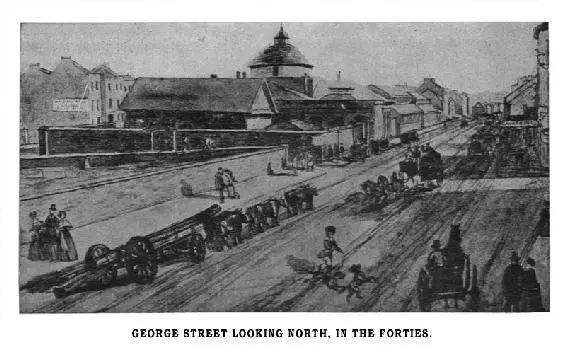

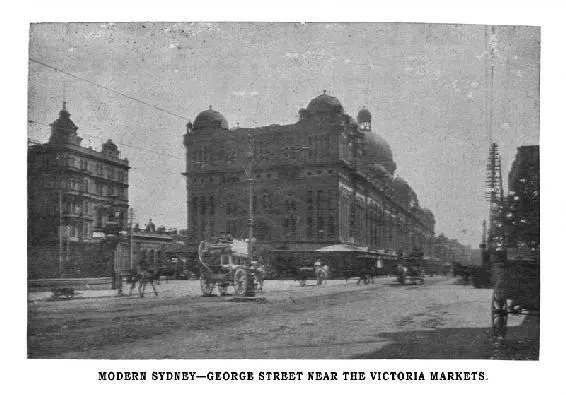

Although the readers of this book should be able to form for themselves, aided by the pictures, a fairly accurate idea of Sydney at the various ages of its growth already touched upon, yet, to give effect to these, something must be said of the men and women, our forbears, who had their being, and lived their lives under so much less happier auspices than do we the present day.

But contemporary historians have not given us, in this respect, very much to go upon. Their time was too greatly taken up by chronicling political squabbles, and the gradual expansion of the colony outside the capital, to afford any leisure for more in a glimpse now and again into the social life of Sydney itself.

Says an early visitor, writing just about the advent of Governor Brisbane:

“Society is upon a much better footing throughout the colony in general than might naturally be imagined, considering the ingredients of which it is composed. In Sydney the civil and military officers with their families, form a circle at once select and extended, without including the highly numerous respectable families of merchants and settlers who reside there. Unfortunately, however, the town is not free from those divisions which are so prevalent in all small communities. Scandal appears to be the favourite amusement to which idlers resort to kill time and prevent ennui; and, consequently, the same families are eternally changing from friendship to hostility, and from hostility back again to friendship.”

These conditions, it may be remarked, will still hold good at present of many other towns, besides Sydney some eighty years ago.

Continues our author: “Of the number of respectable persons some estimate may be formed if we refer to the parties which are given on particular days at the Government House.” Even now many people gauge respectability by much the same test. And notice that word “respectable.” It occurs throughout the old chronicles, and is pregnant with meaning. To be respectable in those days was apparently to be “pure merino,” with no taint even of the emancipist, let alone of the actual convict, about you. And that such spotless ones among the flock were very far from being numerous is shown by the fact that at one of these Government House festivals, in 1822, there were about 160 “respectable” ladies and gentlemen.

Writing a year or two later, the author, already quoted above, remarks rather significantly: “There are at present no public amusements in this colony. Many years since there was a theatre, and more latterly annual races. But it was found that the society was not sufficiently mature for such establishments.” Reading here between the lines, one seems to have unpleasant visions of what our early “general public” was like. Later on, as we shall see, they matured, and, presumably, improved.

From all that can be gathered, and that is but little, our folk of the early years led lives, that, if busy, were none the less monotonous, void of social amusements, except, perhaps, at long intervals, a supper and ball at Government House, or some public celebration like that of the Anniversary Dinner. Of their home life, there has been no word-painter, and of it we know little or nothing.

This function, the Anniversary Dinner, merits rather more than passing notice. The first one on record seems to have been on January 26, 1817, and was held by Isaac Nichols, Postmaster of Sydney, at his house in Lower George-street, at the head of the Cove, to celebrate the 29th anniversary of the foundation of the colony. There are forty select, and presumably thoroughly “respectable” guests, who sit down to table at five in the afternoon, and retire at ten that night.—There are loyal toasts proposed after the cloth is removed; and the “Muse of Mr. Jenkins,” who is the chairman, has composed a song, which is sung to the tune of “Rule Britannia.” A verse or so will suffice to give the reader an idea of this, undoubtedly the first Australian patriotic song:—

When first Australia rose to fame,

And Seamen brave explored her shore

Neptune with joy beheld their aim.

And thus express’d the wish he bore.

Chorus—

Rise, Australia! - with peace and plenty crown’d

Thy name shall one day be renown’d.

Then Commerce, too, shall on thee smile,

Adventurous barks thy ports shall crowd;

While pleas’d, well pleas’d, the Parent Isle

Shall of her distant sons be proud.

Chorus—

Rise, Australia! with peace and plenty crown’d,

Thy name shall one day be renown’d.

And who shall say that “Mr. Jenkins” did not make a very fine forecast indeed, and one fulfilled to the very letter?

Next year the celebration became official, taking place at Government House, while in the evening Mrs. Macquarie gave a ball. Mr. Howe, the editor of the “Gazette” was graciously allowed the privilege of a look round during the evening—not being “respectable” that, of course, was as much as he could expect—and he appears to have been very much taken with a portrait of Admiral Phillip, which was suspended at one end of the room, encircled with wreaths and banners, and an inscription running:—“In commemoration of the thirtieth anniversary of the colony of New South Wales established by Arthur Phillip, whose virtues and talent entitle him to the grateful remembrance of this country, and to whose arduous exertions the present prosperous state of the colony may chiefly be ascribed.” Which goes to show that contemporary recognition of the first Australian pioneer was stronger than that of succeeding generations; and, indeed, until quite recently, in our own day. The artist was a Mr. Greenaway, the Colonial Architect; and it would be of interest to know if that old portrait is still in existence.

The thirty-second anniversary (1820) was celebrated by a public dinner at Hankinson’s rooms, in George-street, which was attended by “sixty or seventy respectable persons.” But on this occasion there was no enthusiasm to speak of, owing to the fact of the guests being over-charged. The tickets for the dinner cost 40s—“without any kind of refined articles, such as jellies or blanc manges, and the elegance of a tip-top tavern table, such as could be had in London for a quarter of the money.”

Some of these good people had probably been glad enough, in the starvation years, of a feed of hominy, and now they are growling because mine host had not provided blanc manges and jellies! And, by the way, it is remarkable that now we find this function left chiefly to the emancipists, who, apparently, have been admitted to call themselves “respectable.” This was, of course, Macquarie’s doing; for only a month or two after landing he had shown very clearly where his sympathies lay by making a convict a magistrate. Certainly, the person in question had been transported for some petty offence at the age of 16. But the affair, nevertheless, gave a tremendous shock to the untainted members of the community.

In 1821. the thirty-third anniversary was perhaps the most successful of any so far. It took place at Gansdell’s Rooms, Hyde Park, when 101 emancipists sat down to a great spread. Dr. Redfern was president, Simeon Lord was vice-president, and there were eight stewards. It is particularly noted by the chronicler of the affair that both dinner and wines were excellent.

Читать дальше