However, it should be noted that even this series of charts offers probably only an over-simplified account of the complex history of these leaves over four and a half centuries. The intense interest which they have always attracted must have made them ever vulnerable to overhandling and, hence, to frequent running repairs over the years.

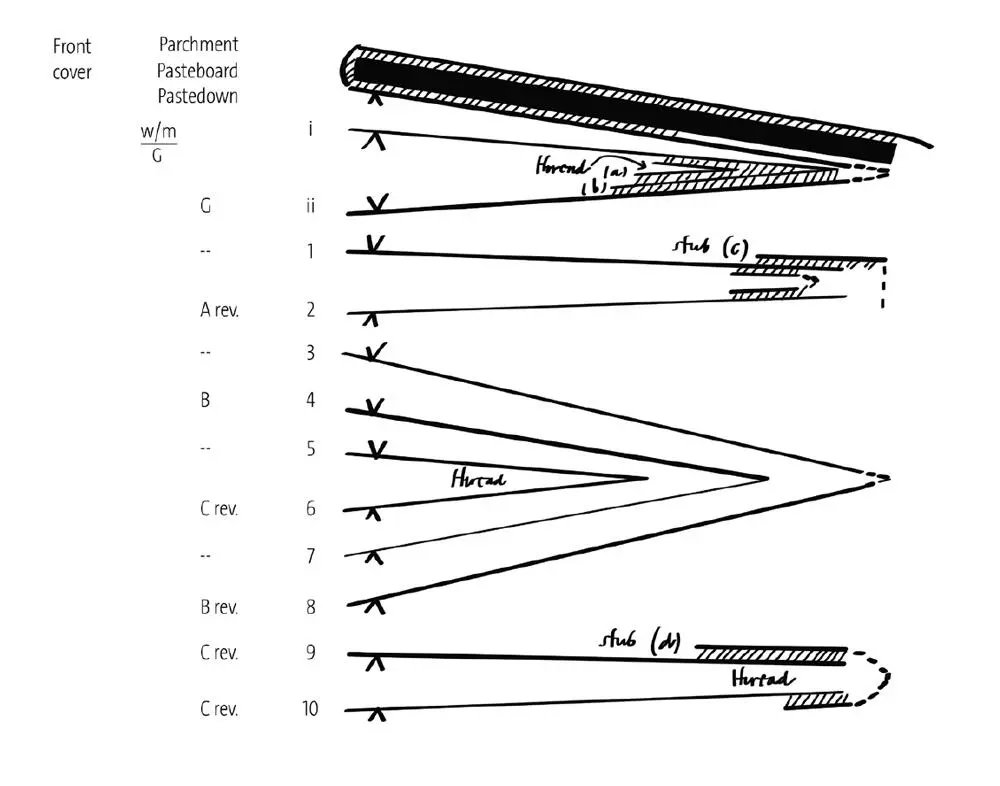

Front endpapers and Quire I:

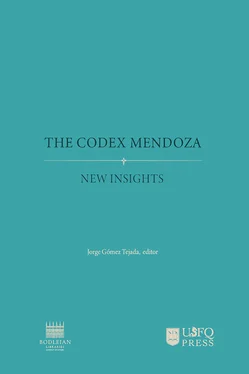

Changes made in 1986

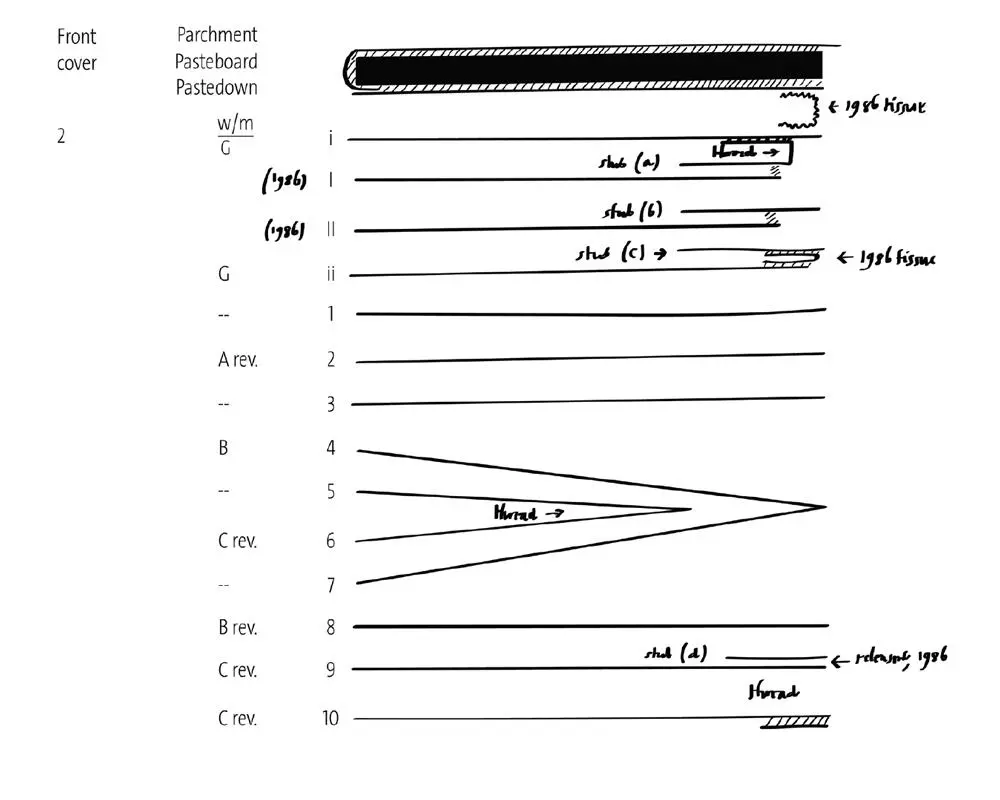

1.Folio i was released from the shoulder of the front pastedown to which it had been pasted.

2.Because of the build-up of paper and paste,1 the larger stubs (see charts below) were felt to be forming ridges and consequent weakening of the leaves against which they were pasted. They were released as follows:

–Stub (a) verso was released from stub (b) recto.

–Stub (b) verso was released from folio ii recto (stub [b] remains thickened with paste deposits on either side).

–Stub (c) verso was released from folio 1 recto.

–Stub (d) verso was released from folio 9 recto.

–Four strips of old repair paper at top and bottom of folios 1v and 2r (matching and presumably once conjoint to provide additional support for these leaves) were removed and discarded (these strips are visible in the Cooper Clark facsimile of 1938 and in the 1985 transparencies which were used for the facsimile of 1992).

3.Stub (c) was moved back one leaf from its position before folio 1 to a new position before folio ii, to prevent damage to folio 1 from its stiffened edge.

4.To prevent further pleating, two new flyleaves were added between folios i and ii:

Folio i was added between stub (a) and stub (b).

Folio ii was added between stub (b) and the relocated stub (c).

5.New repairing tissue had to be added across several gutters, e.g. between the front pastedown and folio i. These new joints do not imply that the adjoining leaves thus connected by the new tissue were necessarily originally conjoint.

Collation charts in reverse chronological order

Chart 1. State after the repairs of 1986: visible evidence only.

