John O'Brien - Earth Materials

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John O'Brien - Earth Materials» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Earth Materials

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Earth Materials: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Earth Materials»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Earth Materials,

Earth Materials,

Earth Materials — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Earth Materials», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Carbon isotopes

Three isotopes of carbon occur naturally in Earth materials: carbon‐12 ( 12C), carbon‐13 ( 13C) and the radioactive carbon‐14 ( 14C), used in radiocarbon dating. Each carbon isotope contains six protons in its nucleus; the remaining mass results from the number of neutrons (six, seven or eight) in the nucleus. 12C constitutes >98.9% of the stable carbon on Earth, and 13C constitutes most of the other 1.1%.

When organisms synthesize organic molecules, they selectively utilize 12C in preference to 13C so that organic molecules have lower than average 13C/ 12C ratios. Enrichment of the organic material in 12C causes the 13C/ 12C in the water column to increase. Ordinarily, there is a rough balance between the selective removal of 12C from water during organic synthesis and its release back to the water column by bacterial decomposition, respiration, and other processes. Mixing processes produce a relatively constant 13C/ 12C ratio in the water column. However, during periods of stagnant circulation in the oceans or other water bodies, disoxic–anoxic conditions develop in the lower part of the water column and/or in bottom sediments. These conditions inhibit bacterial decomposition ( Chapters 11and 14) and lead to the accumulation of 12C‐rich organic sediments. These sediments have unusually low 13C/ 12C ratios. As they accumulate, the remaining water column, depleted in 12C, develops a higher ratio of 13C/ 12C. However, any process, such as the return of vigorous circulation and oxidizing conditions, that rapidly release the 12C‐rich carbon from organic sediments, is associated with a rapid decrease in 13C/ 12C. By carefully plotting changes in 13C/ 12C ratios over time, paleo‐oceanographers have been able to document both local and global changes in oceanic circulation. In addition, because different organisms selectively incorporate different ratios of 12C to 13C, the evolution of new groups of organisms and/or the extinction of old groups of organisms can sometimes be tracked by rapid changes in the 13C/ 12C ratios of carbonate shells in marine sediments or organic materials in terrestrial soils.

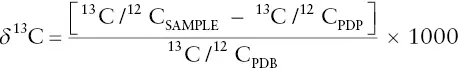

13C/ 12C ratios are generally expressed with respect to a standard in terms of δ 13C. The standard once again is the 13C/ 12C ratio of the Pee Dee Belemnite, or PDB. δ 13C is usually expressed in parts per thousand (mils) and calculated from:

Box 3.1illustrates an excellent example of how oxygen and carbon isotope ratios can be used to document Earth history, in this case a period of sudden global warming that occurred 55 million years ago.

3.3.2 Radioactive isotopes

Radioactive isotopespossess unstable nuclei whose nuclear configurations tend to be spontaneously transformed by radioactive decay. Radioactive decay occurs when the nucleus of an unstable parent isotopeis transformed into that of a daughter isotope. Daughter isotopes have different atomic numbers and/or different atomic mass numbers from their parent isotopes. Three major radioactive decay processes ( Figure 3.12) have been recognized: alpha (α) decay, beta (β) decay, and electron capture.

Alpha decayinvolves the ejection of an alpha (α) particle plus gamma (γ) rays and heat from the nucleus. An alpha particleconsists of two protons and two neutrons, which is the composition of a helium ( 4He) nucleus. The ejection of an alpha particle from the nucleus of a radioactive element reduces the atomic number of the element by two (2p +) while reducing its atomic mass number by four (2p ++ 2n 0). The spontaneous decay of uranium‐238 ( 238U) into thorium‐234 ( 234Th) is but one of many examples of alpha decay.

Beta decayinvolves the ejection of a beta (β) particle plus heat from the nucleus. A beta particleis a high‐speed electron (e −). The ejection of a beta particle from the nucleus of a radioactive element converts a neutron into a proton (n 0− e −= p +) increasing the atomic number by one while leaving the atomic mass number essentially unchanged. The spontaneous decay of radioactive rubidium‐87 (Z = 37) into stable strontium‐87 (Z = 38) is one of many examples of beta decay.

Electron captureinvolves the addition of a high‐speed electron to the nucleus with the release of heat in the form of gamma rays. It can be visualized as the reverse of beta decay. The addition of an electron to the nucleus converts one of the protons into a neutron (p ++ e −= n 0). Electron capture decreases the atomic number by one while leaving the atomic mass number unchanged. The decay of radioactive potassium‐40 (Z = 19) into stable argon‐40 (Z = 18) is a useful example of electron capture. It occurs at a known rate, which allows the age of many potassium‐bearing minerals and rocks to be determined. Only about 9% of radioactive potassium decays into argon‐40; the remainder decays into calcium‐40 ( 40Ca) by beta emission.

The heat released by radioactive decay is called radiogenic heat. Radiogenic heat is a major source of the heat generated within Earth. It is an important driver of global tectonics and many of the rock‐producing processes discussed in this text, including magma generation and metamorphism.

The time required for one half of the radioactive isotope to be converted into a new isotope is called its half‐lifeand may range from seconds to billions of years. Radioactive decay processes continue until a stable nuclear configuration is achieved and a stable isotope is formed. The radioactive decay of a parent isotope into a stable daughter isotope may involve a sequence of decay events. Table 3.2illustrates the 14‐step process required to convert radioactive uranium‐238 ( 238U) into the stable daughter isotope lead‐206 ( 206Pb). All of the intervening isotopes are unstable, so that the radioactive decay process continues. The first step, the conversion of 238U into thorium‐234 by alpha decay, is slow, with a half‐life of 4.47 billion years (4.47 Ga). Because many of the remaining steps are relatively rapid, the half‐life of the full decay, sequence is just over 4.47 Ga. As the rate at which 238U atoms are ultimately converted into 206Pb atoms is known, the ratio 238U/ 206Pb can be used to determine the crystallization ages for minerals, especially for those formed early in Earth's history, as explained below.

Those isotopes that decay rapidly, beginning with protactinium‐234 and radon‐222, produce large amounts of decay products in short amounts of time. Radioactive decay products, especially alpha particles, can produce notable damage to crystal structures and significant tissue damage in human populations ( Box 3.2). Radioactive isotopes also have significant applications in medicine, especially in cancer treatments. Radioactive decay provides a significant energy source through nuclear fission in reactors. Radioactive materials remain important global energy resources, even though the radioactive isotopes in spent fuel present long‐term hazards, expecially with respect to their disposal. As noted above, radioactive decay is also the primary heat engine within Earth and is partly responsible for driving plate tectonics and core–mantle convection. Without radioactive heat, Earth would be a very different kind of home.

Figure 3.12 Three types of radioactive decay: alpha decay, beta decay, and electron capture (gamma decay) and the changes in nuclear configuration that occur as the parent isotope decays into a daughter isotope.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Earth Materials»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Earth Materials» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Earth Materials» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.