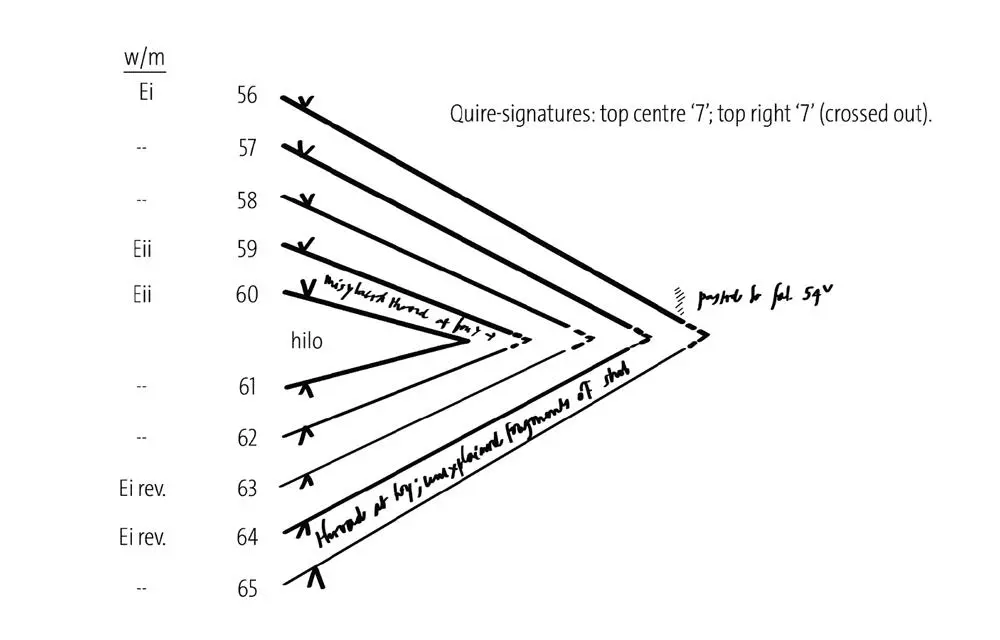

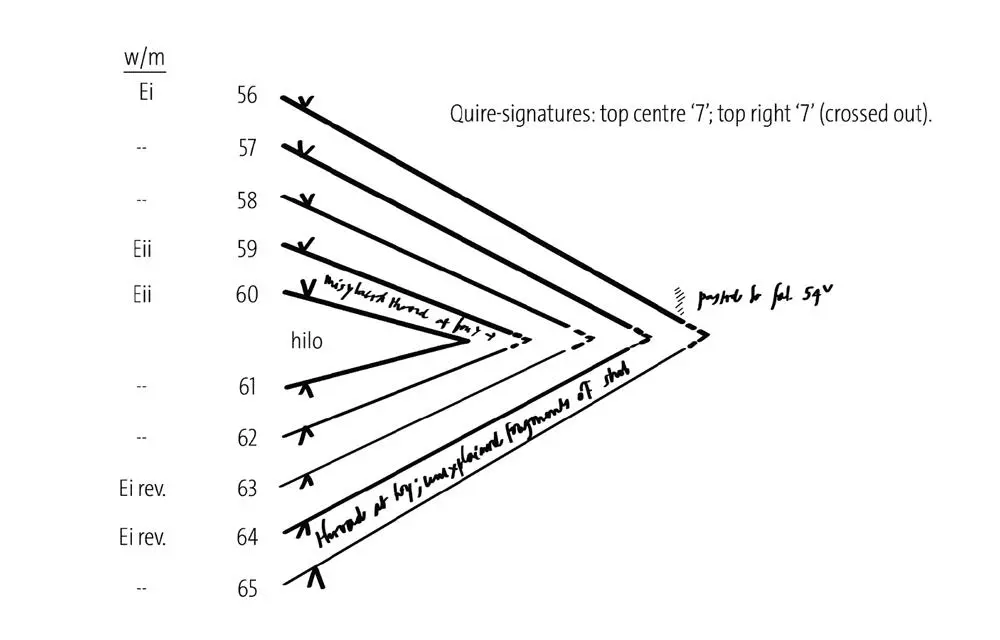

Chart 14. Quire VII, reconstruction A

Quire VII, reconstruction A

This reconstruction accepts that the structure of folios 56-65 is a regular quire of ten leaves, but fails to explain the stub between 64 and 65 except through some unspecified effect of the later disturbances.