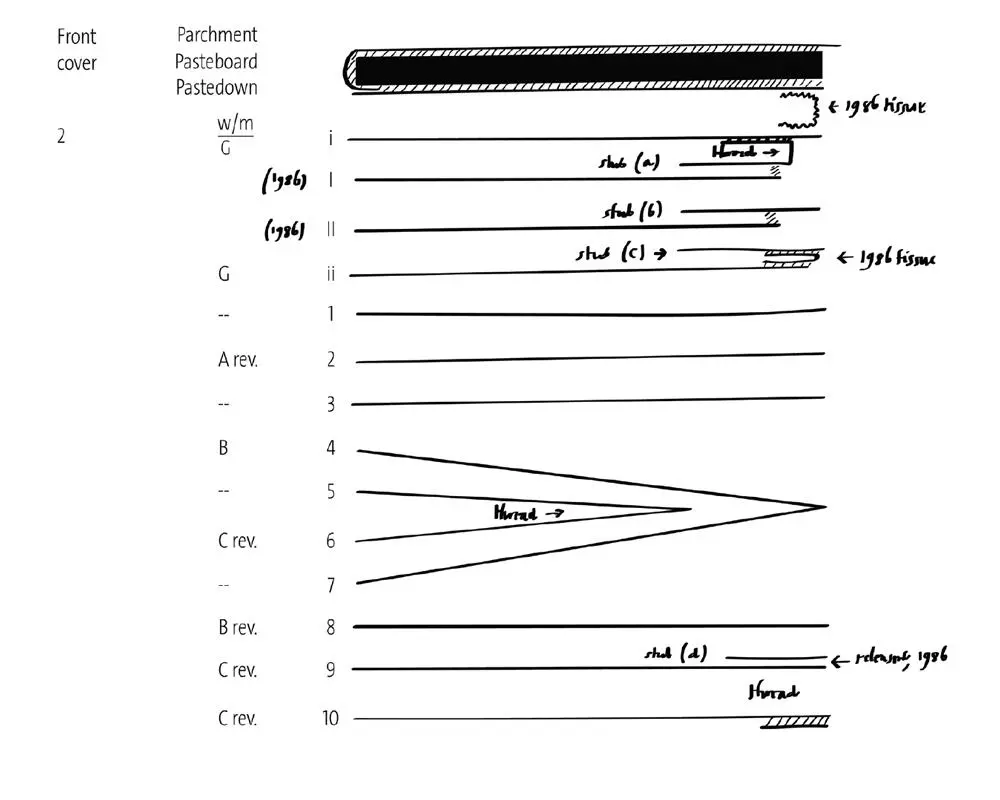

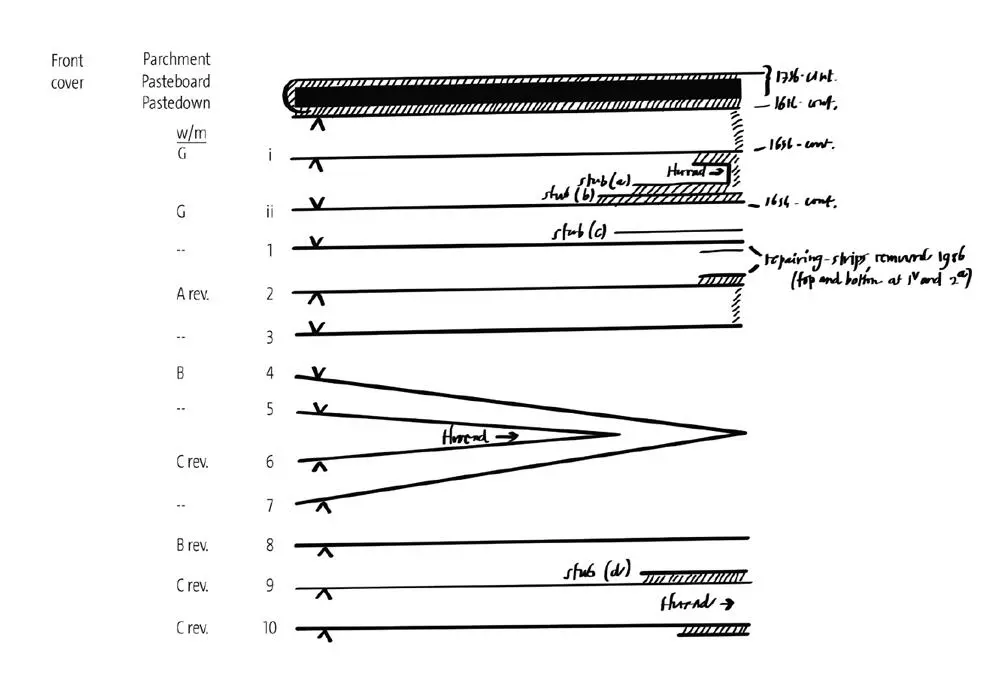

Chart 2. State before the repairs of 1986: visible evidence only

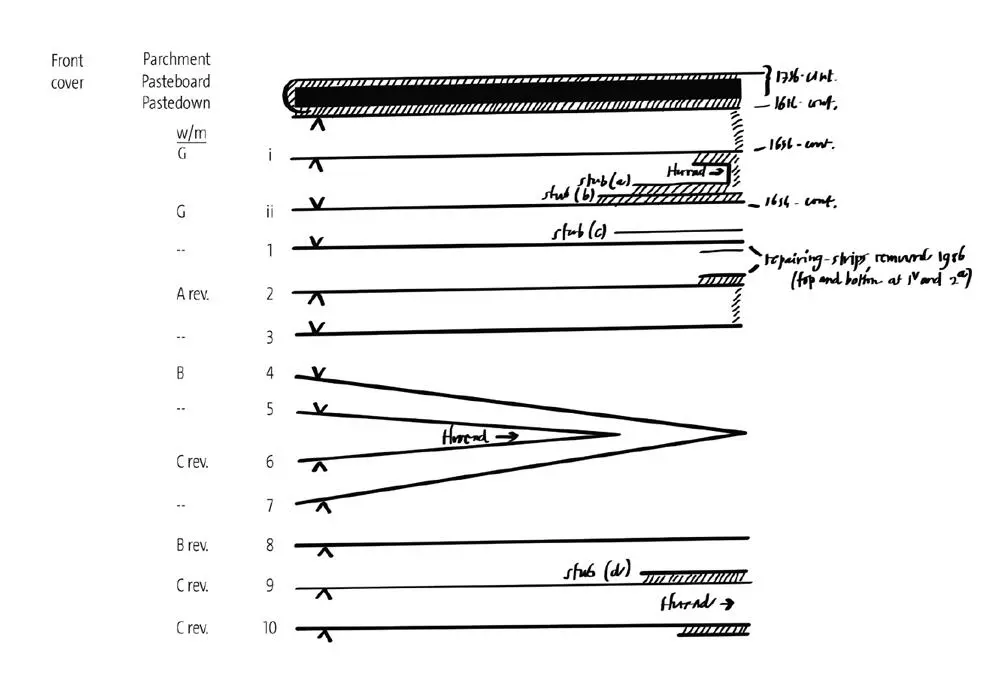

Chart 3. State before the repairs of 1986: hypothetical reconstruction (i.e. essentially as left by the seventeenth-century binder)

Notes on the stubs

1.Stub (a) and its mate (still firmly pasted to folio i verso), stub (c), and stub (d) and its mate (still pasted to folio 10v) are all of similar or perhaps the same laid paper. It seems slightly thicker than the papers of the main manuscript or of folios i-ii. Stubs (a) and (c) do not share the holes apparent at the gutters of folio i, stub (b), and folio ii (see below), and therefore were presumably added later. They may date from the time of the seventeenth-century rebinding.

2.There is no corresponding stub to provide a clue as to how stub (c) fitted into the structure. Its function could have been to help reinforce the join between folios 1 and 2 and/or to hold folios 1 and 2 in place.

3.The strip of paper which forms stub (a) and its mate is made up of two shorter strips pasted together end to end: the join occurs about two thirds of the way down. The chain-lines of both strips are horizontal in stub (a), but vertical in stubs (c) and (d).

