In Reconstruction A, the regularity of the quire was disrupted from the start, for unexplained reasons: folios 1-2 formed a separate pair of leaves (perhaps a conjoint bifolium) and folios 9-10 were two singletons which could never have been conjoint. A factor in favor of this version is that the texture of folio 1, somewhat coarse and thick, seems to match that of folio 2 better than that of folio 10; however, this effect could have been caused by the additional wear and tear to the first two leaves.

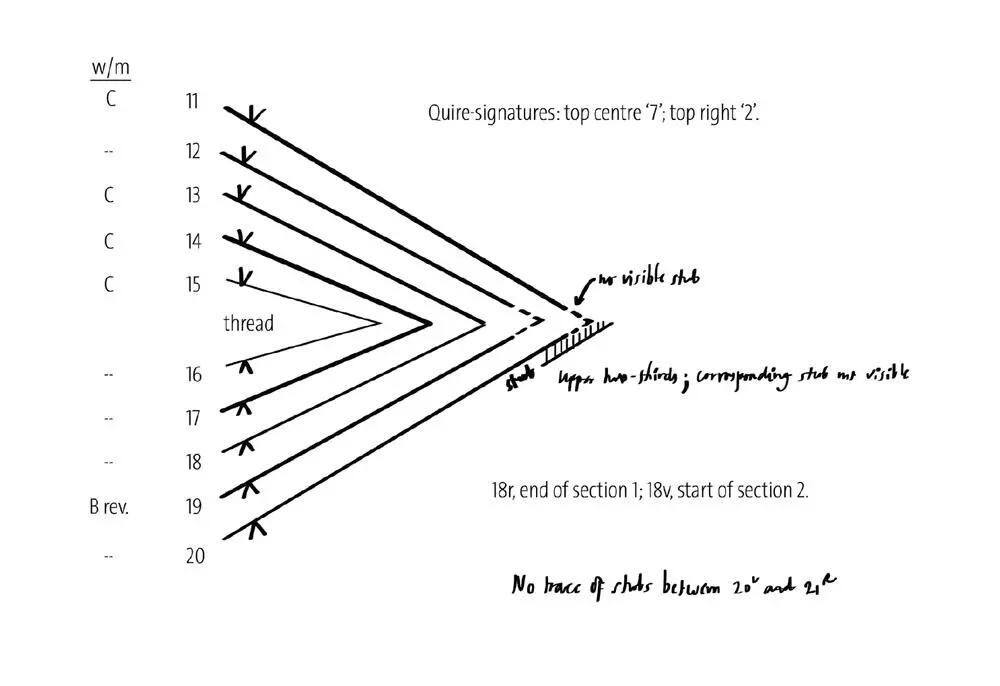

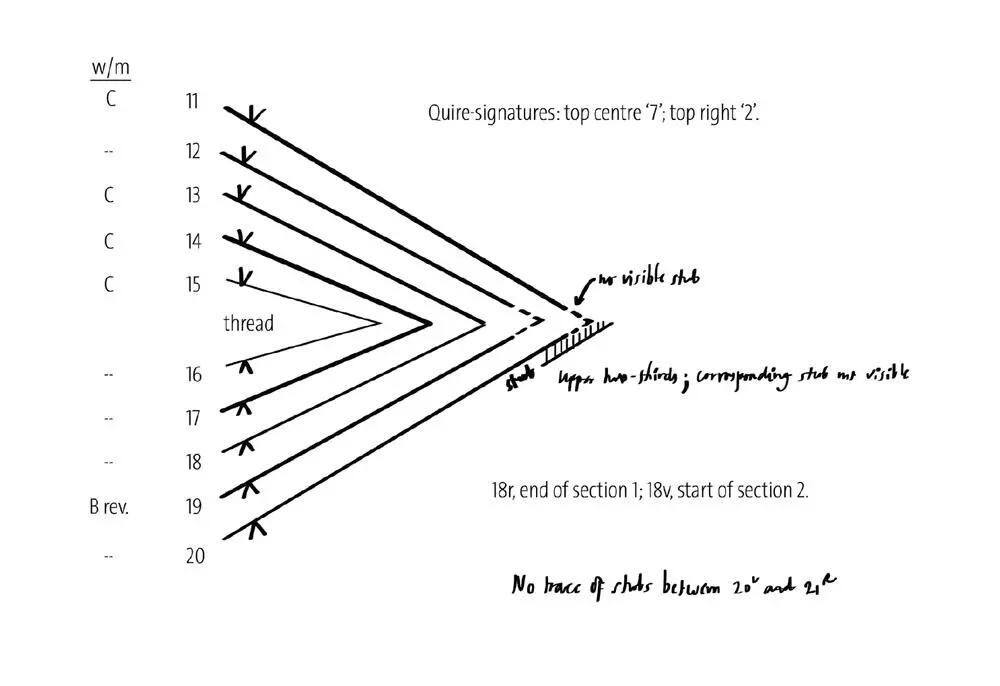

Chart 7. Quire II

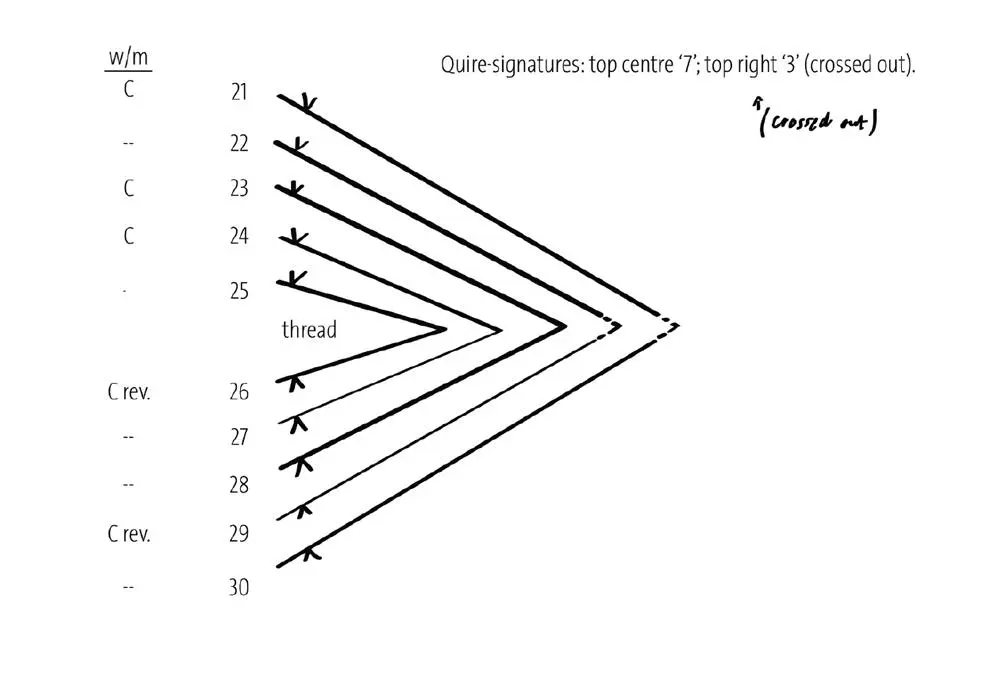

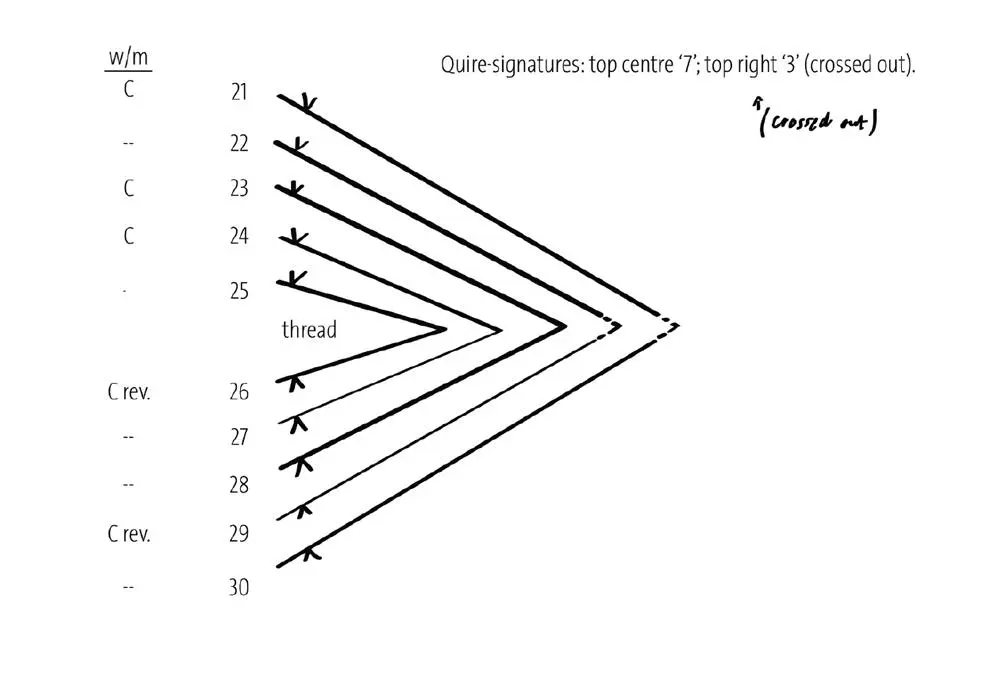

Chart 8. Quire III

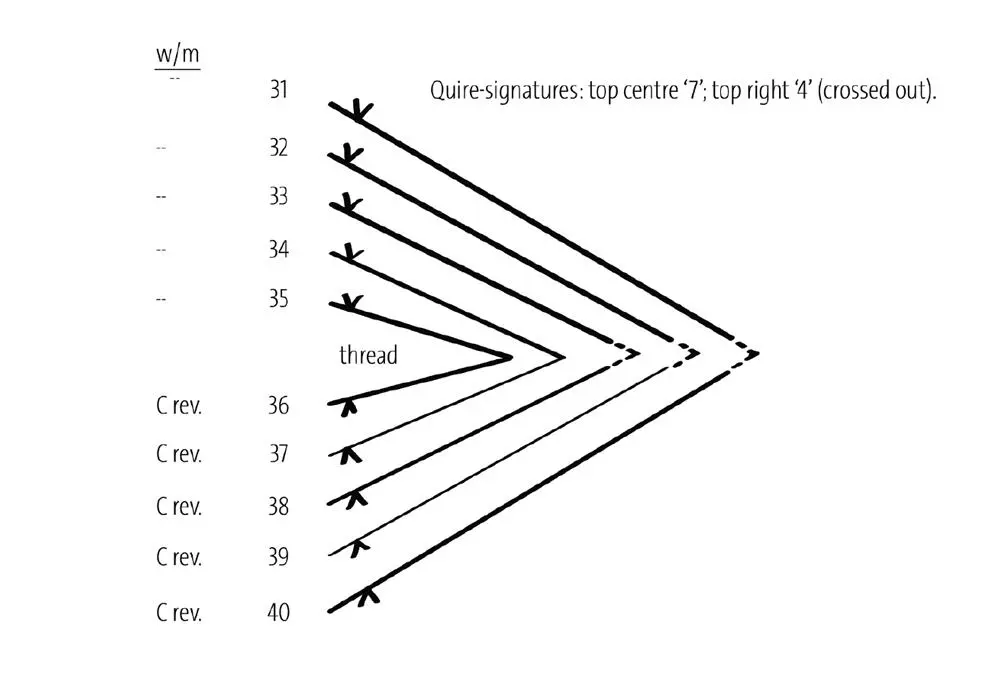

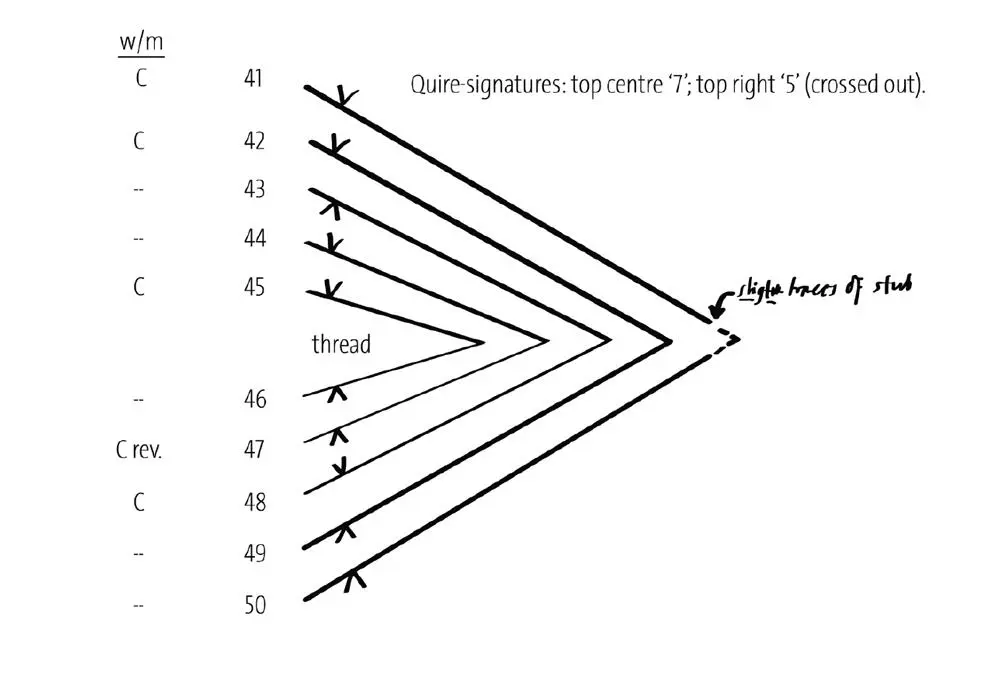

