This however seems to be the case, for instance, in the KMK 3 National Standards for Teacher Education in Foreign Languages in Germany (KMK 2019), where only one reference is made – not to FL teachers’ professional classroom discourse competence but – to the level of L2 proficiency that pre-service teachers are expected to have reached by the end of phase 1: “University graduates have acquired in-depth linguistic knowledge [‘ Sprachwissen ’] and ‘native speaker-like’ L2 proficiency [‘‘ nativnahes ’ Sprachkönnen ’]; they are able to maintain this level and constantly refresh their foreign language competence.” (ibid.: 44; translation KT). Apparently, the underlying assumption here is that, from a linguistic point of view, native speaker-like (or C2+) proficiency in the target language is the determining factor for successful or effective teaching. The quoted passage above also suggests that EFL teachers’ preferably ‘native-like’ L2 language use within classroom settings is apparently no different from target language use in everyday real-world communication – or, if this distinction was indeed implied in the above quote, that teacher candidates would somehow automatically be able to (a) recognize these differences and (b) transform general L2 use into “pedagogically processed” language (Widdowson 2002: 77), i.e. the kind of language that is conducive to FL learning in classroom settings, the kind of language that activates learners, the kind of language “which has been pedagogically treated so that it is made less alien and more accessible to learners” (ibid.: 78).

The importance of this ‘professional dimension’ in teacher talk and teacher-navigated classroom discourse has, by and large, been neglected in teacher education programs and in conceptualizations of EFL teachers’ professional competence as well. More than fifteen years ago, Hallet (2006), for instance, emphasized the vital importance of teachers’ ‘professional discourse competence’, yet at the same time found that most competence models up until then did not even explicitly mention it. The author, therefore, concluded:

Actually, […] [discourse competence] deserves to receive more attention and ought to be given a central position in every competence model, given the fact that all processes of teaching and learning are language-based and […] therefore rely on continual communication and negotiation between all classroom participants. […] A precise description of this competence is requiredfor it to gain a professional dimension and to move beyond the notion of everyday communication.” (Hallet 2006: 127, 129, 130; translation and emphasis KT)

