polity

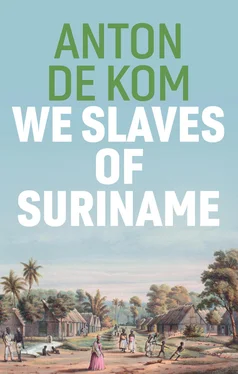

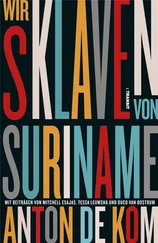

Wij slaven van Suriname © 1934/1983/2020 by Anton de Kom

© Introductions by Tessa Leuwsha, Mitchell Esajas, Duco van Oostrum (2020) and Judith de Kom (1983)

Originally published in Dutch as Wij slaven van Suriname by Uitgeverij Atlas Contact, Amsterdam.

This English edition © Polity Press, 2022

This publication has been made possible with financial support from the Dutch Foundation for Literature. The publisher gratefully acknowledges the support of the Dutch Foundation for Literature.

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

101 Station Landing

Suite 300

Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-4901-6 (hardback)

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-4902-3 (paperback)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021942476

by Fakenham Prepress Solutions, Fakenham, Norfolk NR21 8NL

The publisher has used its best endeavors to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Warning: This note mentions denigrating terms that express racist attitudes and may offend or upset some readers .

Although De Kom’s writing was in many respects ahead of its time, he uses terms for race and skin color that now seem quite dated and may occasionally confuse today’s readers. Rather than forcing him into a twenty-first-century mold, I have looked to English-language writing of the 1920s and 1930s for equivalents: books by Richard Wright, Zora Neale Hurston, and C.L.R. James.

These authors use the term “Indian” to refer to the indigenous peoples of both the Americas and the Indian subcontinent. Adjectives are often used to disambiguate, e.g. “Red Indian” and “British Indian.” (The term “West Indian,” used for all inhabitants of the West Indies regardless of race, adds another degree of complexity in James’s writings.) De Kom refers to the indigenous peoples of South America simply as “Indianen,” rendered here as “Indians,” or by terms such as “inheemsen” (“natives” or “indigenous people”), or often by the names of their specific peoples. He refers to the people of British India and the Surinamese people descended from them as “Brits-Indiërs” (“British Indians”), “Hindoestanen” (“Hindustanis”), and in two places “Hindoes” (“Hindus”).

Like Wright, Hurston, and James, De Kom is sparing in his use of capital letters in terms for race and skin color, using lower-case letters for the equivalents of “black,” “white,” “colored,” “maroon,” and “creole.” I have followed his example. De Kom also writes the Dutch term “neger” with a lower-case letter, but I translate this as “Negro” with a capital “N,” after my English-language models. This reflects the pride and self-respect with which De Kom uses the term “neger” and the distinct contrast with the highly offensive term “nikker” (rendered as “nigger”), which he reserves for expressions of the racism of the typical white colonist. “Neger” has become such a fraught term in contemporary Dutch that De Kom’s use of the word can be confusing or upsetting to twenty-first-century readers. “Negro” is actually less problematic in this respect; although it is now outdated, it is not generally seen as a term of abuse. In the introductions, the slightly different capitalization conventions reflect authorial preference and contemporary usage.

Some literary translators and other writers have recently argued that the use of italics for words regarded as foreign is an inherently racist or chauvinist practice, in that by drawing and emphasizing an absolute distinction between the native and the foreign, it reinforces invidious notions of cultural, national, and racial purity. I believe the intent and effect of this conventional use of italics vary from writer to writer and from book to book, but there can be no doubt that De Kom generally avoids italicizing “foreign” words, especially words from the Sranantongo language, and that this choice emphasizes the integrity of his distinctively Surinamese idiom. I have done the same in English but included a glossary of Surinamese terms in the back of the book, so that readers unfamiliar with Sranantongo and Surinamese idiom can better follow De Kom’s vivid descriptions of his country. Where Sranantongo or other foreign terms are glossed in the main body of the book, the glosses were introduced by De Kom. I have adopted modern Sranantongo spelling throughout the book (with the indispensable aid of Professor Michiel van Kempen), both for the sake of readers familiar with Sranantongo and to improve readability and usability for readers who do not speak the language but might wish to learn more. I hope De Kom would have approved of this choice and felt, as I do, that it disentangles his work from the spelling conventions of the Dutch colonial power.

When De Kom first published his book, it was not edited to today’s professional standards, and Dutch editions up to the present day have remained largely unchanged in this respect. De Kom was a political activist and a writer rather than a professional historian, and his access to research materials was severely limited; he had to rely heavily on a few main sources, mostly secondary works that quoted at length from primary sources. For these reasons, some proper names and titles contain obvious errors, and many names are given only in part (often the surname only). While this is not a critical or scholarly edition, I have attempted, with much-valued assistance from Professor G.J. Oostindie and Professor Van Kempen, to correct such errors and fill in missing names where possible. No doubt some errors remain, and I apologize for any that I have unintentionally introduced.

De Kom included both a scholarly apparatus of endnotes and a few footnotes defining terms or offering additional context. In this edition, his two sets of notes have been merged into a single series of endnotes. I have added a number of translator’s notes, often intended to clarify cultural references that might otherwise puzzle modern English-speaking readers; these too can be found among the endnotes, marked with “Translator’s note” or “TN.”

I am grateful to Professors Oostindie and Van Kempen, David Colmer, Professor Gloria Wekker, Dr. Duco van Oostrom, Tessa Leuwsha, and Lucelle Pardoe for their insightful input, which made a tremendous difference to the final version. My thanks also to the Dutch publisher Atlas Contact, particularly Hayo Deinum, for taking the initiative for an English-language edition, to Mireille Berman and others at the Dutch Foundation for Literature for their financial and institutional support for the project, and to Elise Heslinga, John Thompson, Susan Beer, Evie Deavall, and their colleagues at Polity Press for publishing this English-language edition and giving me the opportunity to translate it. I was very fortunate to be in the right position at the right time to translate this book for publication; others who have done much more than I to promote De Kom’s legacy, such as Professor Oostindie and Dr. Karwan Fatah-Black, deserve special mention here. Finally, a generous 2021 ICM Global South Translation Fellowship award from the Institute for Comparative Modernities at Cornell University enabled me to devote additional time to the daunting task of writing a translation worthy of De Kom’s landmark book.

Читать дальше