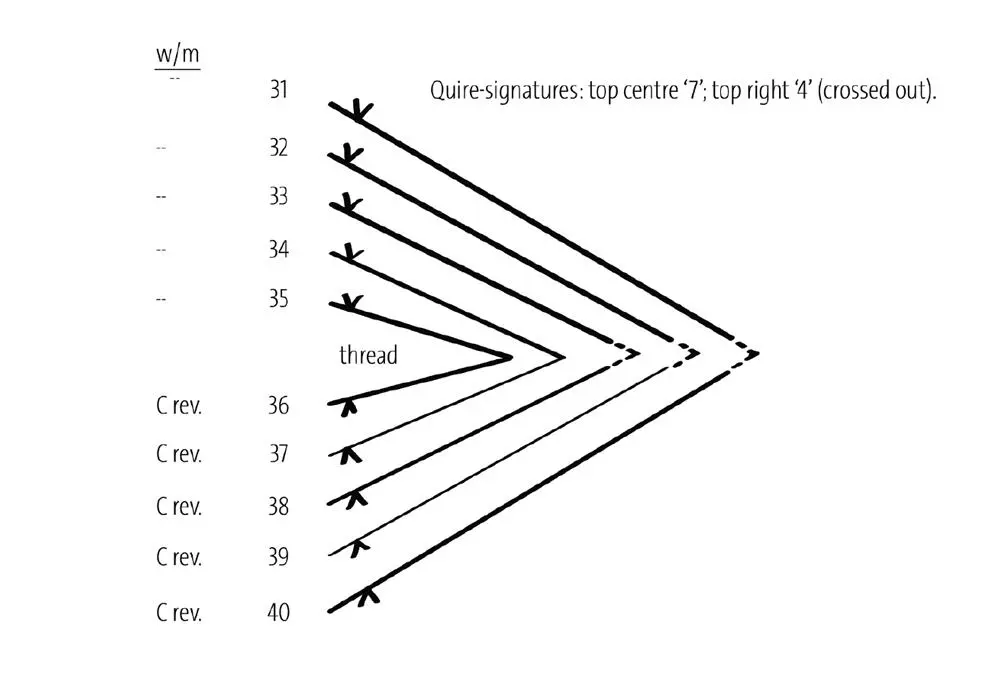

Chart 9. Quire IV

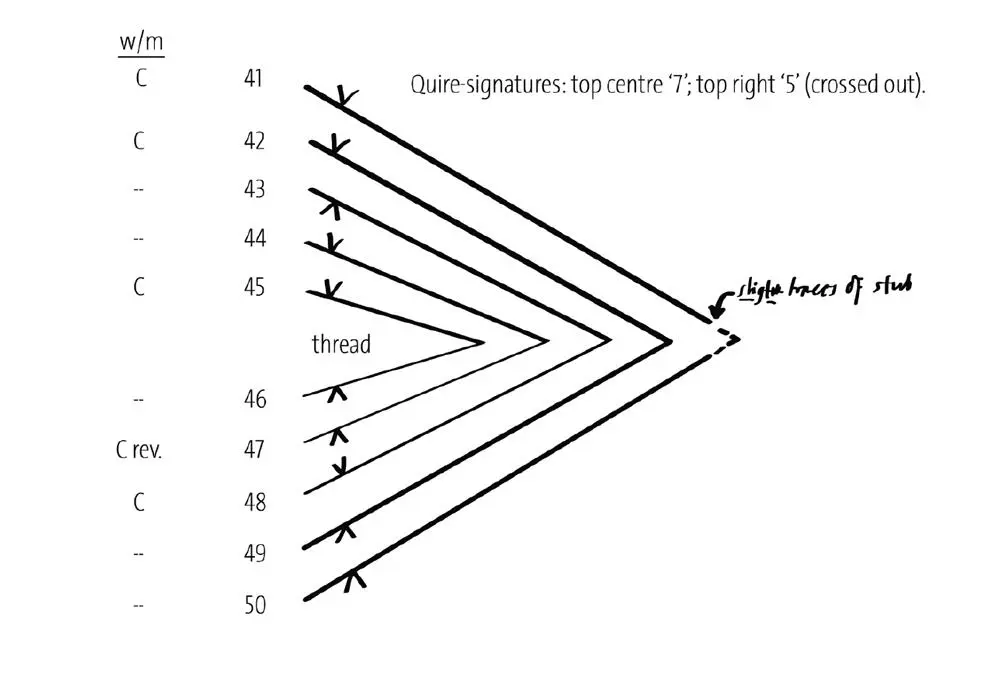

Chart 10. Quire V

Note on Quire V: The sequence of “mold” / “felt” sides of the paper is broken by the bifolium 43/48, where the two leaves are folded in reverse of the normal folding. However, since there is no sign of textual disturbance between folios 42v and 43r, 43v and 44r, 47v and 48r, and 48v and 49r, this reversal presumably happened accidentally when the quire of blank paper was formed before use.

