Cees de Kom and I have something in common: we’re both what used to be called “halfbloedjes,” multiracial people with a black father and a white mother. The accepted term these days is “dubbelbloeden,” not half but double bloods, and no longer in the childish diminutive form. When I speak to Cees at events – most recently at a screening of a film about his father’s life – he never fails to point out this similarity between us. If anything in his life has left scars, it is being described as “half.”

Cees, born in 1928, was four years old when the family arrived in Suriname. After his father’s arrest, a crowd of protesters gathered in front of the administration offices to demand his release. The police opened fire. Two people were killed and twenty-two wounded. For more than three months, De Kom was held prisoner in Fort Zeelandia. By historical irony this was the very fort, built by the Dutch, where slaveholders could pay to have their so-called “disobedient slaves” disciplined. The Dutch colonists outdid both the English and the French in corporal and capital punishment; their methods included whipping, the cruel torture known as the “Spanish billy goat,” the breaking wheel, and death by burning. De Kom’s imprisonment must have added fuel to the fire of protest within him.

After he was exiled to the Netherlands, the intelligence service kept an eye on him. De Kom was seen as a communist, even though he never joined the Communist Party. He had tremendous difficulty finding work. “I remember my father was always writing,” Cees tells me, “wearing his pencil down to a stub to save money. When World War II broke out, he joined the resistance and wrote for the illegal press. On August 7, 1944, he was arrested by the Germans. My mother sat looking out of the window for hours, hoping he would come back. But he never came. My brother and I were deported to Germany, where we worked on a farm.

“After we returned, we were told we had to leave again, this time to the Dutch East Indies. Restoring law and order there, that was our mission. And my father had sympathized with the Indonesian freedom fighters! I wrote a letter to the minister of defense asking for an exemption. My mother hadn’t heard from my father since the liberation of the Netherlands. The most recent news we had was that he was being held in the German concentration camp Neuengamme. I didn’t want to leave my mother until we found out what had happened to him, but that argument cut no ice with the Dutch authorities. Not until 1950 were we officially informed that my father had died in a camp on April 24, 1945.” Cees points into the living room. “And my mother died in that chair right there – just gave up the ghost. We’d been living in Suriname for years by then, and she was visiting on vacation.” A while ago, he decided the time had come to write his own memoirs: “All the dead weight you carry around.” He hands me a thick manuscript in a ring binder. Two Cultures, One Heart is the title; underneath is a drawing of two overlapping circles, his parents’ wedding rings.

“In the Netherlands, my name was written the usual Dutch way, with a K. I changed the spelling to Cees, which seemed more elegant to me, less Dutch, because in the Netherlands I could find no trace of my Surinamese culture.”

As a boy, he was once on a tram with his father when a woman pointed out Anton to her child with a nod of the head and said, “Look, that’s the bogeyman. Watch out, or he’ll come and get you.” There were also children who taunted Cees: “You don’t have to buy soap, ’cause you’ll always be dirty anyway.” Later, still in the Netherlands, he worked for the PTT – the state postal, telegraph, and telephone service. One day he was discussing cultural differences with his co-workers, and a Dutch co-worker made the clumsy remark, “To people in Groningen I speak with an accent too, you know.” On August 18, 1960, when his father’s remains were reinterred in Loenen, the field of honor for those who died as a result of the war, all the names of the dead were read aloud except De Kom’s. They were later told this had been a technical problem.

“One dirty trick after another,” Cees says with a sigh. Always inferior, always misunderstood – he was sick and tired of it. Six years later, he and his family departed for his father’s country on the ship Oranje Nassau . It was the same voyage his parents had made some thirty years earlier. But even in Suriname, as he discovered, the country’s unique identity is often underappreciated. “Almost all the books read here come from the Netherlands.” The family, through a non-profit, owns the house where Anton de Kom was born, but they do not have the money to restore it. The government has neglected it altogether.

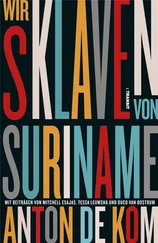

To throw off the yoke of Dutch rule – that was De Kom’s aspiration when he wrote the book that has now become a classic: “No people can reach full maturity as long as it remains burdened with an inherited sense of inferiority. That is why this book endeavors to rouse the self-respect of the Surinamese people” (p. 85). In 2020, the forty-fifth anniversary of Surinamese independence, those words are as true as ever. In We Slaves of Suriname , De Kom was far ahead of his contemporaries – not only in Suriname, but also in the Netherlands. The land that the Netherlands had ruled for more than three hundred years would long remain a colonial blind spot. Only in the past few years has Suriname gained a modest place in Dutch collective awareness. This change is taking place in fits and starts, and the historical narrative coming into the spotlight is not always a pretty one.

When I was growing up in Amsterdam in the 1970s, I wrote a letter to the editors of my favorite girls’ magazine, Tina . I was twelve years old. In my childish handwriting, I complimented them on their work and asked, “Why isn’t there ever a colored girl on the cover?” Every day, I checked my mailbox for a reply. The fact that I never received one wounded me deeply.

Anton de Kom’s work stands out both for its profound eloquence and for the courage with which he points out injustices. It is a tirade against the pragmatic spirit of commerce, the small shopkeeper’s mindset that underlay the exploitation of a country and its people. Though its story is not by any means heartwarming, it is the story we share. The Dutch fathers of the colony boozed, fucked, and flogged with abandon, partly out of boredom and frustration with the tedium of plantation life. Such decadence would have been unthinkable in their own strait-laced homeland.

As a Surinamese schoolboy, De Kom had learned about Dutch sea rovers such as Piet Hein and Michiel de Ruyter and been required to memorize chronological lists of the colony’s governors, the very men who had imported his African forefathers in the holds of slave ships. In his own book, he delves deep into the psyche of the slaveholders. He is hot on their trail, breathing down their necks, not letting up for a moment. You can practically see De Kom writing: perched on the edge of his chair, craning forward, pressing his stubby pencil to the paper. His style is supple, essayistic, and now and then lyrical, with unexpected imagery. Using the writer’s toolkit, he infuses his work with color and emotion. And not once does he forget his own background, so aptly expressed by his use of an odo, a Surinamese proverb: the cockroach cannot stand up for its rights in the bird’s beak.

When did the cover-up of this history really begin? For many years, anyone who brought it up could count on a patronizing response, something along the lines of “But look what the French or the British did, or the Africans themselves!” It’s like the excuses made by buyers of stolen goods when caught red-handed. They point an insistent finger at the thief and the fence: it was them , not me ! Yet without demand, there would be no supply. In a few places, monuments are being erected to commemorate the suffering, and explanatory labels are being placed next to statues of disgraced role models. But turning around and looking your own monster straight in the eyes still takes some effort.

Читать дальше