The term ‘classroom discourse’ […] refers to all forms of discourse that take place in the classroom. It encompasses the linguistic as well as the nonlinguistic elements of discourse. The former includes the language used by the teacher and the learners, as well as teacher-learner and learner-learner interactions. The latter includes paralinguistic gestures, prosody, and silence – all of which are integral parts of the discourse.

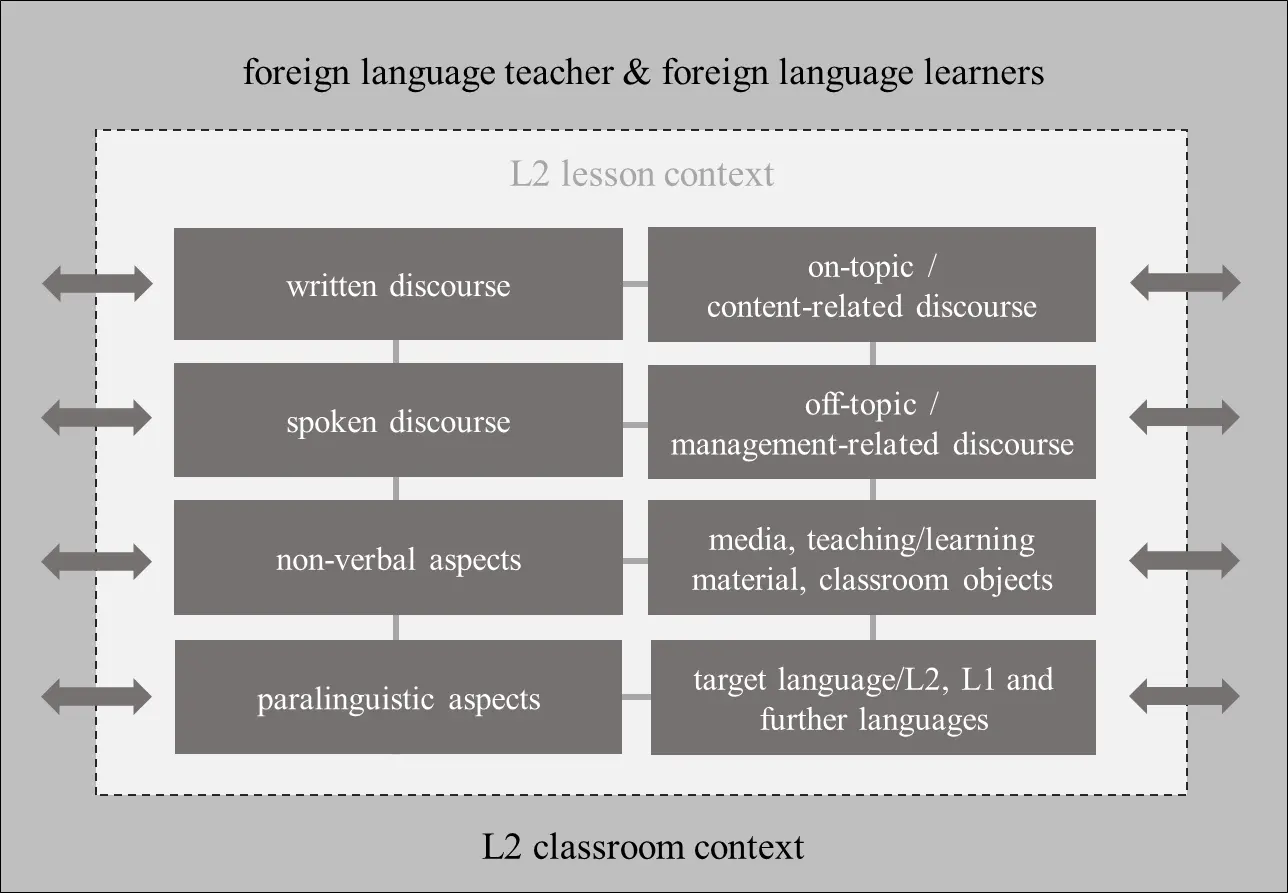

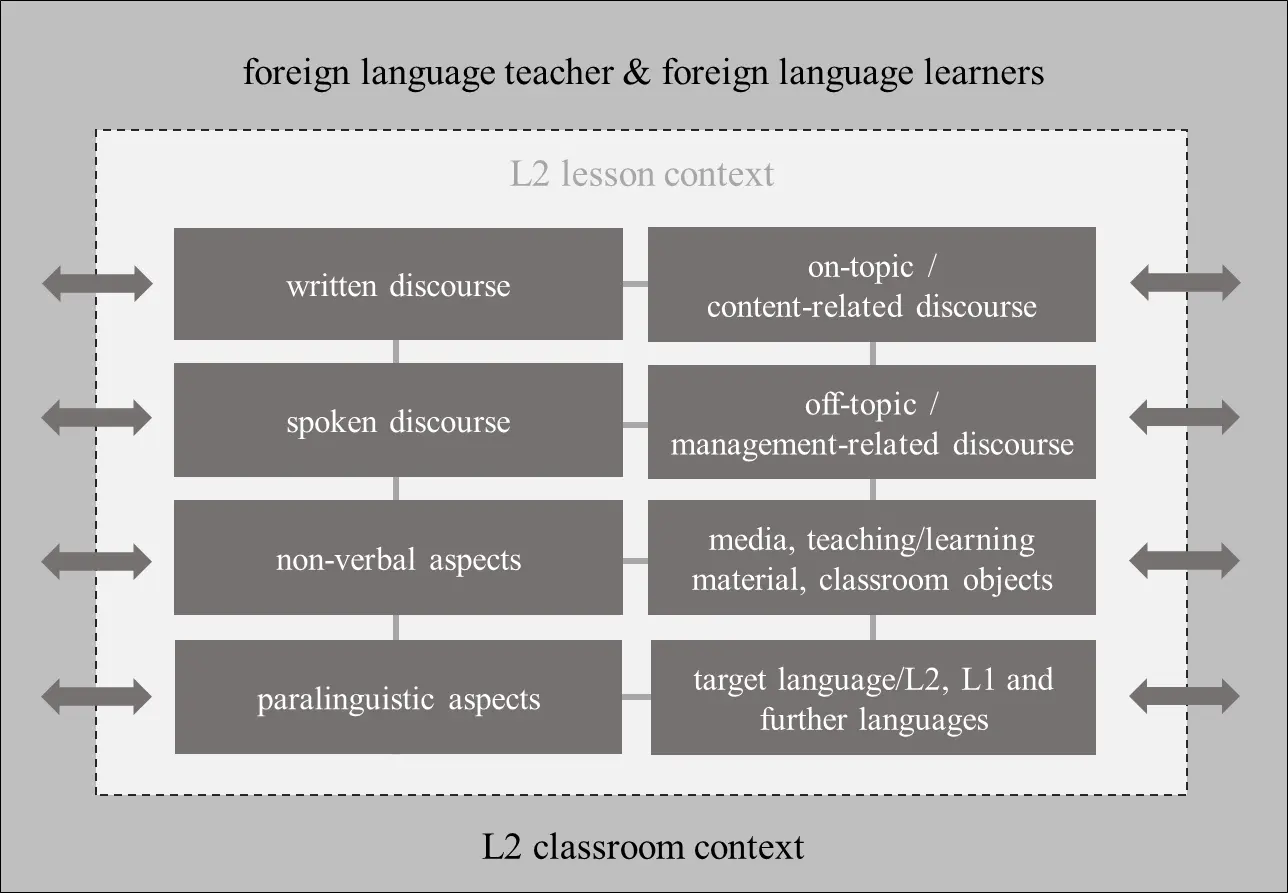

Another conceptualization of ‘classroom discourse’ (see Fig. 1) ties in with Tsui’s but expands it by taking further important aspects into consideration as well:

Fig. 1:

Fig. 1:

Classroom discourse in the context of foreign language education (Thomson 2020b: 7, adapted)

‘Classroom discourse’, as shown in Fig. 1, (#1) includes all interlocutors participating in the discourse processes. While in most cases this usually involves teachers and learners, it could also refer to invited guest speakers, co-teachers in school projects, prospective students etc. (#2) That said, ‘classroom discourse’ encompasses all communicative and interactional processes including monological formats (e.g. teacher talk in an extended input-phase, a student presentation) as well as dialogical formats with two or more interactants (e.g. between teacher—student and student—student). (#3) Furthermore, the notion of ‘classroom discourse’ is not restricted to the lesson context (i.e. the actual class time of usually 45 or 90 minutes) but transcends such temporal boundaries so as to acknowledge the fact that interaction and communication in the L2 may begin even before a lesson starts (e.g. greeting each other, T-S small talk, taking care of managerial issues etc.) and continue after