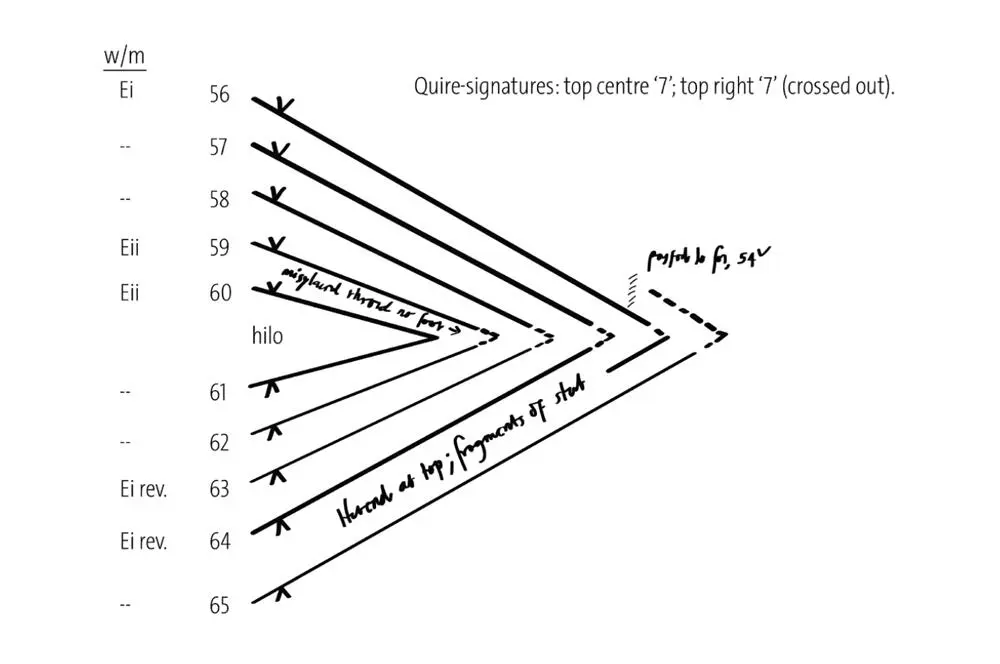

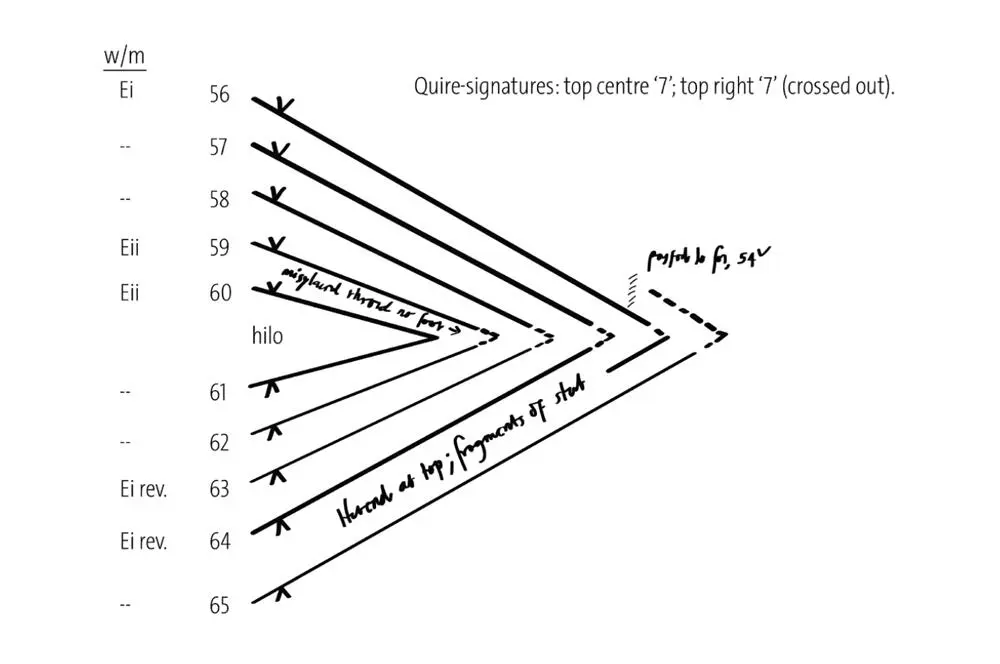

Quire VII, reconstruction B

Assuming that there is no textual disturbance between folios 64 and 65, this reconstruction assumes a similarly regular structure of bifolia in a quire of ten leaves, except that the original conjoint mate of folio 56 was eliminated after folio 64 and that the present folio 65 was an immediate replacement.

Chart 15. Quire VII, reconstruction B

Note: Folio 65 is creased and bunched at the tail of the gutter, while folio 56 shows no parallel disturbance in the equivalent area. However, the picture-cycle and text appear continuous from folio 64 to 65.

