Becoming a Reflective Practitioner

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Becoming a Reflective Practitioner» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Becoming a Reflective Practitioner

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Becoming a Reflective Practitioner: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Becoming a Reflective Practitioner»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Becoming a Reflective Practitioner

Becoming a Reflective Practitioner

Becoming a Reflective Practitioner — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Becoming a Reflective Practitioner», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Many writers have written about the nature of care and the demand that puts on carers to act for what is espoused as the ‘good’. Consider Logstrup’s (1997, p. 18) ethical demand:

By our very attitude to one another we help to shape one another’s world. By our attitude to the other person we help to determine the scope and the hue of his or her world; we make it large and small, bright or drab, rich or dull, threatening or secure. We help to shape his or her world, not by theories and views but by our very attitude to him or her. Herein lies the unarticulated and one might say anonymous demand that we take care of the life which trust has placed into our hands.

Clearly attitude, as noted previously, is a significant aspect being person‐centred. Negative attitudes lead to such phenomena as the ‘difficult patient’, the ‘interfering relative’ and racism. For example, issues surrounding racism continue to surface (Blackford 2003; Puzan 2003), perhaps more so at this time of writing in light of the ‘Black lives matter’ movement 2 and the global response to George Floyd’s death by a policeman in the USA on 25 May 2020 demanding justice and equality. As Puzan (2003, p. 194) writes:

There is so much familiarity in talking about the alleged racial differences of non‐white people in public discourse and so little familiarity in talking about those racial properties attached to being white, that the concept of whiteness (or a recognition of racial formation) has little resonance within nursing (citing Jacobson 1998). While issues related to cultural difference are not ignored, they rarely include the difference specifically engendered by ‘whiteness’, which is structured to avoid and deflect interrogation or critical reflection .

Puzan’s words challenge all healthcare practitioners, health organisations, and health systems about the right attitude to hold towards all people irrespective of race to ensure cultural safety and health equity. A commonly used definition of cultural safety is that of Williams (1999, p. 213), who defines cultural safety as: an environment that is spiritually, socially, and emotionally safe, as well as physically safe for people; where there is no assault challenge or denial of their identity, of who they are and what they need. 3 From a healthcare perspective, Cultural safety is the effective nursing practice of a person or family from another culture that is determined by that person or family. Unsafe cultural practise is defined as an action that demeans the cultural identity of a particular person or family (Nursing Council of New Zealand 2002, p. 9). 4

Different Perspectives

Every experience involves a web of different people; patients, relatives, and diverse professionals set against an organisational background. Each person involved will have a perspective on the particular situation. These perspectives are often contradictory in that people may see the situation differently. Hence it is necessary for the practitioner to inquire into these different perspectives beyond her or his own partial view. Inquiry into other perspectives is termed empathic inquiry . It is the path to connect with the other and opens a gate to tune into the other’s wavelength and talk about issues. 5 Imagine the other’s perspective requires stepping back and taking an objective stance free from one’s own personal perspective. It is akin to putting yourself in the other person’s shoes to consider their view of the situation. Understanding the other’s perspectives gives a bigger picture of the situation and sets up the potential for resolving any ethical dilemma and conflict over what is the right way to respond.

Kant’s moral imperative asserts ‘do as you would be done for’. However, this runs the risk of imposing your own values into the situation. For example, viewing an elderly patient ‘as if that was my mother’. The problem with this principle is that the patient is not your mother and that imposing such a position may be misguided because of identification and emotional entanglement.