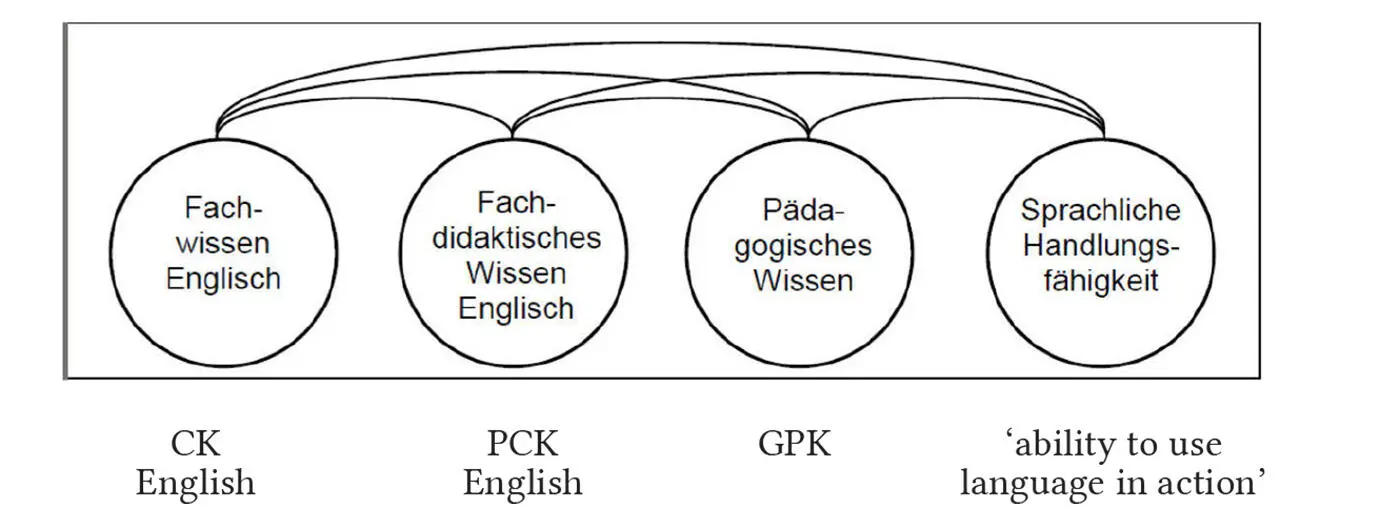

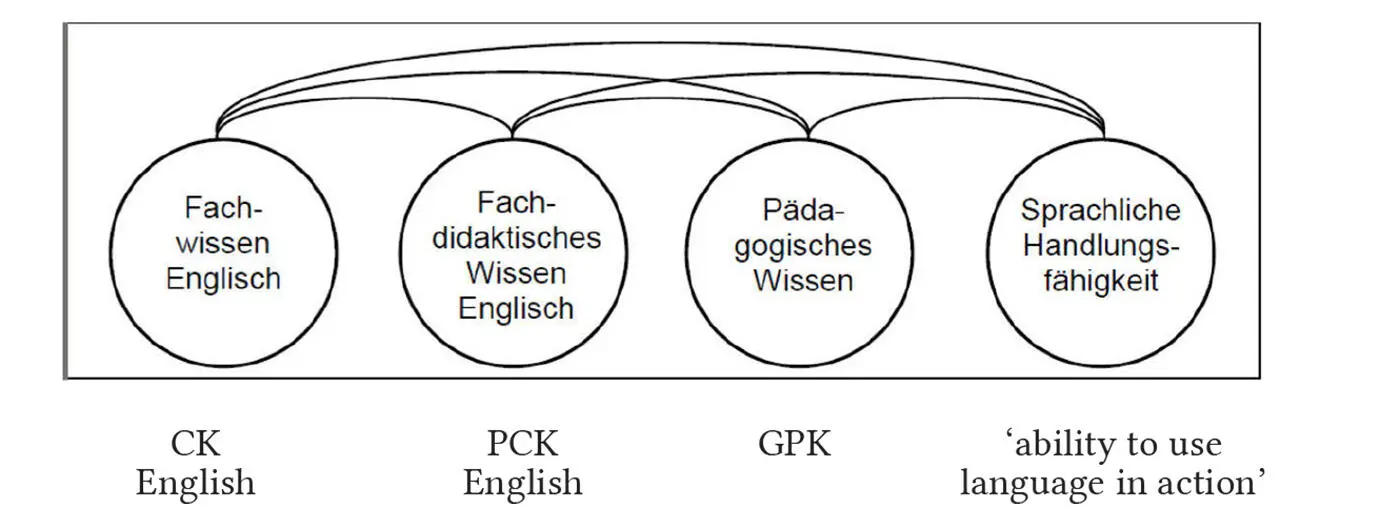

In foreign language teacher education and research in Germany, both of these calls have remained unanswered so far. While Shulman’s taxonomy (see Fig. 1) has been expanded to now also include a ‘linguistic component’ (“Sprachliche Handlungsfähigkeit”) in Roters et al.’s (2014) model of EFL teachers’ professional competence (see Fig. 2), the necessary distinction between teachers’ general foreign language communicative competence and a professional L2 classroom discourse competence is not made there.

Fig. 2:

Fig. 2:

EFL Teachers’ Professional Competence and Professional Knowledge (Roters et al. 2014, based on Shulman 1987)

Moreover, this form of visualization puts teachers’ “sprachliche Handlungsfähigkeit” on the same level with the different types of knowledge that (prospective) EFL teachers need to acquire. Whether or not this form of visual representation is appropriate is in fact a question worth tackling. Thus, the stance taken here is that (a) a distinction has to be made between ‘language competence’ and ‘classroom discourse competence’ (CDC) if a professional dimension is to be taken into account, and that (b) a conceptualization of CDC does not only call for a ‘precise definition’ of its components but also for a visual representation in which it is ‘given a more central position’ that reflects its key role in EFL teacher professionalism.

2.2 Existing Concepts and their Limitations – Conceptual Issues

Classroom communication and classroom interaction have been in the focus of researchers for a considerable amount of time (Schwab et al. 2017). Theoretical conceptualizations of these constructs and their respective competences have emerged from this. Existing concepts such as Johnson’s (1995) classroom communicative competence (CCC) or Walsh’s (e.g. 2011) classroom interactional competence (CCC) certainly offer valuable conceptual frameworks which allow for a deeper understanding of the processes involved in foreign language classroom communication and interaction as well as of the skills and competences required to participate in these. They do not, however, relate exclusively to FL teachers’ professional discourse competence (also see Thomson, “Introduction” in this volume).

Johnson’s notion of CCC, for instance, clearly denotes a language learner competence which enables them “to participate in and learn from their second language classroom experience” (1995: 6). Johnson defines CCC as “the knowledge and competencies that second language students need in order to participate in, learn from, and acquire a second language in the classroom” (ibid.: 160), and adds that CCC needs to be understood as “students’ knowledge of and competence in the structural, functional, social, and interactional norms that govern classroom communication” (ibid.: 160 and 168).

Shifting the focus from language learners to both language learners and teachers , Walsh’s CIC relates to “interactional strategies” (2011: 177) which enable “teacher[s] and learner[s] […] to use interaction as a tool for mediating and assisting learning” (ibid.: 158 and 165, also 2012: 1 and 5, 2013: 46 and 51, 2014: 4, Walsh/Li 2016: 495). Thus, these strategies, Walsh explains, are “open to both teachers and learners to enhance interaction and improve opportunities for learning” (Walsh 2012: 1). Defining CIC as a competence that both learners and teachers need to acquire, CIC, hence, is not exclusively conceptualized as a professional competence of language teachers. “CIC,” Walsh emphasizes, “focuses on the ways in which teachers’ and learners’ interactional decisions and subsequent actions enhance learning and learning opportunity.” (Walsh 2011: 165f.). Walsh, then, is primarily concerned with the question of “how teachers and learners display CIC” in classroom interaction (ibid.: 166).

Language learners having acquired CIC are, for instance, able to recognize a teacher’s pedagogical focus when using a particular type of question and to give relevant, timely, adequate and appropriate answers (ibid.: 174f.). Furthermore, learners displaying CIC are able “to manage turns, hold the floor and hand over […] turn[s] at a particular point in the interaction”, and they recognize and correctly interpret “key signals” in classroom discourse (ibid.: 174; for these examples and quotes also see Seedhouse/Walsh 2010: 144f.).

Language teachers , on the other hand, display CDC through ‘interactional strategies’ such as “us[ing] language which is both convergent to the pedagogical goal of the moment and which is appropriate to the learners” (Walsh 2012: 6, also Walsh 2014: 5). CIC is also demonstrated by teachers who manage to “creat[e] [interactional] space for learning” and are able to “shap[e] learner contributions” (ibid.). These clearly pedagogically motivated strategies certainly play an important role in a teacher’s classroom discourse repertoire.

Читать дальше

Fig. 2:

Fig. 2: