Introductions

I am in the Frimangron district of Paramaribo, standing in front of the birthplace of Anton de Kom. It’s a corner building. On the sidewalk in front of the house is a memorial stone with a quotation from the famed Surinamese resistance leader: “Sranan, my fatherland, one day I hope to see you again. The day all your misery has been wiped away.” Less than fifteen feet behind the stone, the two-story wooden house looks broken down. Drab vertical beams hang askew from nails, and part of the zinc roof has caved in. One window shutter is open, a curtain pulled aside; this is still someone’s home. Beside it, a plantain tree half-conceals the low house next door. Down the walkway between the two homes, a skinny black man comes out of the backyard. His hair and beard are gray. His T-shirt is too big for him; so are his flip-flops. Holding a flower rolled up in newspaper, he sits down on the stoop in front of the former De Kom family home. I’m curious who the flower is for. He pays no attention to me – so many people take photos here.

In the 1930s, hundreds of people stood waiting here to speak to Anton de Kom. Many were unemployed; others were workers struggling to survive on meager wages. After the abolition of slavery in 1863, the Dutch authorities had rounded up indentured workers in what were then British India and the Dutch East Indies to work on the plantations of Suriname. Later, when the agricultural economy went into decline, those workers had followed in the footsteps of the once-enslaved people, flooding into the city to find work. But Paramaribo, too, was riddled with poverty. They hoped for a chance to sit down at the little table in the back garden with the man who had returned from Holland with a fresh wind of resistance.

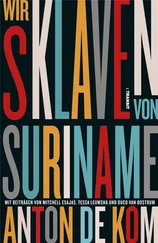

Cornelis Gerhard Anton de Kom was born in Paramaribo in 1898. He earned a degree in bookkeeping and worked for a while at the offices of the Balata Compagnie, which was in the business of harvesting balata, a kind of natural rubber. De Kom was struck by the difficult lives of the balata bleeders: laborers, mostly creoles (the term then in common use in Suriname for the descendants of freed slaves), who tapped the rubber trees in the stifling heat of the rainforest. He resigned and, in 1920, left for the Netherlands, where he married a Dutch woman, Petronella Borsboom.

As one of the few people of color in the country, De Kom came into contact with Javanese nationalists who were fighting for an independent Dutch East Indies: in other words, for Indonesia. That was when he first felt the winds of freedom blowing. He began to write articles for the Dutch Communist Party magazine; at the time, that was the only party with a clear anti-colonial stance. His articles and the revolutionary thrust of his arguments caught the attention of the Surinamese labor movement. He was especially popular with that group for criticizing wage reductions for indentured workers.

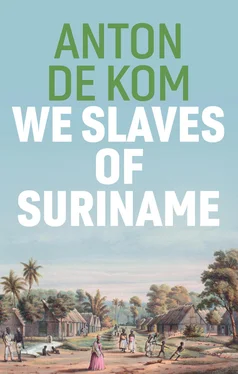

In late 1932, De Kom and his wife and children, four by then, returned to Suriname by ship to look after his ailing mother – who died during their voyage. Like-minded Surinamers were eagerly looking forward to De Kom’s visit. In the backyard of his childhood home, he set up an advisory agency and took meticulous notes on his visitors’ grievances. The Javanese, who felt disadvantaged relative to other ethnic groups, were the most likely to turn to “Papa De Kom,” as they soon began to call him. Their heartfelt wish was that De Kom would lead them back to Java like a messiah. He wrote about them in We Slaves of Suriname : “Under the tree, past my table, files a parade of misery. Pariahs with deep, sunken cheeks. Starving people. People with no resistance to disease. Open books in which to read the story, haltingly told, of oppression and deprivation” (p. 203). De Kom promised to submit their grievances to the colonial authorities, but the unrest he caused was anything but welcome to Governor Abraham Rutgers.

On February 1, 1933, Anton de Kom led a group of supporters to the offices of the administration. He was arrested on suspicion of attempting to overthrow the regime.

From the street, none of the backyard is visible. The sidewall of the house is completely covered with zinc, and a large mango tree leans on the roof. In front of the neighboring house on that side, a woman is raking the fallen leaves and fruit into a pile. She is wearing a pink skirt, a tight sweater, a cap, and dark glasses. Like many people here, she probably bought her outfit from one of the cheap Chinese clothing shops found all over Paramaribo. The few with more to spend buy their clothes abroad or online. In some respects, today’s city remains much like the Paramaribo in which De Kom grew up in the early twentieth century – even if the rich no longer live in the white-and-green mansions in the historic center, but in modern stone villas in leafy suburbs with names like Mon Plaisir and Elisabeths Hof.

It is not surprising that a revolutionary such as De Kom had his roots in a working-class district like Frimangron. In the days of slavery, enslaved people who had managed to purchase their freedom settled on the undeveloped outskirts of the city. Before then, emancipated house servants had made temporary homes in slave hovels in the backyards of Paramaribo’s mansions. Frimangron literally means “freed people’s land.” On the long sand roads, the new citizens built simple dwellings and practiced trades. The main traffic artery was Pontewerfstraat. From its small workshops came the sounds of carpenters sawing and cobblers pounding and tapping, of tanners and tinsmiths. The women there did laundry or ironing for the white and light-skinned elite who held the power in the Dutch colony. This street, renamed after Anton de Kom in the early 1980s, is the location of the house where he was born.

De Kom must have spent a good deal of time as a child on the very stoop where the elderly man is now sitting. His father had been enslaved, and his grandmother taught her grandchildren about “the sufferings of slavery,” in the words of De Kom’s fierce indictment We Slaves of Suriname . He published the book in 1934, a year after the colonial authorities banished him from Suriname.

De Kom was a quick student and must have learned from a young age not to take injustice for granted. Many children in his neighborhood went barefoot, wore rags, and roamed the streets after dark. Education was compulsory, but few parents could afford the school fees, let alone decent shoes and school clothes. They had a hard enough time giving their children a simple meal, such as rice and salt fish, every day. If they could, they sent their children to work as kweekjes, sweeping, raking, and lugging pails of water for a wealthy family in return for room and board. Child labor was rife.

Anton de Kom’s own childhood was probably easier. His father scraped together a living from his patch of soil and also worked as a gold miner. Young Anton must now and then have passed through Oranjeplein, a stately square in the alien realm of the city center, where the statue of Queen Wilhelmina stood in front of the governor’s magnificent palace, although the monarch never visited her colony. Under the tamarind trees around the square, the upper middle class promenaded in their walking suits and long white dresses. In Frimangron, everyone was black. That is still mostly true today.

One Sunday morning, I drive down Anton Dragtenweg, along which handsome houses overlook the Suriname River. My destination is the district of Clevia: tight rows of Bruynzeel houses, mass-produced modular wooden dwellings with front and backyards. I park beside a recently sanded fence. “I’m painting the gate,” Cees de Kom told me on the telephone, sounding a little breathless. Anton de Kom’s son is now ninety-one years old but still looks sprightly. He invites me to walk up the stairs to the balcony ahead of him. His wife, one year younger, shakes my hand just as energetically.

Читать дальше