Ethical Mapping

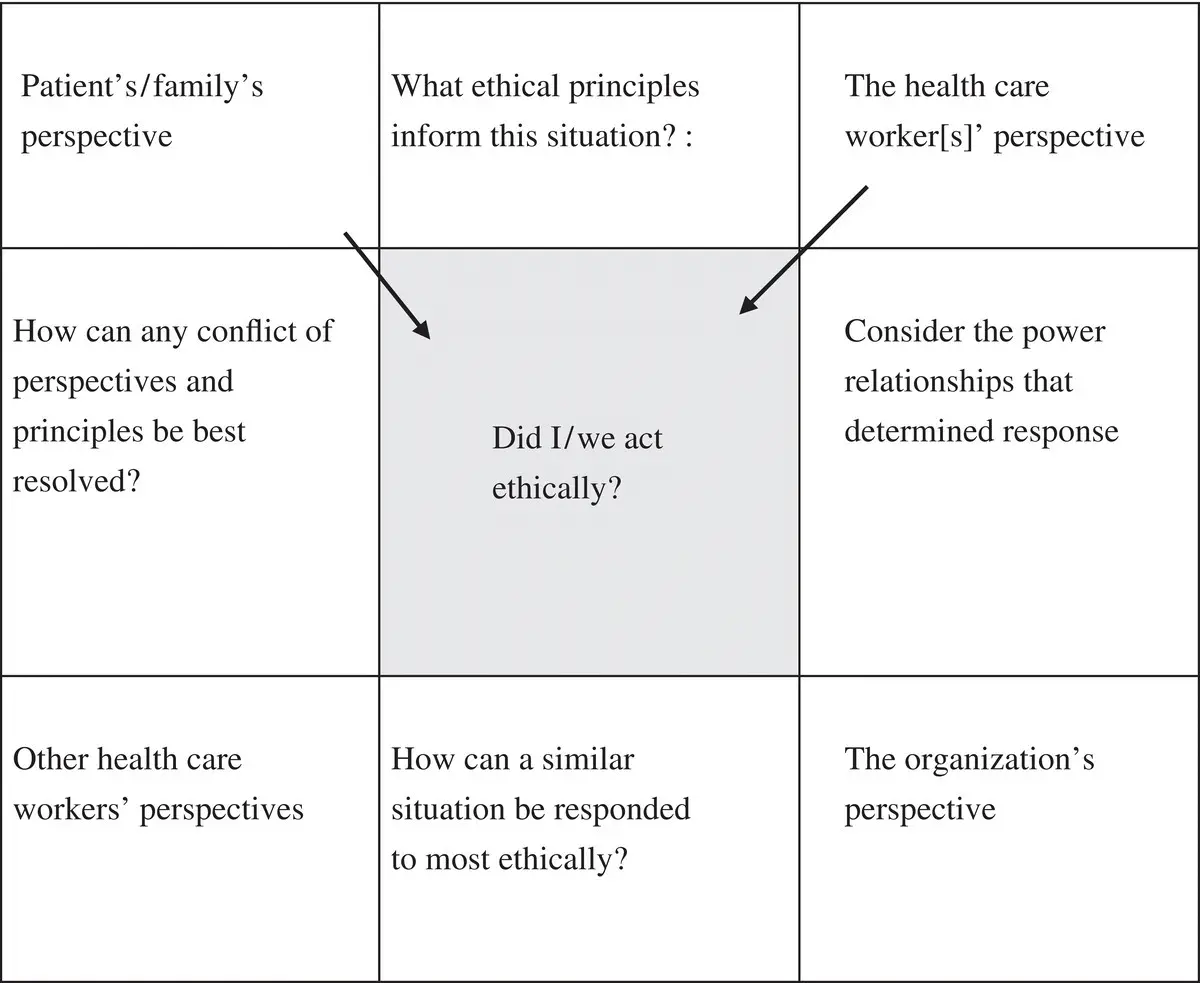

The perspectives of others can be mapped ( Figure 4.1). Then any conflict between perspectives can be viewed in the light of ethical principles and issues of authority with the intention of understanding the most ethical response to inform future situations. It shifts from an issue of personal responsibility to act for the best to a collective one.

Following the ethical map trail

1 Pose the question – did I/we act for the best,

2 Consider different perspectives commencing with the practitioner’s own perspective,

3 Consider which ethical principles apply in terms of the best decision,

4 Consider what conflict exists between perspectives/values and how these might be resolved, and

5 Consider authority relationships that determined action.

The last point acknowledges the significance of authority in making decisions, no matter the ethical perspective. In reality, decisions are not necessarily made in terms of what’s best for the patient or family, but in terms of professional interest and dominance that is implicit within normal patterns of relating between professionals 6 . Hence to act for the best, the practitioner may need to challenge the authority of others by championing the most ethical response – what I refer to as the Achilles heel of medical dominance.

Loxley (1997) identifies a number of questions that are useful to inform stages 5 and 6 of ethical mapping:

Who defines the problem?

Whose terms are used?

Who controls the domain or territory?

Who decides on what resources are needed and how they are allocated?

Who holds whom accountable?

Who prescribes the activity of others?

Who can influence policy makers?

FIGURE 4.1 Ethical mapping (adapted from Johns 1999).

Anticipatory Reflection

Given a similar situation, how could I respond more effectively, for the best and in tune with my vision?

The practitioner asks

‘What are my options for responding differently, more effectively, and in tune with my values, given a similar situation?’ Is my vision still adequate in light of this past experience?

What are the potential consequences of responding differently?

How do those influencing factors need to shift so I can respond differently?

The cue opens a creative space to play with possibility and plant seeds of possibility in the practitioner’s mind (Margolis 1993). It is an invitation to throw open the shutters of the mind to see things laterally, to get out of our normal frame of reference and challenge our habitual ways of perceiving and responding to practice. It is like opening different windows in the mind to see things from new perspectives.

O'Donohue (1997, pp. 163–164) writes: ‘Through these different windows, you can see new vistas of possibility, presence, and creativity. ‘Complacency, habit, and blindness often prevent you from feeling your life. So much depends on the frame of vision – the window through which we look’.

Get curious! Responding to this cue may be difficult when the practitioner is stuck in a groove of habitual practice or lacks imagination to see the situation differently. Here guides and peers are most helpful to engender alternatives.

In weighing up the best response given a similar situation, the practitioner considers the potential short and long term consequence of each option.

Am I Able to Respond as Envisaged?

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Becoming a Reflective Practitioner»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Becoming a Reflective Practitioner» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Becoming a Reflective Practitioner» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.