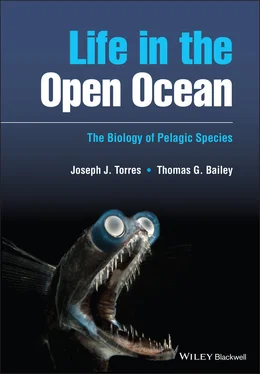

Joseph J. Torres - Life in the Open Ocean

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Joseph J. Torres - Life in the Open Ocean» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Life in the Open Ocean

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Life in the Open Ocean: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Life in the Open Ocean»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Life in the Open Ocean: The Biology of Pelagic Species

Life in the Open Ocean: The Biology of Pelagic Species

Life in the Open Ocean — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Life in the Open Ocean», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

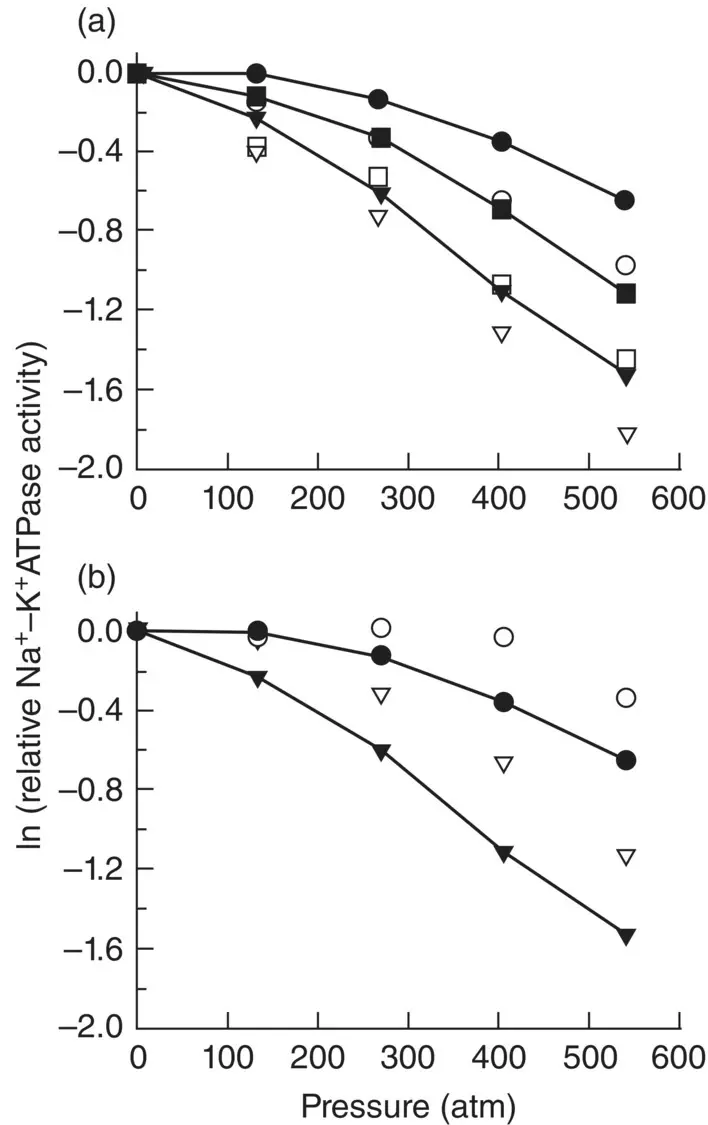

Figure 2.21 Effects of lipid substitution on the pressure responses of Na +, K +‐ATPase of three species of fish from different depth‐temperature habitats. Native membrane lipids were removed and replaced with (a) chicken egg phosphatidylcholine or (b) phospholipids prepared from the gill of the abyssal grenadier Coryphaenoides armatus . Filled symbols indicate pressure responses before lipid substitution; open symbols were assays after substitution. Circle symbols represent Coryphaenoides armatus (deep sea, cold habitat); square symbols represent the sablefish Anoplopoma fimbria (shallow, cold habitat); triangles represent the barracuda Sphyraena barracuda (shallow, warm habitat).

Source: Gibbs (1997), figure 6 (p. 257). Reproduced with the permission of Academic Press.

Oxygen

At all depths of the ocean, oxygen is removed from the water column as organisms respire and organic matter is biochemically degraded. Wave action, mixing, and photosynthetic processes replenish the lost oxygen in the upper mixed layer, but a zone of minimum oxygen forms at intermediate depth in all the world’s oceans. The severity of oxygen depletion in the minimum zones varies considerably, with values of dissolved oxygen ranging from 0 ml l −1(zero) in the Arabian Sea (Hitchcock et al. 1997) to about 4 ml l −1in the Antarctic (Smith et al. 1999) (see Chapter 1for plots of O 2vs. depth).

The major factors contributing to the persistence of oxygen minimum zones are global circulation patterns that result in the water at mid‐depths being out of contact with the atmosphere for hundreds of years. In areas where the water column is well‐stratified and rates of primary production are high, oxygen minima are especially severe. Dissolved oxygen values reach 0 ml l −1and stay near zero for hundreds of meters of water depth. Examples of such regions are the Arabian Sea, Bay of Bengal, Cariaco Basin, Philippine region, the northwest Pacific margin, and the eastern tropical Pacific. Hypoxic conditions in those areas extend from the bottom of the mixed layer to about 1500 m depth.