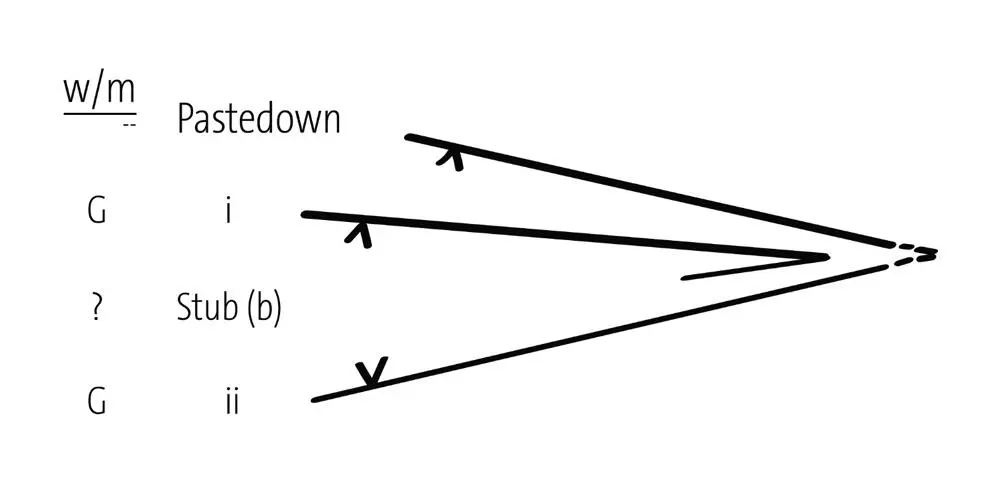

The front endleaves before the seventeenth-century rebinding: hypothetical reconstruction

The front pastedown has no visible watermark, but is probably of the same paper as folios i-ii and could be conjoint with folio ii. The prominent vertical pleats at the center of the pastedown exactly match those of folios i-ii, showing that, like them, it was once a free-standing flyleaf before it was used as the pastedown in the seventeenth-century binding. Although the texture of stub (b) is thickened and coarsened by deposits of paste on both sides, it still seems to be conjoined at the top with folio i. Since the pastedown carries the signature of André Thevet (d. 1592), these three leaves and stub must date, at the latest, from the manuscript’s period in France during the sixteenth century and before the manuscript’s voyage to London in 1587, as implied by the dated inscription on folio ii verso.

It has been argued by Frank Lestringant (1991, 38–39)2 that Thevet’s signature on the pastedown belongs not with his dated signatures of 1553 (folios 1r, 71v, with Latinized form “Thevetus”), but rather to a later group (front pastedown and folios 2r, 70v, French form of name, bolder script). This later group is undated, but on folio 2r it is accompanied by the title Cosmographe du Roi, which Thevet assumed, according to Lestringant, only from 1568/9. If this is correct (in spite of the slight suspicion that the signature and title on folio 2r might not be uniformly written), the signature on the present front pastedown might have been written after 1568. This does not provide a similar terminus ante quem non for the creation of that leaf itself, though a rebinding at some later stage of Thevet’s ownership would offer a motive for him to have rewritten his signature there. Despite all these uncertainties, it is tempting to very tentatively suggest that the earlier binding of the Codex Mendoza, as now represented only by the earlier endleaves, was made in the twenty years or so between 1568 and 1587. This would be entirely in line with the French watermarks of the 1570s which are indicated above as (non-exact) parallels with the watermarks of folios i-ii (Pattern G).

At their gutters, folios i, stub (b), and folio ii (but not stub [a] or stub [c]) have holes which do not seem to match the seventeenth-century sewing and which presumably predate it. This evidence is confusing, but these holes were perhaps caused both by earlier damage and by an earlier sewing-structure. Similar, though less severe damage appears in the equivalent blank leaf which follows the end of the Codex Mendoza (folio 72), which may therefore be presumed to belong with this group of early endpapers.