a lesson has ended (e.g. extended teacher feedback to individual students, Q/A on issues discussed during the lesson etc.). As Fig. 1 indicates (see the dotted line and arrows), the lesson context is embedded in the classroom context and both are closely intertwined, i.e. any discourse-related aspect may permeate from one into the other context. That is to say: valuable opportunities for (authentic) language use and language learning can be created beyond the lesson bell if teachers are aware of the broader scope of L2 classroom discourse. (#4) Although ‘classroom discourse’ is often associated with the spoken/oral discourse, it does refer to the written discourse as well. Students’ note-taking, the texts written into their folders, a teacher’s feedback or comments written in the margin of test papers, ideas collected on the blackboard/whiteboard, hand-written notes secretly being passed among students etc. – all of these are forms, some overt/covert, some public/private, that shape and impact classroom discourse. (#5) As far as spoken classroom discourse is concerned, nonverbal and paralinguistic features have to be taken into consideration as well. In language teaching/learning contexts, this is far more than a footnote because, if used effectively, nonverbal elements (such as facial expressions, gestures, gaze, positioning and movements within the physical classroom space), posture and proximity can enhance comprehension, encourage students to participate and help to structure the discourse for language learners. Likewise, paralinguistic aspects (such as pace, pausing, silences, volume, pitch variation, prosody, intonation, articulation etc.) allow teachers to flexibly adjust their utterances to the individual needs and proficiency levels of their learners.

