Joseph J. Torres - Life in the Open Ocean

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Joseph J. Torres - Life in the Open Ocean» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Life in the Open Ocean

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Life in the Open Ocean: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Life in the Open Ocean»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Life in the Open Ocean: The Biology of Pelagic Species

Life in the Open Ocean: The Biology of Pelagic Species

Life in the Open Ocean — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Life in the Open Ocean», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

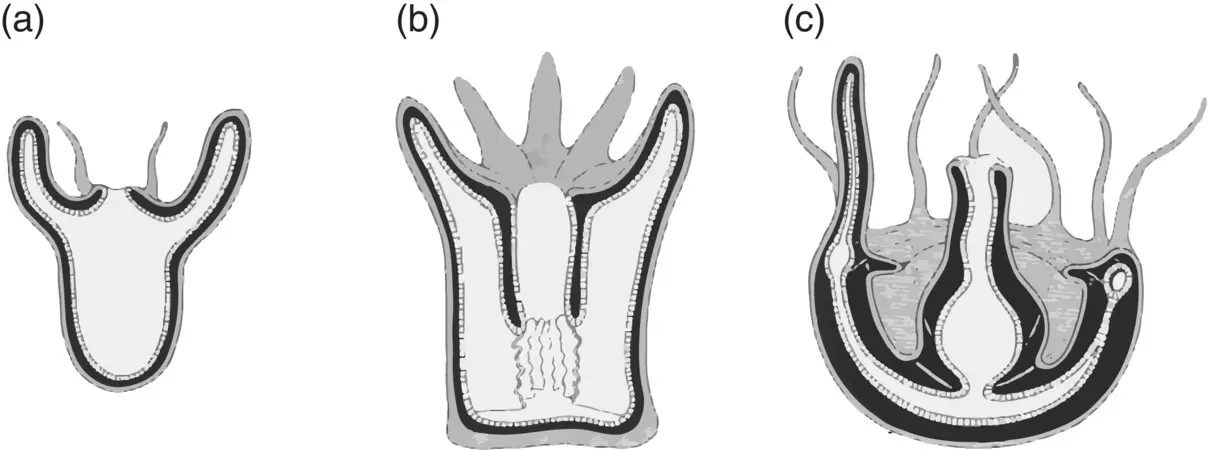

The Medusozoa include the taxa of main concern, the free‐swimming pelagic jellies. Five classes of Medusozoa have been identified, of which three, the Cubozoa (cubomedusae), Scyphozoa (the large jellyfishes), and the Hydrozoa (hydroids and hydromedusae), will garner the most attention in the following pages. Though anthozoans are major players in the benthos of all oceanic systems, our chief interest here is their structural relatedness to the free‐swimming jellies. The similarities between polyps and medusae are best visualized by turning a medusa upside down ( Figure 3.1). It is easy to see that both polyps and medusae may be characterized as having a central gut (a gastrovascular cavity or stomodeum) surrounded by a row of radially arranged tentacles.

Figure 3.1 Tissue layer homologies in cnidarians. (a) A hydrozoan polyp; (b) an anthozoan polyp; (c) a hydromedusan medusa, shown upside down for similar orientation. The outer tissue layer is ectodermal (epidermis); the inner tissue layer is entodermal (gastrodermis); the middle tissue layer is mesenchyme/mesoglea.

Phylum Cnidaria

Subphylum Medusozoa

Class Hydrozoa

Subclass HydroidolinaOrder Athecata (Anthomedusae or Anthoathecata)Suborder Capitata (Porpita, Millepora, Coryne)Suborder Aplanulata (Tubularia, Corymorpha)Suborder Filifera (Stylaster, Bouganvillia)Order Thecata (Leptomedusae or Leptothecata) (Aequorea, Campanularia)Order SiphonophoraSuborder – Cystonectae (Physalia)Suborder – Calycophorae (Muggiaea)Suborder – Physonectae (Agalma)

Subclass TrachylinaOrder LimnomedusaeOrder TrachymedusaeOrder Narcomedusae

Class Cubozoa– Sea wasps and box jellies

Order Chirodropida (Chyronex)

Order Carybdeida (Carybdea)

Class Scyphozoa– “true jellyfish”

Order – Coronatae – coronate medusae, common in deep‐sea – Periphylla

Order – Semaeostomae – most typical large jellyfish – e.g. Aurelia

Order – Rhizostomae – cannonball jellies

Class Staurozoa– Stalked jellyfish. Small sessile individuals – polypoid ( Halyclistis )

Class Polypoidozoa– Intracellular parasites of developing fish eggs. Monospecific.

Subphylum Anthozoa

Class Anthozoa

Subclass Octocorallia – three orders and six suborders, includes soft corals, gorgonians, sea pens, and sea pansies.

Subclass Hexacorallia – six orders, includes the true sea anemones, stony corals, black corals, and tube‐dwelling anemones.

Subphylum Myxozoa

Intracellular parasites of marine and freshwater vertebrate ectotherms, annelids, bryozoa, and sipunculids. Two classes and two orders. About 2200 species.

Open‐ocean species are often not as well understood or well described as nearshore species because of insufficient access to specimens. This is particularly true of the Cnidaria. Taxonomic keys and good drawings of species are limited, and many of the best treatments of cnidarian groups are quite old. For decades, the oceanographer’s gold standard for identifying medusae resided in the works of two authors, F. S. Russell ( Medusae of the British Isles , volumes I and II) and P. L. Kramp (“The Hydromedusae of the Atlantic Ocean and Adjacent Waters”; Medusae of the World). Both authors built on the work of luminaries preceding them, most notably A. G. Mayer’s three‐volume Medusae of the World . Recently, the benchmark works of Kramp and Russell have been supplemented with a new, multiauthor, treatment on the South Atlantic Zooplankton (Boltovskoy 1999) that gives a very nice summary of the systematics of the Cnidaria, though as in all things systematic it is not one that is universally accepted. Classification within the Cnidaria is very well treated by Mills et al. (2007) in the new Light and Smith’s Manual (J. T. Carleton, ed.).

The classification scheme above includes recent consensus views on major groups within the Cnidaria and how they are related. Two groups stand out as unusual within the hydromedusae: the siphonophores and the “by‐the‐wind‐sailors” (sometimes known as the chondrophores). We will treat them separately because their biology is different from the remainder of the hydromedusae, even though they are now considered to be an order (Siphonophorae) and a family (Porpitidae) within the hydromedusae.

If all the classification schemes are considered together, including those of Kramp and Russell, five basic divisions within the medusae of the hydromedusae are apparent: the Anthomedusae, the Leptomedusae, the Limnomedusae, the Trachymedusae, and the Narcomedusae. Species in the first three groups have a polyp stage in most instances and thus show alternation of generations. The second two groups show direct development. We will consider the medusae within the Hydromedusae to have the five basic divisions noted above, which most closely approximate the classical literature. Whether those divisions are orders or suborders is less important than the fact that the hydromedusae can be readily segregated morphologically using those divisions, and they have been for the better portion of 100 years.

The Hydromedusae

Morphology Basics

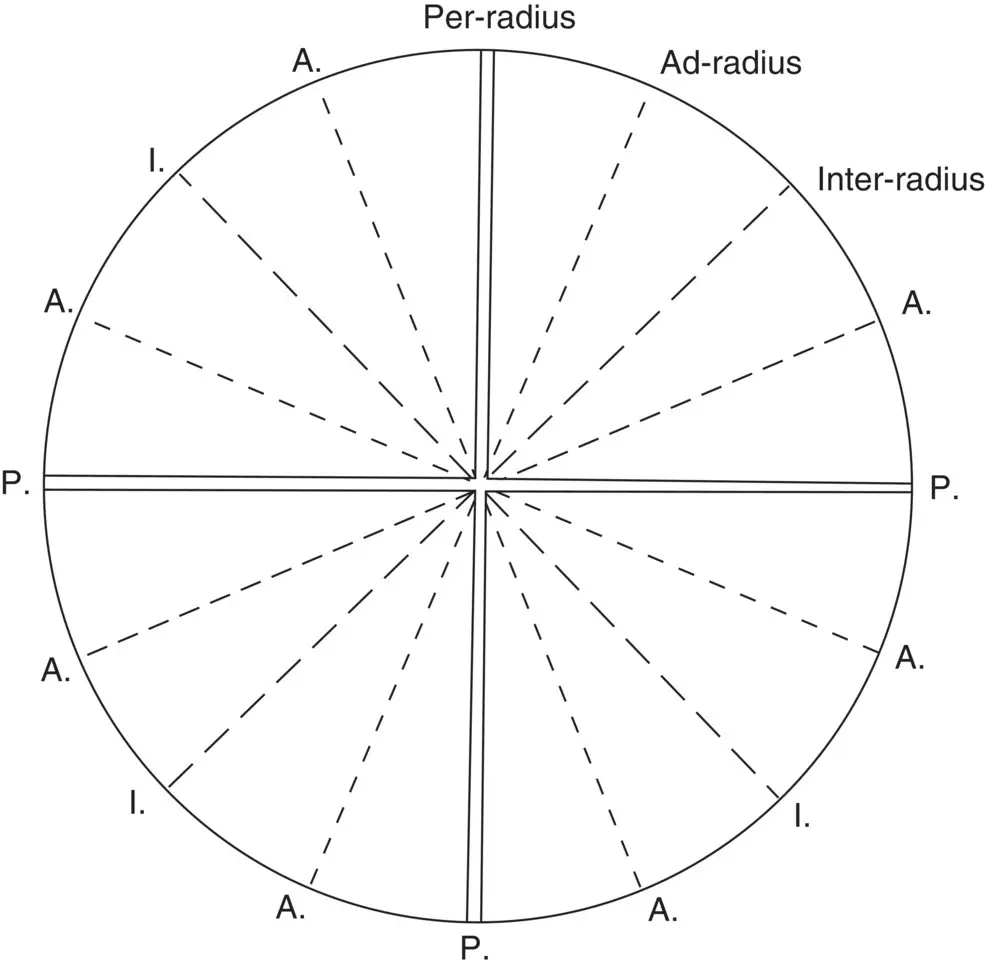

The Cnidarians are all radially symmetrical ( Figure 3.2); their parts are arranged around a central axis much like the spokes of a bicycle wheel are arranged around the hub. Each of the radii has names that are used in classification. The central axis or hub is the oral–aboral axis or gut. Between the “hub” and the “rim,” body parts are arranged concentrically ( Figures 3.3and 3.4). In perfect radial symmetry, a plane bisecting the animal in the axis of the hub will result in two perfectly equal halves, no matter where the plane is placed. Most often, and even in the hydromedusae, the morphology is modified to biradial (two equal halves) or tetramerous (four equal quarters) radial symmetry. The radial symmetry of medusae is important to their foraging strategy. Prey are equally accessible from all points of the compass, which, for an ambush predator, is a distinct advantage.