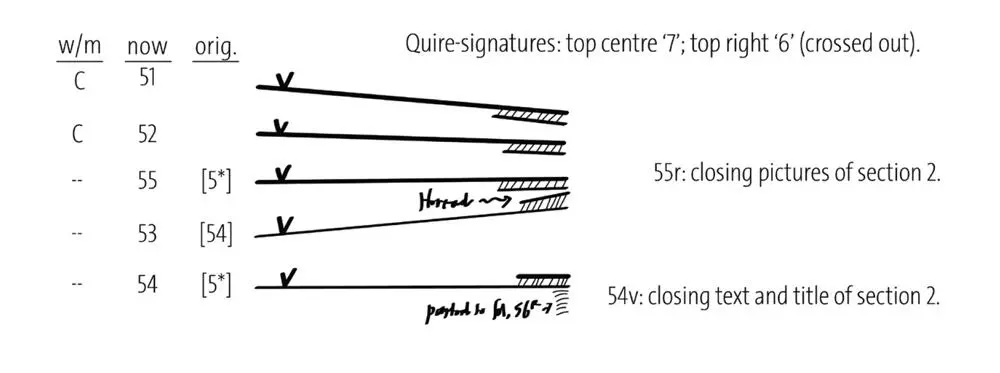

Quire VI

Apart from the edge repairs, this quire was left undisturbed during the repairs of 1986. Every leaf is lined at the gutter with a stub of paper similar to that used for the stubs (a), (c), and (d) in the front endleaves and Quire I, dating perhaps from the time of the seventeenth-century rebinding. The stubs here are all still firmly pasted down, and it is impossible to tell how those attached to folios 51, 52, and 54 connect and fit into the sewing structure.

Folio 55 has long been misplaced between folios 52 and 53 (Cooper Clark notes the disturbance, vol. I p. 85 n. 1, but artificially restores folio 55 to its correct position in his facsimile of 1938, vol. III; the same policy was followed in the 1992 facsimile). Folios 55 and 53 are artificially joined by a fold of what is thought to be the seventeenth-century repairing paper to form the central bifolium of the quire made up with a thread at the gutter.

In the seventeenth-century ink foliation on the rectos of folios 55, 53, and 54, each second digit has been altered. When viewed under the video spectral comparator, it is clear that the present “53” has been altered from “54,” but the first readings of the other two numbers are not clear. As noted above, under “Foliation,” the versos in this area of the manuscript (as sometimes elsewhere) are numbered with the folio number of the facing page, presumably to show that the opening was to be read as a unit with text-facing pictures. The verso foliations here are all entered correctly for the textual content, with “53” (on 52v), nothing (55v), “54” (53v) and “55” (54v). All the folio numbers, both recto (original and corrections) and verso, seem to be by the same seventeenth-century hand. The foliation evidence is difficult to evaluate, but the alterations at least confirm some disturbance in the order already present at the time of the seventeenth-century foliation.

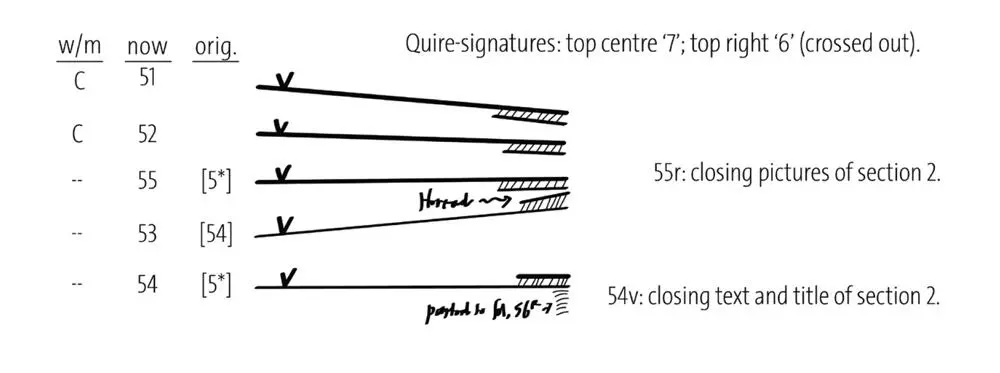

Chart 11. Quire VI, visible evidence

The above sequence (unlike that of chart 12) in fact fits the order suggested by the original foliation, as stated above in square brackets. In theory, foliation in this order might have taken place either before or after the disordering of the leaves. However, the most natural explanation would be that the foliator originally numbered the leaves on the rectos as he found them (perhaps already disordered). Then, after realizing the disorder, he corrected the numbers on the three rectos and added the correct equivalents on the relevant versos as well, though the misplaced folio 55 itself was left between 52 and 53 where it still remains.