(#6) Classroom discourse, as defined here, comprises on-topic as well as off-topic interaction and communication. On-topic classroom discourse subsumes all forms of content-focused communication/interaction taking place on the main level of discourse (e.g. a class discussion about a literary text or a cultural phenomenon, students explaining structural regularities which they may have discovered in new grammatical forms). Off-topic communication/interaction relates to managerial and procedural issues dealt with on the level of classroom management (e.g. room management, seating arrangements, task instructions, classroom disruptions etc.). This distinction, however, does not imply that only on-topic discourse would facilitate language learning. Quite the contrary (see Thomson’s chapter on “L2 classroom management competence”).

(#7) In classroom discourse, communicative and interactional processes do not take place within a spatial vacuum but rather in a concrete teaching and learning environment with a multitude of materials/resources (e.g. worksheets, posters, coursebooks, dictionaries), media (e.g. blackboard, projector, CD player) and objects (e.g. pieces of classroom furniture). Explicit references to those entities are made frequently, especially in the managerial classroom discourse, and it is often through their integrated use in classroom work that learning and teaching processes develop and proceed. Teaching/learning materials and media in particular can take on an (inter-)active role in the discourse – Hallet (2006: 76) speaks of ‘didactic entities’ (“didaktisch[e] Instanz[en]”) – if they pre-select learning content, provide task instructions and explanations, structure students’ working process and the lesson as such.

(#8) The most important factor in classroom discourse is, of course, language itself. In foreign language education, L2 learning cannot be facilitated if teachers do not use the target language effectively, consistently and with pedagogical intention. Nor does L2 learning take place if language learners, for whatever reasons, do not communicate and interact in the foreign language. Thus, the preferred language to be used is the L2. In foreign language classrooms, though, there is always at least one more language that permeates, influences and shapes the discourse in various ways: the teacher’s and/or students’ L1. That is to say, ‘classroom discourse’ in language teaching/learning contexts does not only refer to the target language to be learned, but to any other language spoken by the teacher and individual students in a particular learner group (e.g. heritage languages, second or other foreign languages already acquired etc.). Hence, in multilingual and/or culturally diverse classrooms, additional languages (L3, L4 etc.) can serve as linguistic resources that teachers and learners can tap into. It is for this particular reason that the term ‘L2 classroom discourse’ finds its German equivalent in fremdsprachenunterrichtlicher Diskurs – rather than fremdsprachlicher Unterrichtsdiskurs , although both types exist and may overlap, of course. This distinction is a crucial one because it takes account of the language diversity that teachers and students may potentially encounter in foreign language classroom discourse, and it acknowledges the important role that especially the L1 may play in certain lesson contexts. Thus, it rejects the idea that L2 classroom discourse solely encompasses interaction and communication in the foreign language. From a teacher’s perspective, mastering all classroom discourse-related teacher tasks in ways that are conducive to student learning thus requires a high level of L2 classroom discourse competence (CDC). This term, then, has its equivalent in fremdsprachenunterrichtliche Diskurskompetenz – not fremdsprachliche Unterrichtsdiskurskompetenz.

4 Structure and Content: The Contributions in this Volume

This volume on classroom discourse competence (CDC) is divided into three parts and consists of a total of fifteen chapters. The contributing authors in this book approach CDC from different angles and discuss selected issues. What all of these contributions share, however, is their focus on English language teaching/learning and the question of how CDC and its related sub-competences can be promoted in the context of pre-service EFL teacher education at university level.

Читать дальше

Fig. 1:

Fig. 1: