Quebec, therefore, has had an impact on both LPP practice and LPP research. As a result, the province and its legal framework provides an interesting benchmark against which to compare other polities’ policy approaches. An early study to do so is Thomas (1977), in which language movements (at that time in their formative stages) and nationalisms in Wales, Ireland, and Quebec are compared. Others, such as Backhaus (2009), have focussed on the legislation of the linguistic landscape (i.e., visible language in public space), and compared, in Backhaus’ case, Quebec with Tōkyō. In the present study, the policies in Quebec are compared with those found in Wales and in Singapore. The reasons for this choice of polities, explained in more detail in section 6.1, are found in the presence, in all three, of a population of native speakers of English of varying proportions, in the presence of languages that government policy-makers deem worthy of promotion, and, more generally, in the existence of a sophisticated LPP framework in all three polities, operating, of course, at different levels within each society, and enforced and policed with varying degrees of force. All three policy frameworks are couched within larger national discourses, whose obvious differences gloss over underlying similarities. These will, in due time, be made explicit in chapter 7.

1.2 French and English in Quebec

Before embarking on the present study, it is useful to provide some background information on the varieties of French and English spoken in the province of Quebec. Both colonial languages have been continually present in the area of present-day Quebec since the sixteenth century. The distance between the settlements in the new world and the metropolitan centres in Europe being such that contact was limited by the long transatlantic voyage, independent linguistic developments took place in North America that did not happen in Europe; likewise, some changes in European French and ‘European’ (British) English did not cross the ocean. In what follows, a brief description of the varieties of French and English in the province is given.

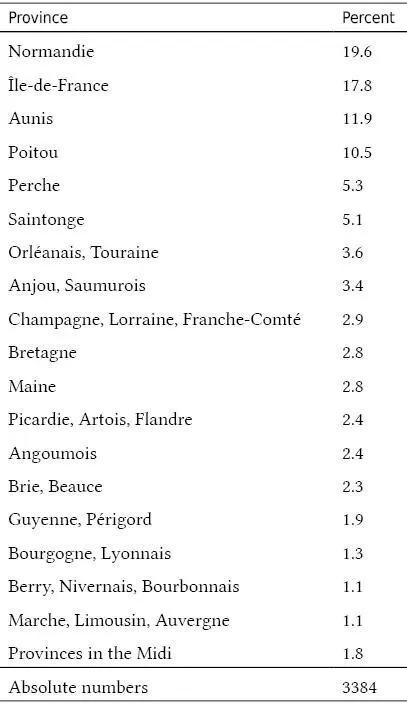

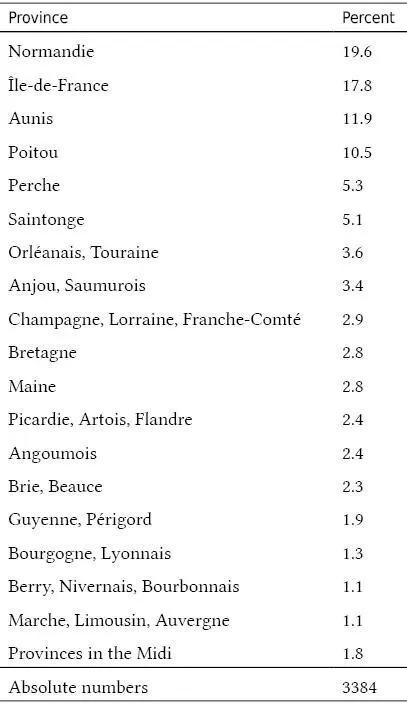

There is no shortage of research into the variety of French known as (français) québécois . Many focus on the lexicon (Dulong, 1989; Poirier, 1998), the grammar (Léard, 1995), and the phonology (Walker, 1984; Dumas, 1987; Ostiguy and Tousignant, 2008), others take a more historical linguistic approach (Charbonneau and Guillemette, 1994; Gendron, 2007). The French presence in North America can be traced back to the mid-sixteenth century, with more permanent settlements stabilising in the early seventeenth century (see section 2.1 for a detailed historical background). The language brought across the Atlantic by these settlers was the vernacular spoken by former residents of a rather restricted set of provinces in metropolitan France. The vast majority hailed from west of Paris and north of Bordeaux; the provinces of the South, i.e. those of the langue d’oc , played a negligible part in the settlement history. Charbonneau and Guillemette (1994) provide a breakdown of the numbers from their study, given in Table 1.1, which shows that over a third of settlers came from Normandie and Île-de-France combined, another fifth comes from the Aunis-Poitou area (around La Rochelle and Poitiers); on the other hand, langue d’oc provinces account for just 4.8 %. An overview of the provinces of origin is given in Figure 1.1

Table 1.1: Province of origin of early French settlers (Charbonneau and Guillemette, 1994, 169).

The data behind these numbers come from marriage records, which are the prime source of such information in the Quebec context. Charbonneau and Guillemette (1994) go to great lengths to explain the care that should be taken when analysing such historical data. For one, manuscript records are hard to read. Secondly, the declaration of origin, normally made by the settlers themselves, may not be entirely accurate, and sometimes differs in terms of precision: sometimes the city is mentioned, sometimes only the province, a bishopric, a parish, or just a geographical term such as an island. Actually pinpointing these toponyms to a precise cartographic location is also not as straightforward as it may seem. Provinces under the Ancien Régime did not necessarily have clearly-defined boundaries, at least not from an administrative point of view (Charbonneau and Guillemette, 1994, 163).

Two competing views on the emergence of the rather uniform Colloquial Quebec French (CQF) exist, depending on whether dialect levelling ( le choc des patois ) happened in France or in New France. The latter of these views is taken by Barbaud (1984), Barbaud (1996), who argues that immigrants spoke, before their arrival in New France, their provincial patois in France. Except for those from the Île-de-France region, therefore, the majority of settlers were non-francophone. The prime linguistic integrating factor is considered to include the 900 filles du roy , young women educated (typically in Paris itself) in the French language of the court, specially selected for the task of relocating to New France between 1665 and 1673 to help the primarily male settlers populate the colony. Barbaud hypothesises that they eventually became the mothers of an entire generation, whose linguistic unification they shaped through their common language background, rather than through any other top-down language policy.

Figure 1.1: Historic French provinces (Charbonneau and Guillemette, 1994, 164).

By contrast, Wittmann (1995), Wittmann (1998) argues for a koinéisation in France, prior to emigration. His comparative structural analysis of several colonial and metropolitan varieties of French reveals a three-fold classification of varieties of seventeenth-century French: a first group comprises ‘northern’ French varieties, including rural Parisian and the language of the court. A second type is the urban koiné that emerged in Paris and that would form the basis for subsequent linguistic integration in other metropolitan French cities. A final group comprises creole varieties. Wittman’s contention is that would-be colonisers would usually spend a considerable amount of time in urban settings prior to emigration, thereby acquiring the koiné that would act as a supra-regional levelled variety. If all or the majority of settlers indeed came from such urban agglomerations, the linguistic distance between settler groups would have been much reduced before the crossing of the Atlantic. Therefore, colloquial speech in New France would have been much more homogeneous than that of metropolitan France, where much diversity (to the point of mutual unintelligibility) prevailed until well after the Revolution.

The evolution of spoken CQF since the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries took a path different from the one the French language took in Europe, partly because of the geographical distance and partly because of the political isolation after the British conquest of 1760. Present-day CQF is markedly different from European French. It differs, obviously, at the lexical level, with many English loans ( wiper , fun , cute , checker ‘to verify’, au meilleur de ma connaissance ‘to the best of my knowledge’), archaisms ( barrer (une porte) ‘to lock (a door)’, souliers ‘generic footwear’, noirceur ‘darkness’, maganer ‘to damage’), and a distinct repertoire of swearwords – unknown elsewhere – directly derived from Catholic liturgical items ( crisse ‘Christ’, câlisse ‘chalice’, tabarnak (from tabernacle ‘church tabernacle’)). The phonology shows a consonant system that is identical to that of European French, but with the additional rule that the dental plosives /t/ and /d/, when before the high front vowels and semi-vowels /i/, /y/, /j/, and /ɥ/, affricate to become /t͜s/ and /d͜z/ respectively; in addition, certain final consonant clusters may be reduced. Vowel phonemes are more numerous in CQF, with the maintenance of distinctions between pairs of vowels that have been lost in Europe: this includes the pairs /a/ and /ɑː/ ( patte vs pâte ), /ɛ/ and /ɛː/ ( mettre vs maître ), /ø/ and /ə/ ( jeu vs je ), and /ɛ̃/ and /œ̃/ ( brin vs brun ). In the basilect, /œ̃/is rhotacised to [œ̃˞] , and /ɛː/, /o/, and /ø/ may nasalise before nasal consonants. /ɑ̃/ may be pronounced as [æ̃] in open syllables and as [ãʊ̯̃] in checked syllables. In final open syllables, /a/ is, in basilectal speech, rounded to [ɔ]. In words with the spelling ⟨oi⟩, remnants of the older pronunciation may occur in realisations such as [wɔ], [wɛ], or even [ɛ].

Читать дальше