1 ...8 9 10 12 13 14 ...25 Cough begins with closure of the vocal cords; this allows the forced contraction of the abdominal muscles and bracing by the intercostal muscles to generate a large positive pressure within the thorax. Sudden opening of the vocal cords then results in a forceful expiratory blast. The expiratory flow rate produced is much greater than that during voluntary forced expiration; the resultant shearing forces are particularly effective at removing secretions or inhaled solid material. When the vocal cords cannot be opposed, cough is much less effective and its character is quite different (see discussion of bovine coughlater in this chapter).

Cough is a protective reflex provoked by physical or chemical stimulation of irritant receptors in the larynx, trachea or bronchial tree. It may be dry or associated with sputum production. The duration and nature of a cough should be assessed, and precipitating and relieving factors should be explored. It is important to examine any sputumproduced, noting whether it is mucoid, purulent or bloodstained, for example. Cough occurring on exercise or disturbing sleep at night is a feature of asthma. A transient cough productive of purulent sputum is very common in respiratory tract infections. A weak, ineffective cough that fails to clear secretions from the airways is a feature of bulbar palsy or expiratory muscle weakness, and predisposes the patient to aspiration pneumonia.

Cough is often triggered by the accumulation of sputum in the respiratory tract. Chronic bronchitis is defined as cough productive of sputum on most days for at least 3 months of 2 consecutive years. Bronchiectasis is characterised by the production of copious amounts of purulent sputum. A chronic cough may also be caused by gastro‐oesophageal reflux (with or without aspiration), sinusitis with postnasal drip and, occasionally, drugs (e.g. ACE inhibitors). Violent coughing can generate sufficient force to produce a ‘ cough fracture’ of a rib or to impede venous return and cerebral perfusion, causing ‘ cough syncope’.

Haemoptysis is the coughing up of blood. It is a very important symptom that requires investigation. In particular, it may be the first clue to the presence of bronchial carcinoma. All patients with haemoptysis should have a chest X‐ray performed, and further investigations such as bronchoscopy, computed tomography (CT), sputum cytology and microbiology may be indicated, depending on the circumstances. The most important causes of haemoptysis are bronchial carcinoma, lung infections (pneumonia, bronchiectasis, tuberculosis), chronic bronchitis, pulmonary infarction, pulmonary vasculitis and pulmonary oedema (pink frothy sputum) ( Table 2.2). In some cases, no cause is found, and the origin of the blood may have been in the upper airway (e.g. nose [epistaxis], pharynx or gums).

Pain that is aggravated by inspiration or coughing is described as pleuritic pain, and the patient can often be seen to wince when breathing in, as the pain ‘catches’. Irritation of the pleura may result from inflammation (pleurisy), infection (pneumonia in adjacent lung), infarction of underlying lung (pulmonary embolism) or tumour (malignant pleural effusion). Chest wall pain resulting from injury to the intercostal muscles or fractured ribs, for example, is also aggravated by inspiration or coughing and is associated with tenderness at the point of injury. Whatever the cause of pleuritic pain, adequate analgesia is an essential component of treatment. If a patient is unable to take a deep breath or cough, pneumonia often follows.

Table 2.2 Major causes of haemoptysis

| Tumours Bronchial carcinomaLaryngeal carcinoma |

| Infections TuberculosisPneumoniaBronchiectasis |

| Infarction Pulmonary embolism (though haemoptysis is unusual) |

| Pulmonary oedema (sputum usually pink and frothy) Left ventricular failureMitral stenosis |

| Pulmonary vasculitis Goodpasture syndromegranulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) |

In addition to these major respiratory symptoms, it is important to consider other associated symptoms. For example, anorexiaand weight lossare features of malignancy or chronic lung infections (e.g. lung abscess). Pyrexiaand sweatingare features of acute (e.g. pneumonia) and chronic (e.g. tuberculosis) infections. Lethargy, malaise and confusion may be features of hypoxaemia. Headaches, particularly on awakening in the morning, may be a symptom of hypercapnia. Oedemamay indicate cor pulmonale. Snoringand daytime somnolencemay indicate obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Hoarsenessof the voice may indicate damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerve by a tumour.

Many respiratory diseases have their roots in previous childhood lung diseaseor in the patient’s environment, so that it is crucial to make specific enquiries concerning these points during history taking.

History

Past medical history

Did the patient suffer any major illness in childhood? Did the patient have frequent absences from school? Was the patient able to play games at school? Did any abnormalities declare themselves at a preemployment medical examination or on chest X‐ray? Has the patient ever been admitted to hospital with chest disease? A long history of childhood ‘bronchitis’ or ‘chestiness’ may in fact indicate asthma that was undiagnosed at the time. Severe whooping cough or measles in childhood may cause bronchiectasis. Tuberculosis acquired early in life may reactivate many years later.

Has the patient any systemic illness that may involve the lungs (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis)? Is the patient taking any medications that might affect the lungs (e.g. amiodarone or nitrofurantoin), which can cause interstitial lung disease, or β‐blockers (e.g. bisoprolol), which may provoke bronchospasm? What effect will the patient’s lung disease have on other illnesses (e.g. fitness for surgery?).

Is there any history of lung disease in the family? An increased prevalence of lung disease in a family may result from ‘shared genes’ (inherited traits such as cystic fibrosis, α 1‐antitrypsin deficiency or asthmatic tendency) or ‘shared environment’ (e.g. tuberculosis).

