’ Day” (2016). Additionally, one early story, “A Lack of Order in the Floating Object Room” (1986) remains extant. Along with the fiction, he has also published a collection of essays, The Braindead Megaphone (2007), and an earlier chapbook, A bee stung me, so I killed all the fish (notes from the Homeland 2003–2006) , from which some of the essays published in The Braindead Megaphone first appeared. A number of these essays—for example, “Ask the Optimist!” and “Woof!: A Plea of Sorts”—read more like fiction. A few of his essays, such as The New Yorker exclusive, “Who Are All These Trump Supporters?” (2016), remain uncollected. Additionally, a commencement speech, delivered at Syracuse University, is published as Congratulations by the way: Some Thoughts on Kindness (2014). For my purposes here, I focus on the analysis of Saunders’s fiction, using his nonfiction to inform my commentaries where necessary, as I progress through the fiction chronologically.

Читать дальше