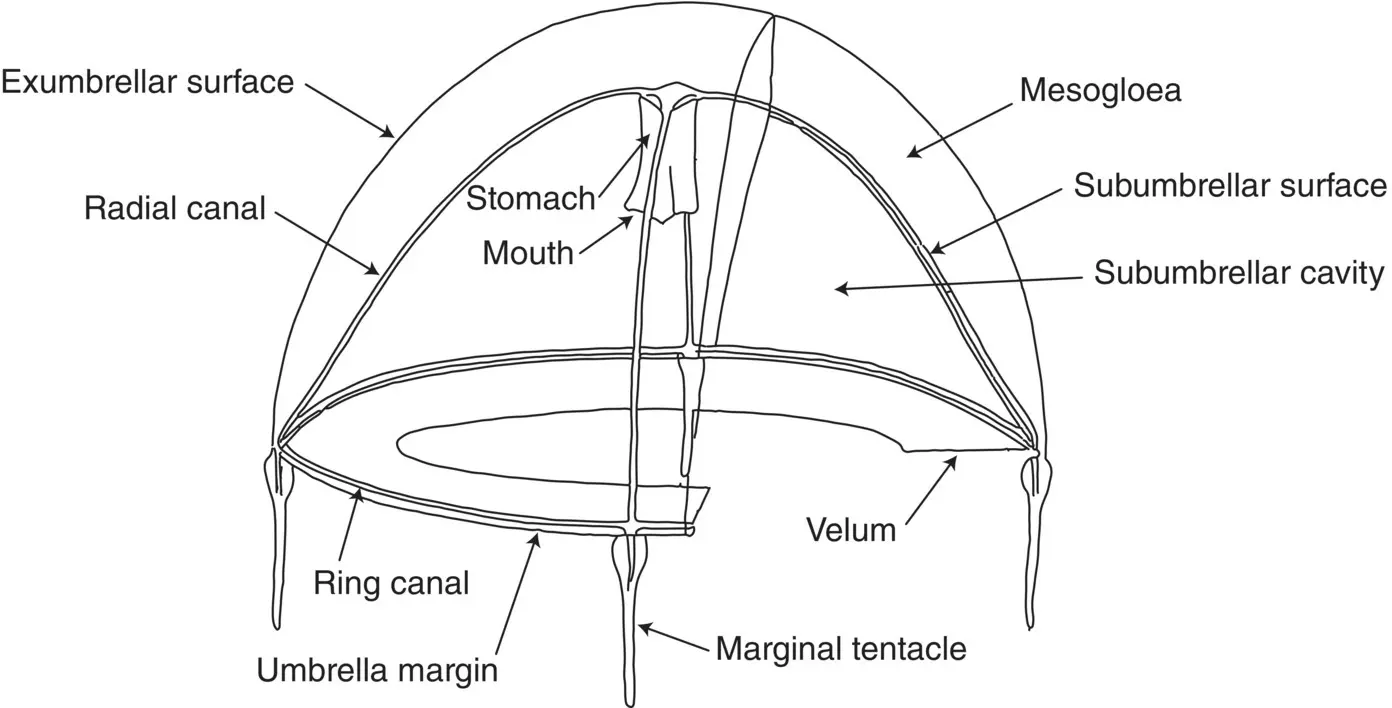

Figure 3.3shows the basic body form of a hydromedusa. The outer, or exumbrellar, surface and the inner, subumbrellar, surface are separated by a deformable gelatinous acellular mesoglea. The mesoglea acts as a primitive skeleton, giving a medusa its characteristic shape and providing a surface against which muscle tissue can act to propel the medusa through the water.

Figure 3.2 Diagram to define the radii of a medusa. P . are the per‐radii on which the four primary radial canals lie. I . are inter‐radii and A . are ad‐radii.

Source: Adapted from Russell (1954), figure 1 (p. 2).

Figure 3.3 Diagram of a medusa with one quadrant removed.

Source: Adapted from Russell (1954), figure 2 (p. 3).

Swimming bells range in shape from tall to spherical to highly flattened in appearance ( Figure 3.5a, Russell 1954). The stomach is a simple sack that projects downward from the subumbrellar surface and can vary considerably in length and morphology. The opening of the stomach or “lips” may vary from a simple circular opening to a highly crenulated and folded appearance. In some cases, the mouth is surrounded by small oral tentacles ( Figure 3.5b).

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Life in the Open Ocean»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Life in the Open Ocean» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Life in the Open Ocean» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.