A glimpse into the linguistic realities of late eighteenth-century Quebec can be caught, for instance, in a collection of Montreal Gazette advertisements seeking help in retrieving fugitive slaves, published in Extian-Babiuk (2006) (see also Mackey 2010b). Consider the excerpt below, taken from an advert posted on 21 July 1791 by one J. Joseph of Berthier (present-day Berthierville, on the north shore of the Saint Lawrence River, halfway between Montreal and Trois-Rivières):

RUN AWAY From the subscriber in the Night of the 13th instant: A NEGRO WENCH, named Cloe, about thirty years old, pretty stout made, but not tall; speaks English and French , the latter not fluently. […] She is supposed to have gone off in a canoe with a man of low stature and dark complexion, who speaks English, Dutch, and French . (Mackey, 2010b, 334, emphasis mine)

Many of the adverts listed in Extian-Babiuk (2006) and Mackey (2010b) mention the languages used by the slaves, many of whom used several languages (viz. ‘speaks English and French fluently’ (Extian-Babiuk, 2006, 39), ‘parle Anglois et François’ (Mackey, 2010b, 335), ‘speaks good English and some broken French and Micmac’ (Mackey, 2010b, 337), or, in the ‘for sale’ section, ‘She can adapt herself equally to an English, French or German family, she speaks all three languages’ (Kesterton, 1967, 7)). The highlighting of language proficiency serves primarily as part of the general description of the fugitive. Knowledge of English or French must have been, at least to a certain extent, a function of the ‘master’ household’s language(s). Nevertheless, the evident multilingualism present in at least some of these peripheral (i.e. powerless) members of early British North American society is an indication of the wider contact pattern between languages: slaves may have changed hands from anglophone to francophone households, suggesting proximity and commercial exchange between the two communities. Bilingualism in the slave population may also have come as an advantage to their ‘owners’, who could thus rely on the language skills of their workforce. It is also worth noting that this disenfranchised part of the population was absorbed (though not fully assimilated) into the general Canadian population after the Slavery Abolition Act 1833 (Drescher, 2008). Their language repertoires, therefore, are of relevance to the history of language contact in Quebec and Canada.

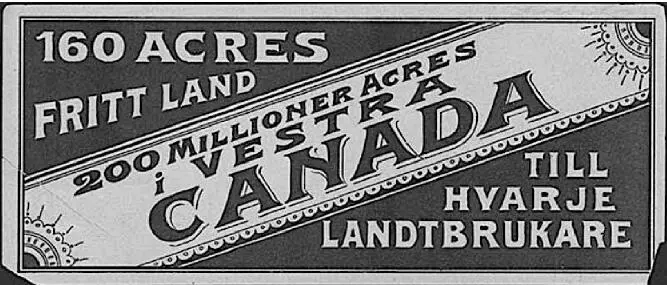

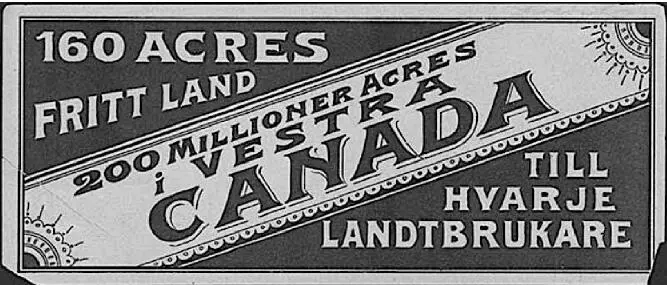

The various waves of immigration moving into British North America also offer an insight into the languages used by early Canadians. While immigration from France was reduced to a trickle after the Conquest, large-scale efforts to populate the rather empty Prairies were undertaken after 1867. These efforts also took the form of organised advertisement campaigns in locations of interest, with immigrants coming ‘preferably from Great Britain, the United States, and northern Europe, in that order’ (Knowles, 2007). Posters were printed for dissemination there, often in the language of the target population. Figure 2.2 shows such an advert in Swedish, promising ‘160 acres [i.e. 65 ha] of free land for every farmer’ out of the 200 million available in Western Canada.