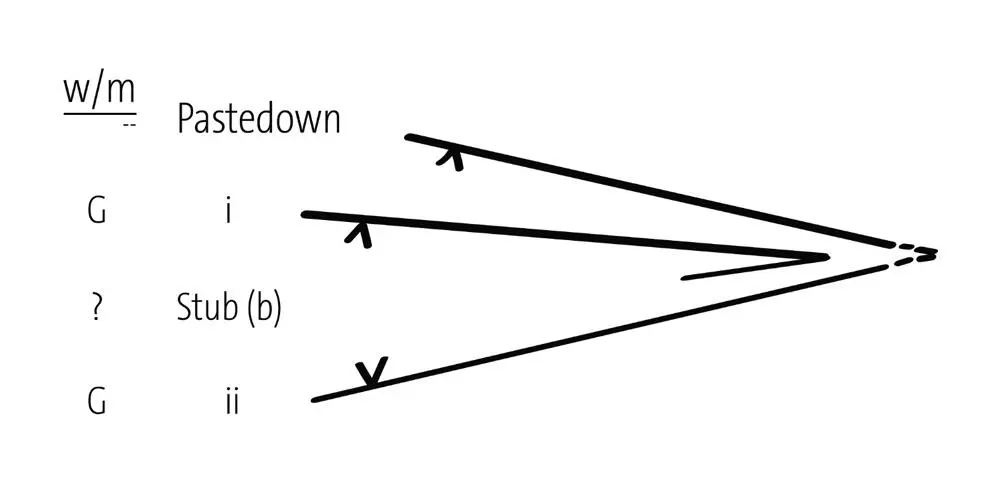

Chart 4. The front endleaves before the seventeenth-century rebinding: hypothetical reconstruction