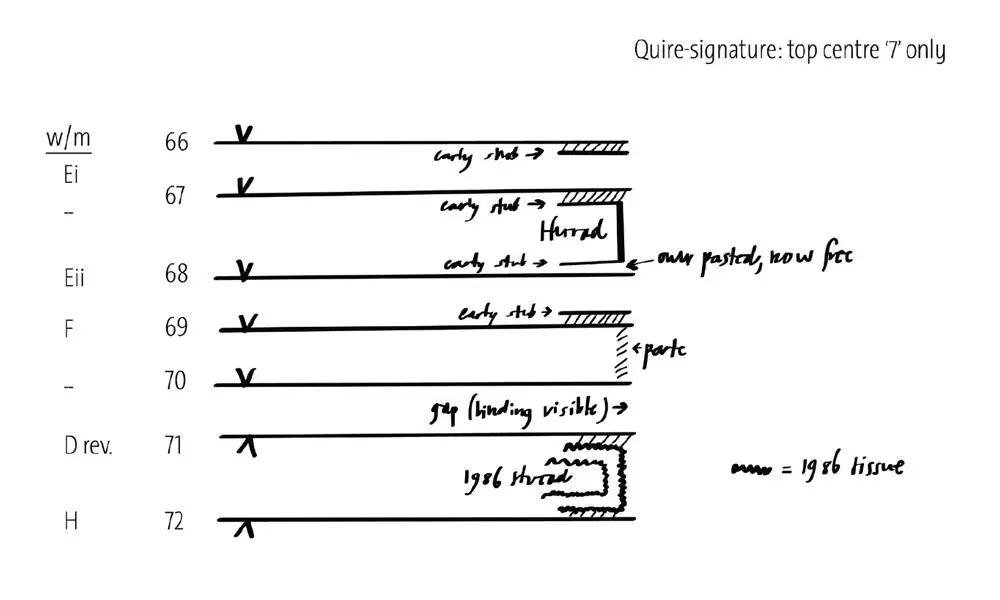

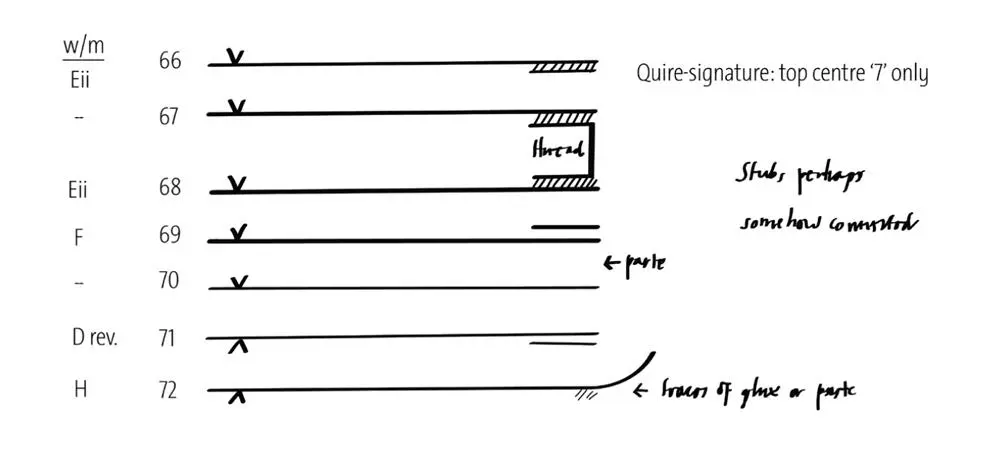

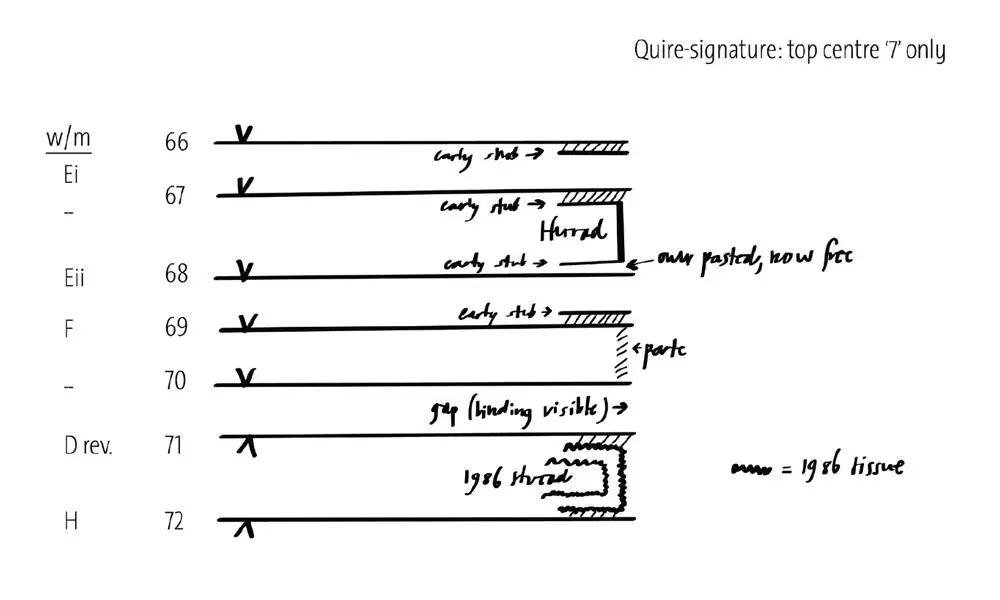

Quire VIII, state after the repairs of 1986: visible evidence only

By 1986, the last leaf of the Codex Mendoza (folio 71) and the following blank leaf (folio 72) were detached. In the repairs of 1986, repairing tissue was used to create an artificial bifolium out of these folios, which was subsequently sewn into the codex. The thread is surrounded by an additional free-standing fold of tissue. This necessitated setting folio 72 further out, making its old sewing holes and conjoint stub clearly visible. The stub at the gutter of folio 68r was released (but left in place), and the underlying surface was repaired with tissue.

Chart 16. Quire VIII, state after the repairs of 1986: visible evidence only.