To sum up the political situation, the Conquest of 1760 and the Treaty of Paris of 1763 handed over New France to Britain, and ‘Quebec’ was organised as a British province (also comprising present-day eastern and southern Ontario) in the same year. In 1774, the Quebec Act granted French civil law, as well as religious and linguistic rights (detailed below) to the inhabitants of Quebec. The term ‘British North America’ was used after 1783 to refer to territories under British control north of the newly independent United States of America. The Constitutional Act 1791 divided Quebec into two provinces, Upper Canada (roughly equivalent to present-day southern Ontario, extending as far north to the watershed of the Hudson Bay) and Lower Canada (now southern Quebec and Labrador), named for their respective locations on the Saint Lawrence River. Unification of the two provinces as the ‘United Province of Canada’ took place in 1841, but ‘Confederation’, a process started with an increase in local autonomy in the British North American provinces in the 1840s, eventually culminated in the British North America Act 1867. The BNA Act brought together the provinces of Canada (i.e., Ontario and Quebec), Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick into a single political entity, a ‘dominion’, named Canada. Rupert’s Land, owned by the Hudson Bay Company and including the entire continent west and north of the Province of Canada (excluding British Columbia), was brought into the Confederation in 1870 as the Northwest Territories and Manitoba. A year later, British Columbia joined, extending the country’s reach from one ocean to the other.2

Figure 2.2: Poster advertising emigration to Canada in Swedish (from Gagnon, 2016). The orthography used places the poster before the spelling reform of 1906.

The colony of Prince Edward Island joined in 1873. Yukon was carved out from the Northwest Territories to become its own territory in 1898, as were Saskatchewan and Alberta in 1905 (as provinces rather than territories). Newfoundland and Labrador, which had remained a colony until it became a dominion in its own right in 1907, finally joined in 1949. Lastly, the territory of Nunavut was separated from the Northwest Territories in 1999, resulting in the largest area (1.8 million square kilometres) and the smallest population (31906 in 2011) of any province or territory. Subsequent to Confederation, Canada remained a dominion under British rule, with gradually increasing autonomy being transferred to Ottawa (named the capital of the Province of Canada in 1857), such as with the Statute of Westminster 1931, which gave legislative independence to dominions of the Empire. However, only after 1982 was it possible for constitutional matters to be debated and decided solely by Canada, without each amendment to the constitution having to be made by the British parliament. The Canada Act 1982, passed by the parliament of the United Kingdom, sealed the ‘patriation’ of the constitution, i.e. its full transfer under Canadian responsibility. For all intents and purposes, full sovereignty had been achieved: even though the sovereign head of state, the Queen of Canada, is the same person as the sovereign head of another fifteen Commonwealth Realms, the Crown (represented in Canada by a federal Governor General and by provincial Lieutenant Governors) remains a distinct legal entity in each realm.

2.2 Canada: an officially bilingual country

Under French colonial rule, French was obviously the de facto official language in New France. The Conquest of 1760 led to the Treaty of Paris in 1763, which formalised the transfer of sovereignty from France to Britain. Its effects were felt in large parts of the world where the two colonial powers were fighting for supremacy, also, therefore, in North America. The previously French subjects became British subjects, with obvious repercussions on the legal framework that moved from French civil law to British common law and on the religious order, with Catholicism (severely opposed by the British) now no longer state religion. The religious issue, in fact, proved to be a major concern: with British rule also came British laws, among them the requirement (dating to 1559), for senior civil and public servant, to take an oath of allegiance rejecting the Catholic faith. This was unacceptable to a large majority of Catholic French Canadians. In the larger colonial context of the brewing displeasure in the nearby thirteen American colonies (soon to erupt in full-blown revolution), the British were anxious to secure the support of the Quebec population; the provisions of the Quebec Act 1774 sought to do so. This act, in addition to extending the Province of Quebec beyond the Great Lakes (to be bounded by the rivers Mississippi and Ohio, i.e. the old borders of New France without Louisiana), removed references to religion from the oath of allegiance, and declared that subjects in the province ‘may have, hold, and enjoy, the free Exercise of the Religion of the Church of Rome’ (i.e., Catholicism, Quebec Act 1774, s V); the Catholic Church was also allowed to collect tithes again. Further, it restored the use of French civil law for private law, although British common law was maintained for public law.

Читать дальше