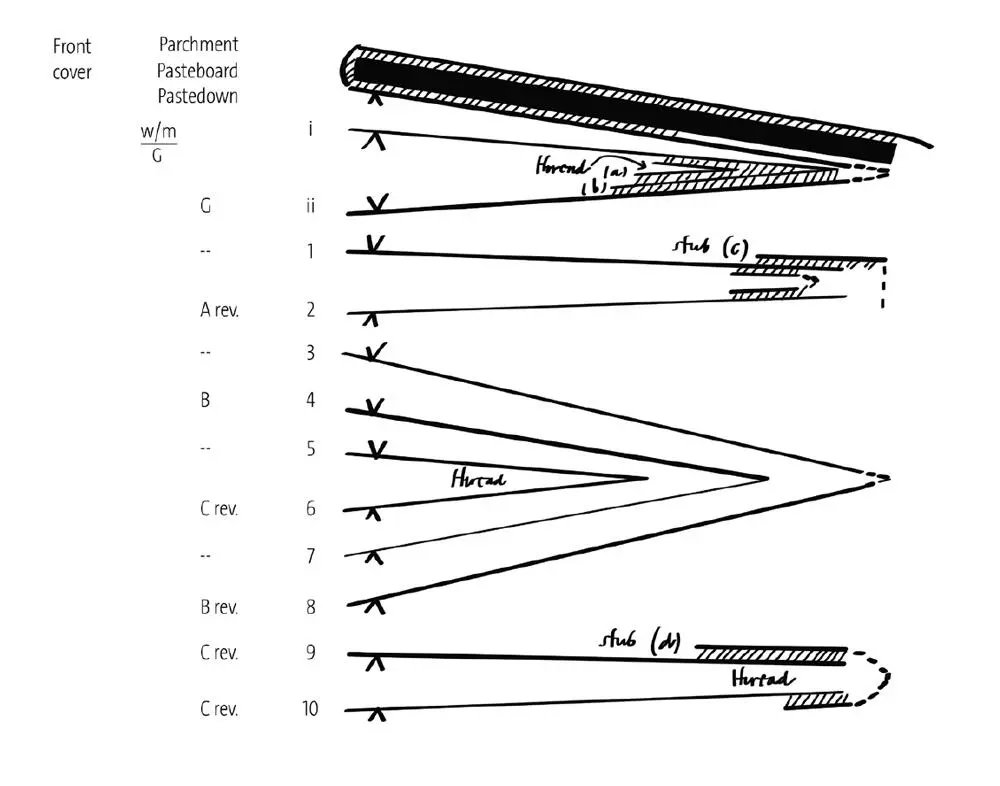

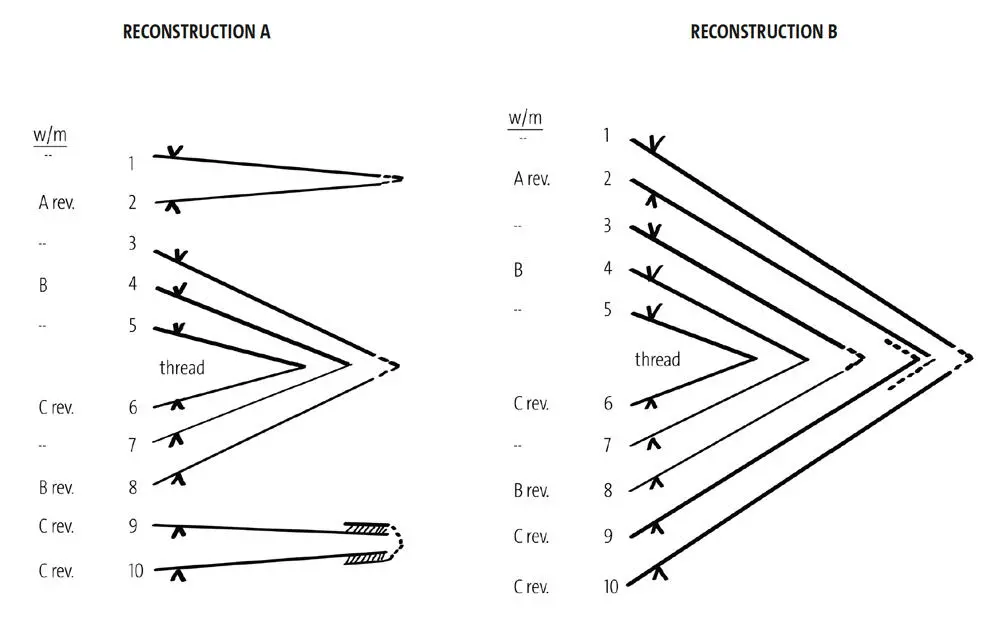

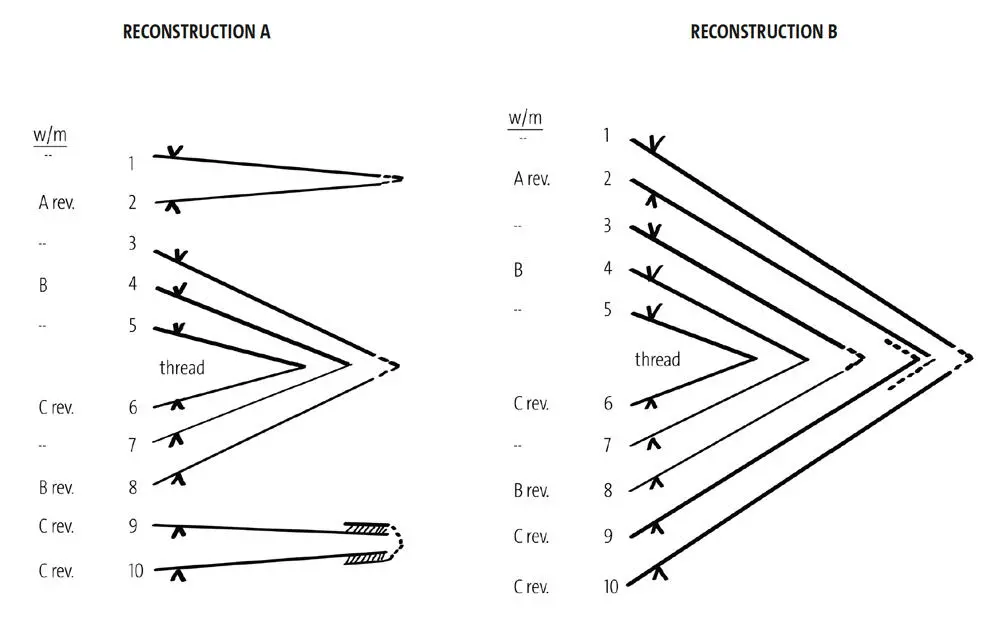

Original structure of Quire I: alternative reconstructions

Folio 9 can never have been conjoint either with folio 2 or with folio 10, since all three leaves carry watermarks and the directions of wire and felt sides do not fit. These types of evidence would allow folio 1 to have been conjoint either with folio 2 or with folio 10.

Charts 5-6. Original structure of Quire I: alternative reconstructions

Conclusion

Reconstruction B is the more economical solution: it assumes that a late decision was made to remake the original second leaf with a leaf of “pilgrim” paper carrying a slightly different watermark. The present folio 2 with the frontispiece is the only leaf that breaks the regular pattern of mold/felt sides. This disturbance meant that special arrangements had to be made to keep folio 9 in place after the loss of its original mate.

Читать дальше