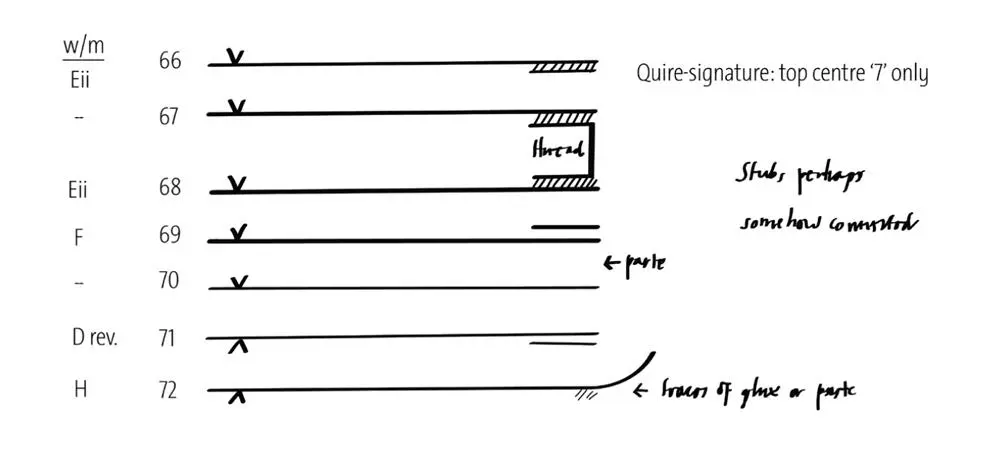

Quire VIII, presumed earlier state, after the seventeenth-century rebinding

As in Quire VI, the seventeenth-century structure was artificial. Every leaf except folio 70 (and perhaps 72) was lined at the gutter with a stub of the familiar early repairing paper. The stub at folio 71v is visible both in the 1938 Cooper Clark facsimile and (though perhaps already slightly modified in shape) in the transparency made in 1985 for the 1992 facsimile. It was removed in 1986 and replaced with lighter tissue. The stub at folio 68r was released in 1986, but the rest are still stuck down. Like folios 55 + 53, folios 67 + 68 are artificially joined by a fold of the old repairing paper to form the central bifolium of the made-up quire with a thread at the gutter. However, it is now impossible to tell exactly how the stubs of folios 66v, 69r, and 71v were joined up to fit into the artificial structure. There is no sign of an old stub on either side of folio 70, but its recto is pasted at the gutter onto folio 69v.

The blank leaf, folio 72, carries old sewing holes which are similar in kind and partly in position to those of folios i-ii. The old sewing holes of folio 72 differ from the positions of those of the seventeenth-century binding. Although it carries a different watermark, folio 72 probably dates from the same period as folios i-ii and fulfilled the same function as a flyleaf at the end of the Codex Mendoza. It now serves as a blank separating the Codex Mendoza from the second part of the volume. Originally, it was set deeper into the sewing, with a fairly broad stub which perhaps folded around or into Quire VIII; the area of its former fold carries traces of discoloration which could indicate that it was once lined on the outside with a fold of repairing paper, though nothing of this now remains.

Chart 17. Quire VIII, presumed earlier state, after the seventeenth-century rebinding

It is striking that the seventeenth-century quire signature, properly “8” in the sequence, is not visible at the top right of folio 66r (there is a possible erasure at about the same place, but yielding nothing under ultra-violet light). Its absence or erasure could imply that, in that system, these final leaves were regarded as part of the preceding quire (Quire VII). If so, this might suggest that the seventeenth-century binder had somehow been manipulated to attach these leaves together to yield a large quire of folios 56-65 + 66-71 + ?72. Given the artificiality of such a structure (chart not attempted), this might still be possible even with two sets of threads, as now visible between folios 60-61 and 67-68. However, it is dangerous to base too much on the negative evidence of a missing quire signature.

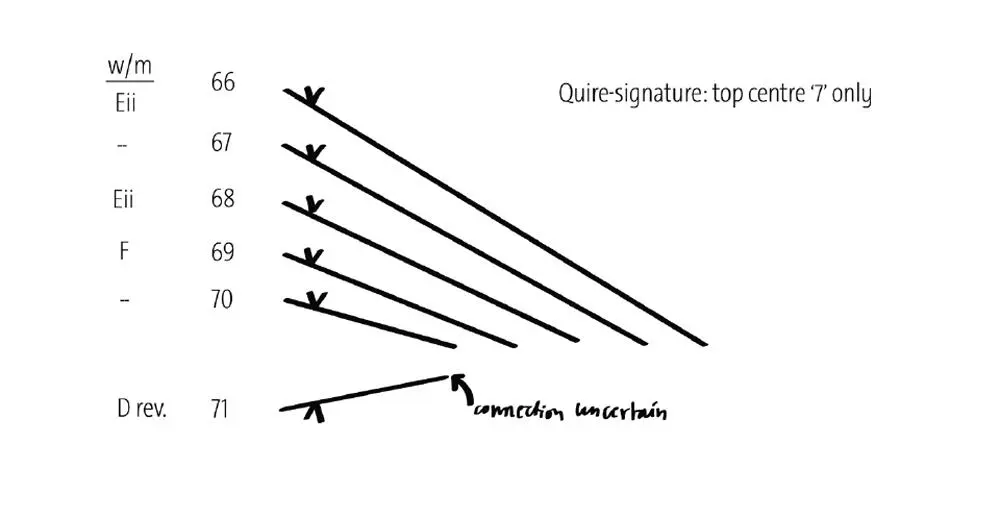

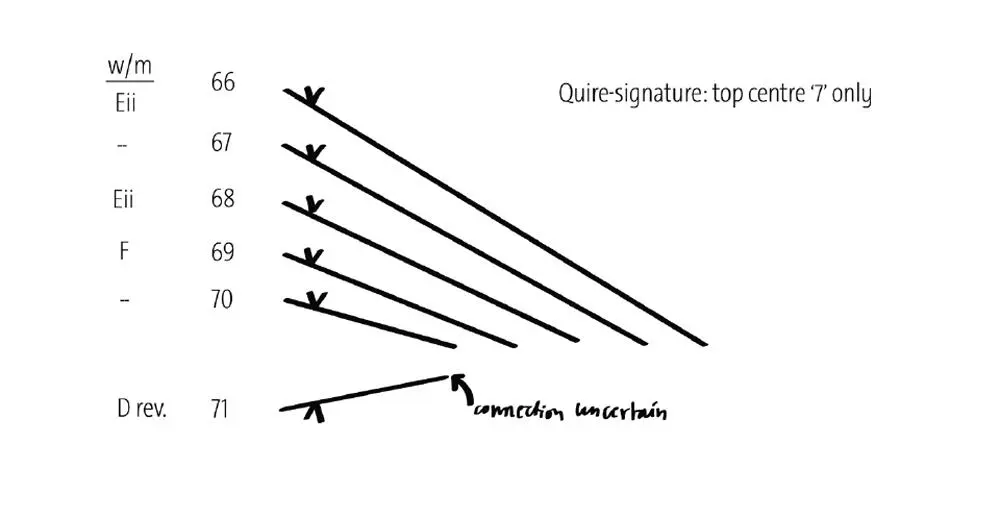

Original structure of Quire VIII: hypothetical reconstruction

The direction of mold and felt sides show that none of the five leaves from 66 to 70 could have been conjoint with each other and suggest that Quire VIII resembled earlier quires in its original structure (e.g. perhaps it was originally a ten-leaf quire with folios 66-70 as the first five leaves, all with their rectos as “mold” sides). The earlier system of quire signatures yields the “7”-shaped sign as usual at the top center of folio 66r (this time without the later quire signature, as explained above). The last original leaf, folio 71 (“mold” side at verso), reintroduces a pilgrim watermark (Pattern D), but in yet another subvariety. The only leaf with which folio 71 is at all likely to have been conjoint is folio 70, though there is some difference in texture (perhaps due to the later damage).

Chart 18. Original structure of Quire VIII: hypothetical reconstruction.

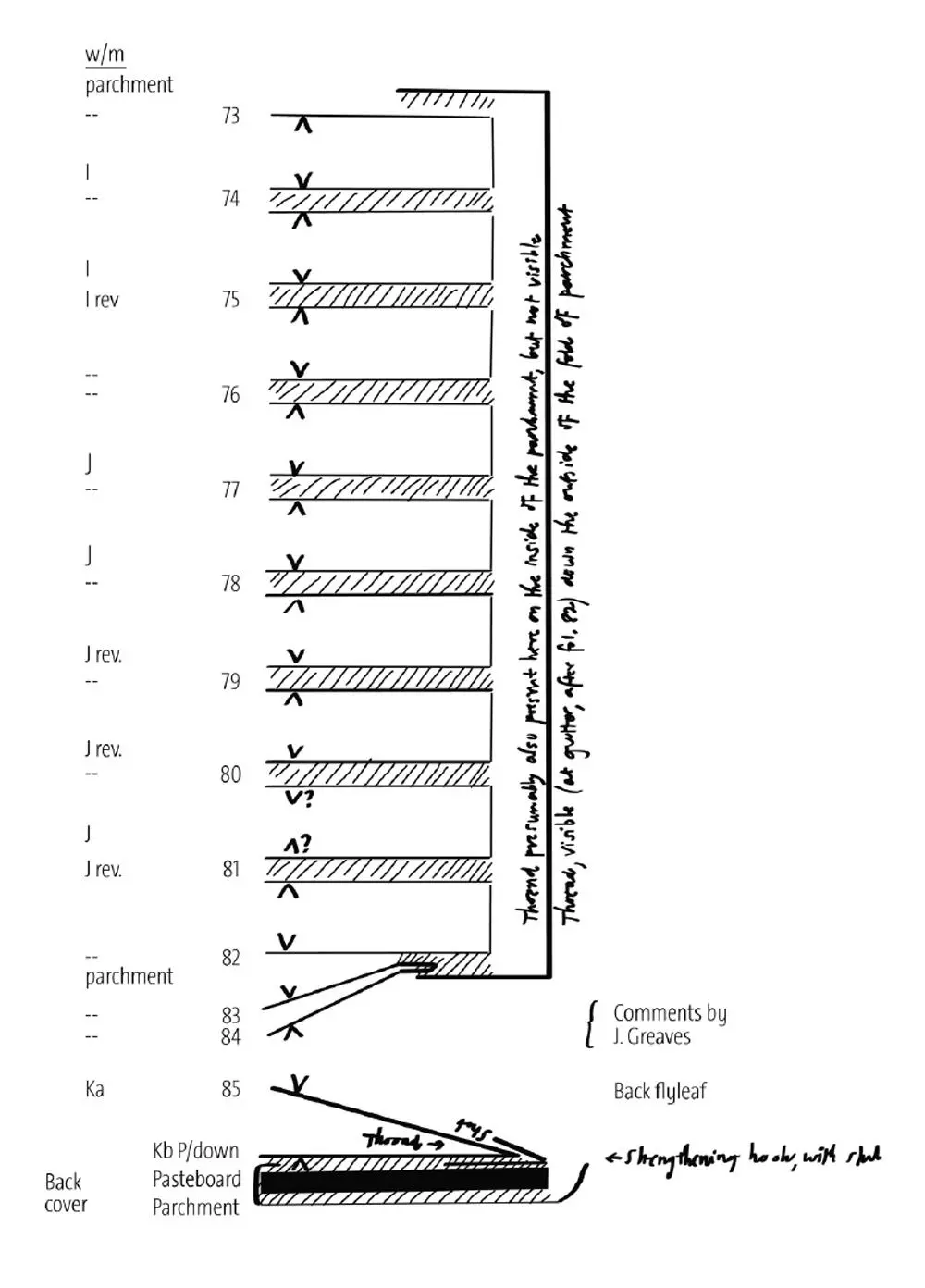

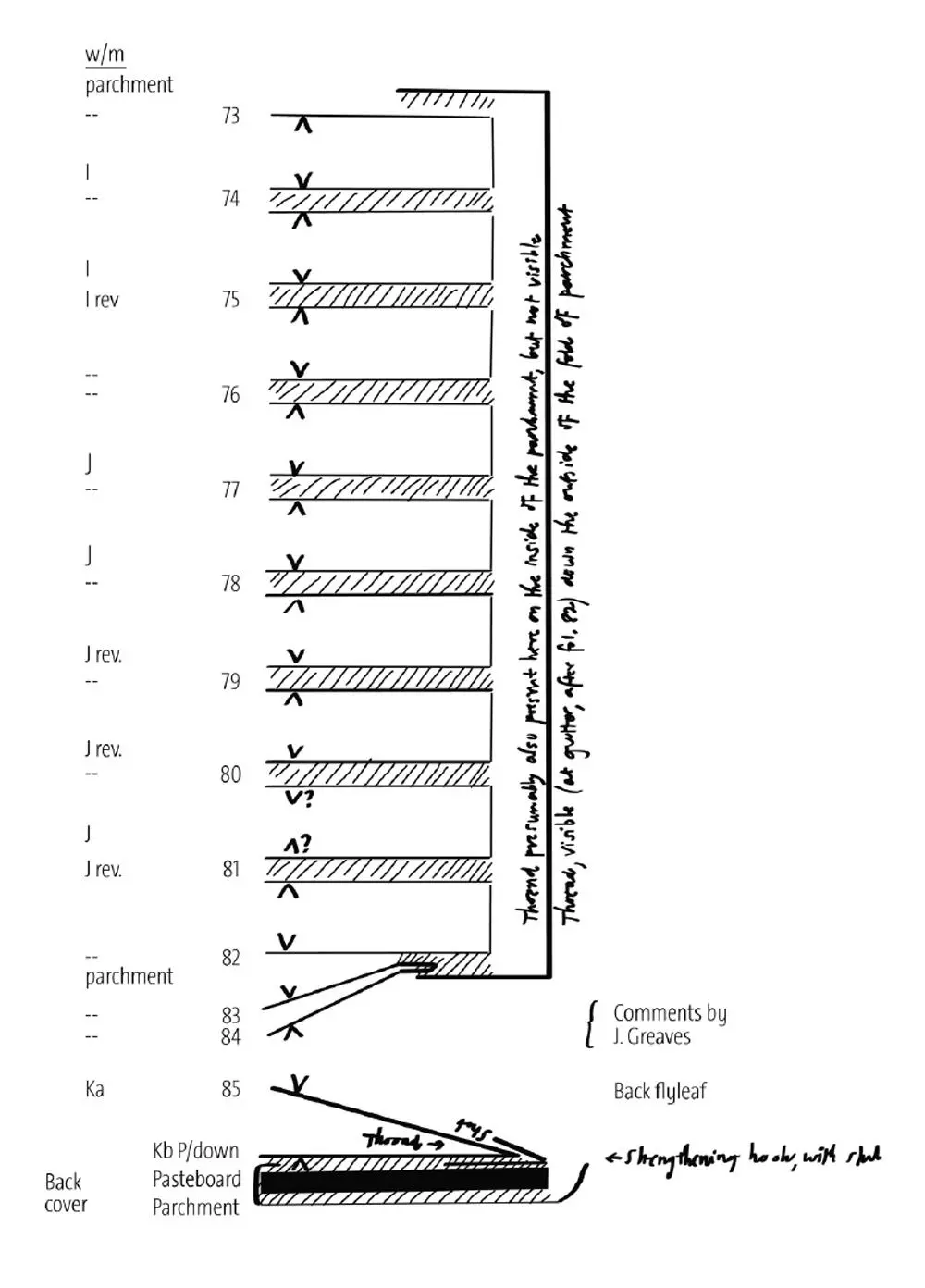

Part 2 (folios 73-85):

Monetary tables and lower endpapers

The tables illustrate the comparative value of Roman and Greek monetary standards against their English and French equivalents of the later sixteenth century. The headings are in English and English silver of 1563 is mentioned in the first table (folios 73v-74r).

Each of the nine tables was written across a single large sheet; the first six are numbered 1-6 in early ink in the lower right corner. The tables were then folded and pasted together, as below, to form a clumsy booklet within a narrow fold of parchment. A note about the tables, on a smaller bifolium (folios 83-4 with no watermark), was kept with them; in this note, John Greaves questions whether, in view of their errors, the tables were really those created by Sir Thomas Smith praised in Camden’s Elizabeth.

Chart 19. Part 2 (folios 73-85): Monetary tables and lower endpapers

Codex Mendoza: Summary reconstruction of binding history3

First stage (1540s-1560s?)

Jerónimo López reported having seen a volume “with covers of parchment”, similar to and perhaps identifiable as the Codex Mendoza in the home of the Indian master-painter Francisco Gualpuyogualcal around 1541 (Nicholson 1992a, 1–2).4 However, the identification of that book as the Codex Mendoza is disputed. The Codex Mendoza itself offers no physical evidence for the existence of a binding in the first three decades or so of its existence (before and immediately after its passage from Mexico to France), but instead may rather contain some clues indicating that it had survived in a disbound condition.

Читать дальше