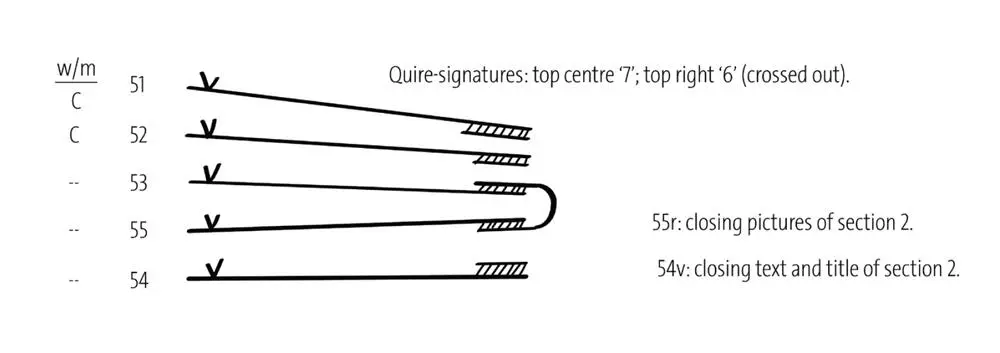

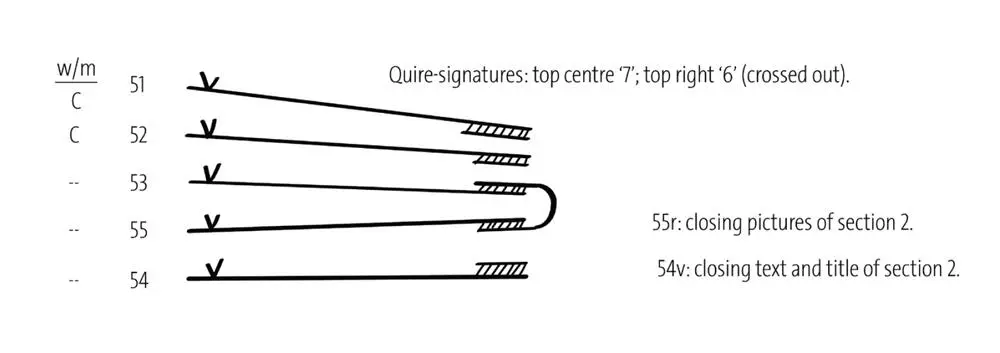

Quire VI, hypothetical reconstruction of Purcha’s order (1625 or before)

Chart 12. Quire VI [cont.]

The sequence of woodcuts of the Codex Mendoza in Purchas his Pilgrimes, Part 3 (London 1625, Bodleian shelfmark Lister E 55), pp. 1100-1101, shows pictures derived incompletely from these pages in the following order: (p. 1100) Codex Mendoza folios 52r, 53r, and (p. 1101) folios 55r and 54r. These woodcuts are the basis of the reconstruction in the chart below. The text, in English translation, fits the pictures, an order which could not have been achieved without some silent editorial reordering.

Unfortunately, the chronological relationships of Purchas’s edition, the strips of repairing paper, the seventeenth-century ink foliation, and the present seventeenth -century binding are not clear. Chart 12 may put too much weight on Purchas’s order, which takes only selected elements from each picture; nevertheless, all his other woodcuts are in the correct order. His evidence seems at least sufficient to confirm that the order of Quire VI was already disturbed by the time the materials for the 1625 edition were prepared (1625 at the latest). If chart 12 genuinely reflects the physical order of the leaves in Purchas’s time, it should be sufficient to date both the seventeenth-century binding and the foliation later than that time.

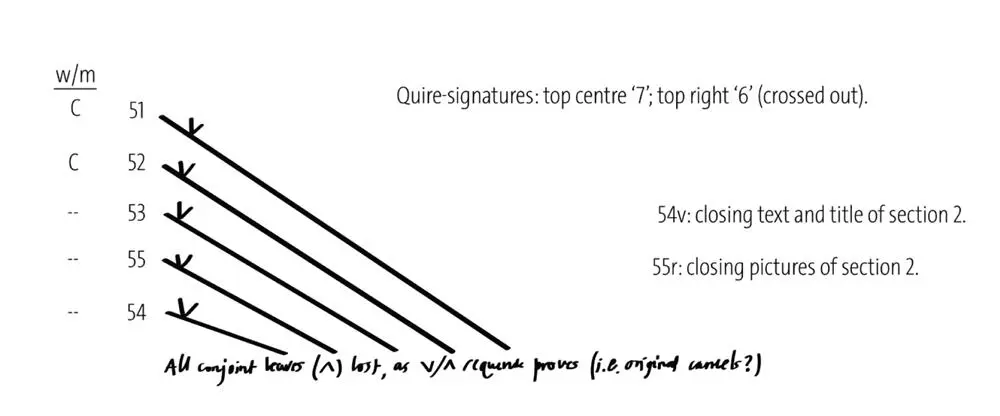

Since (apart from any artificial rejoinings) all five surviving leaves of the quire are singletons which lost their conjoint leaves long ago, their order when loose may not have been obvious. The positions of folios 55 and 54 might originally have been reversed by someone who did not realize that each page of text was to be read with its facing pictures; for example, the presence of the closing title of the second section at the end of the text on folio 54v, rather than after its pictures on folio 55r might have been enough to cause the reversal of the two leaves.

Subsequently, if by Purchas’s time folios 55 and 53 were already artificially joined into a bifolium at the center of a quire, their further reversal would only have been a small step, pushing folio 55 one further step back to its present position, as in chart 11.

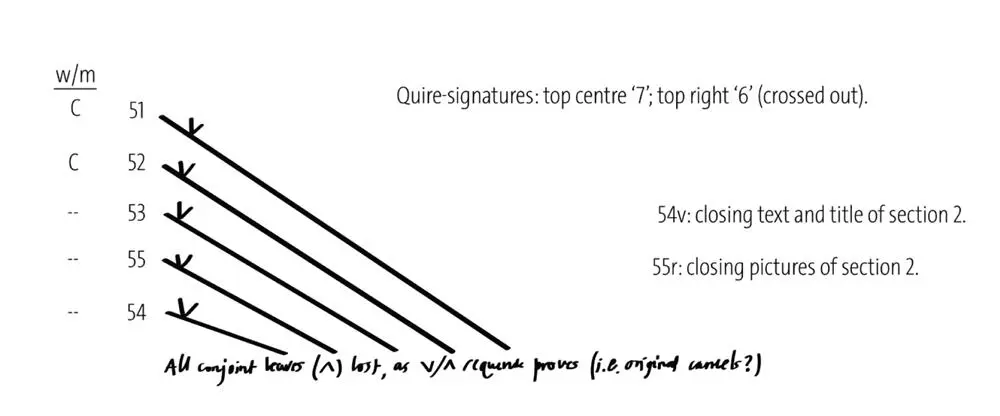

Original structure of Quire VI: hypothetical reconstruction

Chart 13. Quire VII

The change from Section 2 to Section 3 of the Codex Mendoza’s text coincides with the change from Quire VI to Quire VII (apparently deliberately created by the original elimination of the last five leaves of VI after folio 55) and with a change from “Pilgrim” to “Cross” paper. The structure of Quire VII could be accepted as quite regular were it not for traces of evidence between folios 64-5: escaped thread at the top and fragments of stub lower down the gutter. The appearance of one (though not both) of the standard quire signatures on folio 66 implies that folio 65 still belongs to Quire VII. At least two reconstructions are possible, which are detailed in the following sections.

Читать дальше