Although the oxygen concentration in oxygen minimum zones can be <0.2 ml l −1, large populations of organisms can reside there. Those organisms include the decapods, mysids, and copepods and even large populations of midwater (mesopelagic) fishes (Gjøsaeter 1984).

Organisms that inhabit oxygen minima exhibit a range of adaptations for dealing with hypoxic conditions. These adaptations include behavior, such as diel vertical migration out of the layer, in addition to unusual morphological and physiological characteristics (Wishner et al. 2000). Childress and Seibel (1998) have proposed three modes of adaptation to the oxygen minimum: (i) development of mechanisms for efficient removal of oxygen from water; (ii) reduction of metabolic rates; and (iii) use of anaerobic metabolism to compensate for the difference between aerobic metabolism and total metabolic needs. The use of anaerobic metabolism may occur on a sustained basis, during periods of high metabolic demand, or during transient periods spent in the oxygen minimum layer by vertical migrators.

The decreased food energy available in the deep sea (Vinogradov 1970) favors an aerobic existence where there is sufficient oxygen to be utilized. However, an oxygen minimum such as that in the Arabian Sea, where oxygen drops to zero, constrains species to an anaerobic existence while resident within it. Anaerobiosis poses a special problem to vertebrates. With the exception of breath‐hold divers such as marine mammals and turtles, most vertebrates, including fish, rely exclusively on aerobic metabolism and only switch to locally active anaerobic pathways during periods of increased activity or ambient low oxygen levels. For example, tuna white muscle is very well adapted for anaerobiosis, which is used during burst swimming (Hochachka 1980).

The main anaerobic pathway used by vertebrates is glycolysis, resulting in lactate production (Withers 1992). However, two major problems arise with use of the glycolytic pathway. First, the energy yield is very low, only 2 ATP per glucose as opposed to 38 ATP per glucose from aerobic metabolism. Second, the accumulation of lactate is potentially harmful to the organism. Build‐up of lactate can lead to osmotic imbalance, acidosis, and, ultimately, inhibition of glycolysis (Withers 1992).

Box 2.1 An Aside on Units

Oxygen is expressed in a variety of (nearly) interchangeable ways and those most commonly encountered in the literature have changed over the years. A few basics will help.

1. The total pressure of a gas mixture such as atmospheric air equals the sum of pressures exerted by each constituent gas. This is Dalton’s law.

2. Total (standard) atmospheric pressure is expressed as760 mm Hg (also known as “Torr”) or as 101 kilopascals (kPa), which is the SI unit for pressure.

3. The oxygen partial pressure in a standard atmosphere is the product of the mole fraction of oxygen in air × the barometric pressure:

PO2 = (0.2095) × (760 mm Hg) = 159.2 mm Hg (usually rounded up to 160 mm Hg)

PO2 = (0.2095) × (101 kPa) = 21.2 kPa (usually rounded down to 21 kPa)

4. Water in equilibrium with a gas mixture will have the same partial pressures as the gas mixture above it. This is Henry’s law. The snag is that the molar concentrations are a function of the partial pressures and an additional factor, the solubility coefficient. Thus: [ A ] = p A · α A

where [ A ] = mol l −1of A , p A = partial pressure of A (kPa), α A= solubility coefficient (mol l −1kPa −1).

5. Solubilities of oxygen in seawater decrease with increasing temperature and salinity. They are normally determined empirically (with exacting care!) at air saturation (e.g. Murray and Riley 1969) and compiled in a table for researchers to use. For Oregon waters ( Chapter 11), the oxygen concentration at 12 °C and 33‰ was used. It was reported as 6.14 ml l −1in Murray and Riley (1969). Knowing that a mole of oxygen is 22.4 l or 32 g, we can convert 6.14 ml l −1to 8.77 mg l −1(6.14/22.4) × 32. For future reference, to interchange ml l −1with mg l −1simply divide by 0.7. From there, it is a simple matter to convert to millimoles: 8.77/32 = 0.272 millimoles or 272 μmol kg −1, since the mass of a liter is a kg.

6. When comparing P cs across pelagic systems with widely varying temperatures and oxygen concentrations, it is easiest to use PO 2because the mole fractions do not change, but relative solubilities do.

Severity of Oxygen Minima, “Dead Zones,” and the Intertidal

It is important to appreciate the difference between oceanic oxygen minima, which are persistent, year‐round features located predictably in certain regions of the global ocean for millennia, and the seasonally appearing regions of hypoxia or “dead zones” like that at the mouth of the Mississippi River in the Gulf of Mexico (Rabalais et al. 1994) or in the deeper water of some Scandinavian fjords during summer (Diaz and Rosenberg 1995). The persistence and predictability of oceanic oxygen minima have allowed for adaptations in their resident fauna that enable a primarily aerobic existence. In contrast, the seasonally or episodically appearing anoxia of dead zones, as well as their duration and severity, precludes such adaptation. Infaunal species and any others with limited mobility experience 100% mortality in dead zones (Diaz and Rosenberg 1995). Life in both the oceanic oxygen minima and the episodic dead zones differs from the situation in the intertidal, where high intertidal species may experience anoxia twice daily but a return to normoxia is assured with the incoming tide.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Life in the Open Ocean»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Life in the Open Ocean» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Life in the Open Ocean» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.