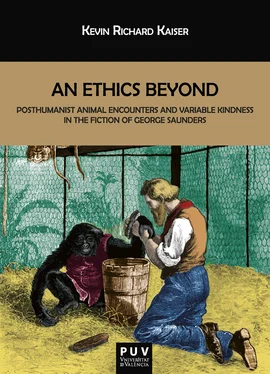

The sardonic sarcasm of his fiction allows him to “get away with” sentimentalism. Emotion becomes a relief from irony. The characters in his fiction work toward redemption in the more archaic sense of buying back freedom—freedom from the sociocultural constraints that impinge upon their sense of ethicality, their desire for what Saunders has called “radical kindness” (2007, “Medium Matters”), and what I call, borrowing from his commencement speech, “variable kindness.” 10

In the commencement speech, published as Congratulations, by the way: Some Thoughts on Kindness , Saunders describes the same ethical attitude present in his fiction. For him, because “kindness is variable , we might also reasonably conclude that it is improvable ” (n.p., italics original). 11Saunders’s sense of ethics is parallel to that proposed by many posthuman writers, including Jacques Derrida, who suggests a hyperethic: ethics beyond ethics. Saunders states a similar idea in a more straightforward manner, describing kindness as an ethics “that expands to include…well, everything” (CBW n.p., ellipsis original). In a 2017 article for The Guardian , he asserts that, in terms of his fiction, he achieves a sense of ethicality by attuning himself to his readers, clarifying that we often believe that

the empathetic function in fiction is accomplished via the writer’s relation to his [or her] characters, but it’s also accomplished via the writer’s relation to his [or her] reader. You make a rarefied place (rarefied in language, in form; perfected in many inarticulable beauties—the way two scenes abut; a certain formal device that self-escalates; the perfect place at which a chapter cuts off); and then welcome the reader in. (WWRD, n.p.)

The point is not to underestimate the reader and to develop a relationship with the reader.

In several interviews, Saunders further explains the relationship between kindness or compassion and his literature. For example, in the aforementioned 2007 The Colbert Report episode, Saunders explains in his first appearance on the show that when prose is “done right” it functions “kind of like empathy training wheels.” Kindness and compassion would become regular points addressed in his three subsequent interviews with Stephen Colbert. Much later, in an interview for the literary website Goodreads, Saunders replies to a query regarding compassion and the subject of his essay for The New Yorker , “Who Are All These Trump Supporters?”. I quote here and in the following paragraph almost the full response because it offers a first-person explanation of Saunders’s ethical awareness:

Depending on how you define compassion, actions are never beyond compassion. Sometimes we misunderstand [compassion] as being this bland, kowtowing niceness: Somebody hits you in the head with a rock and you say, "Thank you so much for the geology lesson." But compassion in Eastern traditions is much more fierce. It's basically calling someone on their bullshit. At the heart of it there's a clarity that would say, If I could press a button and make that person see his own actions, that would be the best. ( Goodreads n.p., brackets original,)

By mentioning “Eastern traditions,” Saunders may be alluding to his own Buddhist practice, which resonates with the kind of radical or variable kindness he elsewhere mentions.

Saunders continues by informing us of his own practice that safeguards him from indulging in negative emotions. As he describes it,

I'm just trying to be really watchful in my own heart for any kind of gratuitous negative emotion. I'm [thinking] Jesus was here, Buddha was here, Gandhi was here, Tolstoy was here, Mother Teresa was here, and they all said basically the same thing: Our capacity for understanding the other is greater than we think . It's not easy and we're not very good at it habitually, but we can get better at it and it's always beneficial. It's beneficial to you, and it's beneficial to the other. That's what I say—in real life I'm swearing under my breath on the internet. ( Goodreads n.p., brackets original, italics my own)

Here, Saunders references not only historical religious and philosophical figures but Tolstoy, whom we associate primarily with writing but who also later devoted himself to religion. Saunders also claims a premise aligned with posthumanist ethics: “Our capacity for understanding the other is greater than we think.”

This idea is consistent with Derrida’s notion of ethics beyond ethics, which has snaked its way into posthumanist ethics. Saunders does not claim that we can understand the Other, but that we have the capacity to do so. Despite the apparent simplicity of his language, his concept of ethics is careful not to assume that we can wholly understand the Other. Furthermore, critics of postcolonialism insist that we cannot speak wholly for the Other. This does not mean we should not try to understand the Other or, I argue, that we should refuse to try to speak on behalf of the Other but that to do so is difficult, as Saunders duly notes, and, moreover, dangerous. Indeed, thinking we can understand or speak for the Other can turn against us. I will discuss this in greater detail in the following chapter, but we should know that we must be careful never to assume we do know or speak entirely for the Other. Nevertheless, I concur with Saunders’s belief: we have a greater capacity to understand the Other than we generally acknowledge. In short, our power to empathize is greater than we think.

Writing in the 21 stcentury, both Wallace and Saunders seem to become increasingly more ethically aware; that is, their writing becomes even more emotionally engaged. Wallace’s essay on the Maine Lobster Festival, “Consider the Lobster,” 12originally published in Gourmet (2004) and later included in Consider the Lobster and Other Essays (2005), is a case in point. That his focus is on the pain of a nonhuman being is key. Wallace reports on the suffering of lobsters boiled alive for human gluttony and considers that

the questions of whether and how different kinds of animals feel pain, and of whether and why it might be justifiable to inflict pain on them in order to eat them, turn out to be extremely complex and difficult. And comparative neuroanatomy is only part of the problem. Since pain is a totally subjective mental experience, we do not have direct access to anyone or anything’s pain but our own; and even just the principles by which we can infer that other human beings experience pain and have a legitimate interest in not feeling pain involve hard-core philosophy—metaphysics, epistemology, value theory, ethics. (CL 246)

For Wallace, the greatest consideration “is that the whole animal-cruelty-and-eating issue is not just complex, it’s also uncomfortable” (CL 246). This uncomfortableness presents a range of moral questions, which Wallace leaves open to the reader to consider.

In “David Foster Wallace and the Ethical Challenge of Posthumanism,” Wilson Kaiser claims that “Wallace uses his own writing to foreground an ethical challenge that does not sit easily within the parameters of postmodernism” (2014, 153). Kaiser’s ruminations on Wallace’s fiction and essays may also be applied to Saunders’s writings. Kaiser argues that “Wallace’s literary worlds, for all their commitment to an ethics, do not assume personal autonomy or an irresoluble answerability to an Other” but “rather are “situated in a concrete engagement with a specific milieu that contains a multiplicity of human and non-human actors” (Kaiser 154). According to Kaiser, the ethics found in Wallace’s “literary worlds” are posthuman rather than postmodern. They avoid postulating generalizing claims, focusing instead on “affinities within a network of possibilities” (Kaiser 155); they rarely moralize. The same is true of Saunders’s writing.

Читать дальше