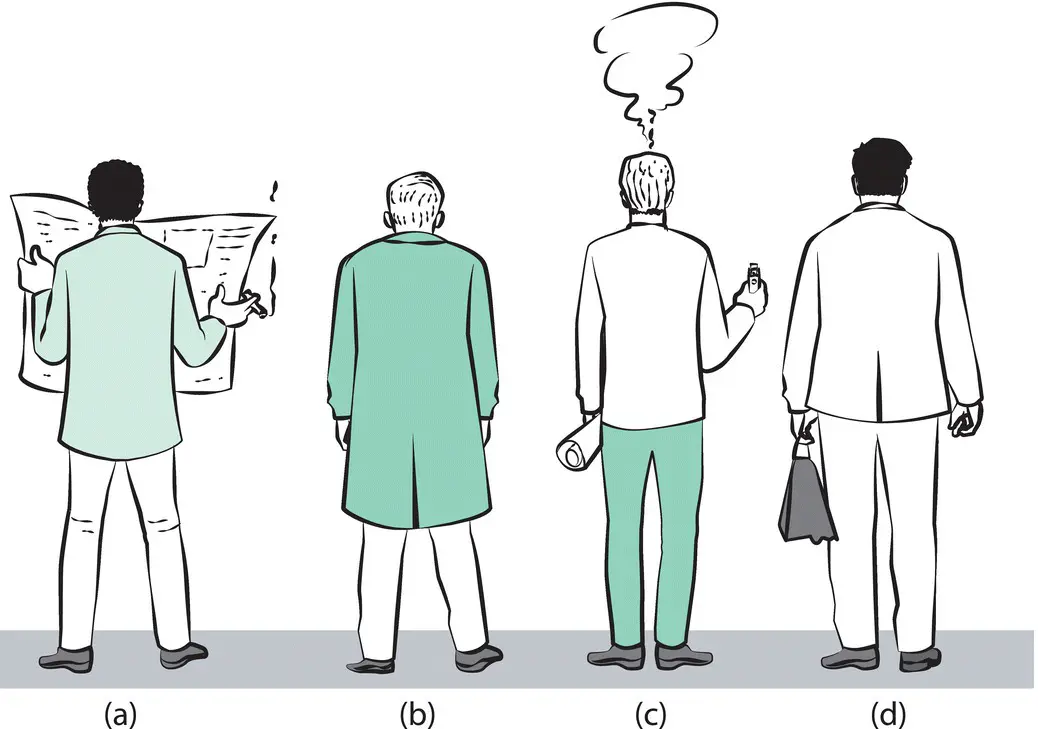

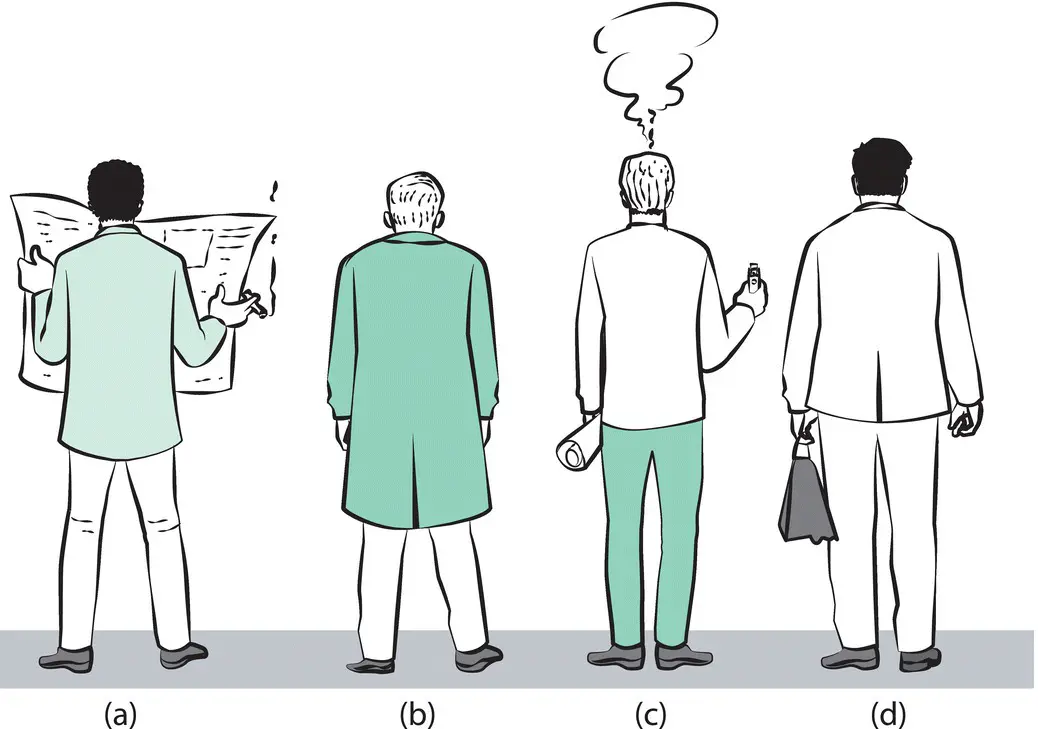

Figure 2.1 Which man has airway obstruction?

Answer to question in Fig. 2.1: (b) has airway obstruction – note the high position of the shoulders.

Does the patient smoke, or have they ever smoked? It is important to obtain a clear account of total smoking exposure over the years so as to assess the patient’s risk for diseases such as lung cancer or COPD. Pack‐year history should be calculated as follows: smoking one pack (20 cigarettes) per day for 1 year equates to 1 pack‐year. Does the patient keep any pets or participate in any sports (e.g. diving) or hobbies (e.g. pigeon racing) that might be important in assessing the lung disease?

What occupations has the patient had over the years, what tasks were performed and what materials were used? Do symptoms show a direct relationship to the work environment, as in the case of occupational asthma improving away from work and deteriorating on return to work? Has the patient been exposed to substances that might give rise to disease many years later, as in the case of mesothelioma arising from exposure to asbestos 20–40 years previously (see Chapter 14)?

Читать дальше