And in this extraordinary fashion did Sydney get her first general hospital.

Surely never any charitable institution founded under such, to say the least of it, disreputable circumstances! Still though Macquarie’s contemporaries raged bitterly against him doubtless, out of the evil that attended its birth came eventually much good and comfort to the suffering. It served its purpose, even as does the beautiful building that now stands on the site of the “Rum Hospital” a portion of which, the southern wing, still remains with us in the shape of the Mint.

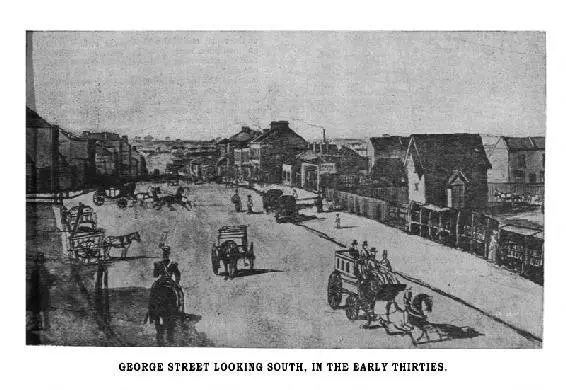

Chapter IV – Early Social Life

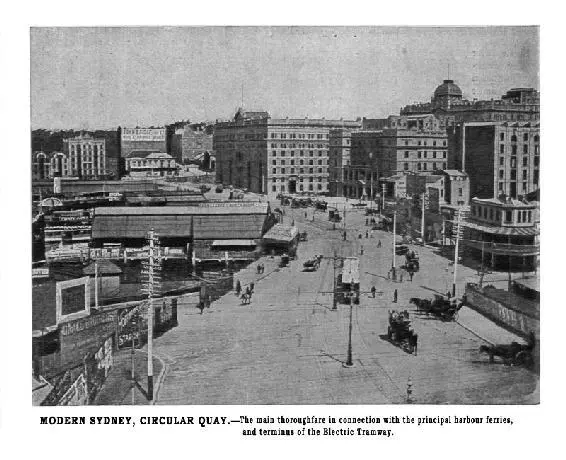

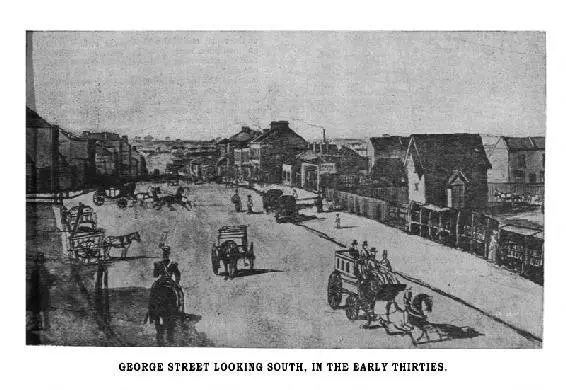

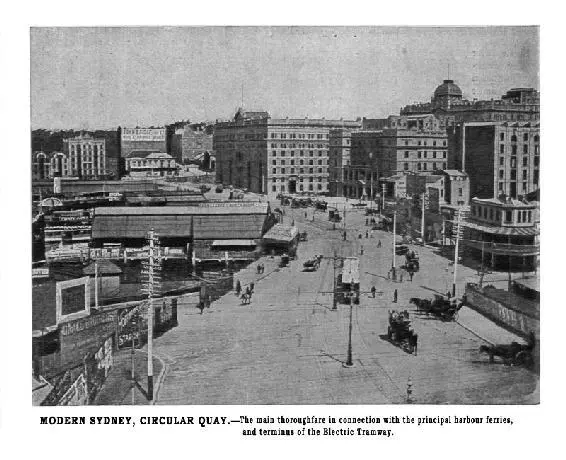

WRITING of Sydney in about 1821-2, a visitor remarks: “This town covers a considerable extent of ground, and would, at first sight, induce the belief of a much greater population than it actually contains. This is attributable to two circumstances—the largeness of the leases, which, in most instances, possess sufficient space for a garden; and the smallness of the houses erected on them, which, in general, do not exceed one story. From these two causes it happens that the town does not contain above seven thousand souls. There are in the whole upwards of a thousand houses; and although they are, for the most part, small, and of mean appearance, there are many public buildings, as well as houses of individuals, that would not disgrace this great metropolis (London). Of the former class, the General Hospital and the Barracks are, perhaps, the most conspicuous; of the latter are the houses of Messrs. Lord, Riley, Howe, Underwood, and Nichols. Land in this town,” the writer goes on to say, “is in many places worth £1000 per acre, and is daily increasing in value, rents are, in consequence, exorbitantly high. It is very far from being a commodious house that can be had for a hundred a year unfurnished.”

He visited the market, already described, and was rather pleased with it, finding it well supplied with grain, vegetables, poultry, butter, eggs and fruit. It was held on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays.

The Bank of New South Wales, he thinks, “promises to be of great and permanent benefit to the colony in general.” Its capital at that time was £20,000, divided into two hundred shares, and its paper was now the circulating medium of the colony.

Education was spreading, and the schoolmaster was going, comparatively, far afield. “There are in this town,” says a historian of these early twenties, “and other parts of the colony, several good private seminaries for the board and education of the children of opulent parents. The best is in the district of Castlereagh, which is about forty miles distant, and is kept by the clergyman of that district, the Rev. Henry Fulton, a person peculiarly qualified both from his character and acquirements for conducting so responsible and important an undertaking. The boys in this seminary receive a regular classical education, and the terms are as reasonable as those of similar establishments in this country” (England).

Compare this “seminary” business with the first school, already mentioned, of the Rev. Mr. Johnson, and it will be acknowledged that we were making rapid advances indeed. Here, bearing on the same subject, is an extract from the “Sydney Gazette” of the day:—

“Sydney Academy, No. 93, Phillip-street.—Wanted a Drawing and a Dancing master; persons properly qualified, and who can give satisfactory testimonials as to character and abilities, will meet with liberal encouragement by applying as above. Likewise, wanted a good laundress.”

And also: “Boarding and day-school for young ladies by Mrs. Hickey, Bent-street Sydney; opened for a limited number, where they will be instructed in English Grammar, writing, geography, and the French language. Terms: Under ten years, board and tuition, including English grammar and plain work, per annum £20.”

Then, for the opposite sex: “To parents, guardians etc.—Mr. Cuffe begs leave respectfully to acquaint his friends and the public that he has removed his day and evening schools from his late residence in Pitt-street to Macquarie-street where every attention is paid to the education of youth in all its branches, by himself, and able assistants, terms as usual. N.B.—A Sunday-school will be spiritually and morally attended to.”

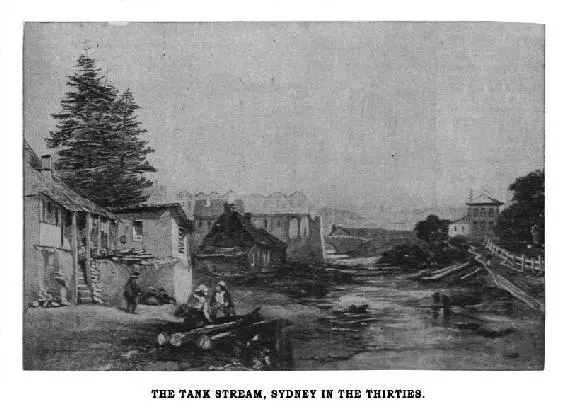

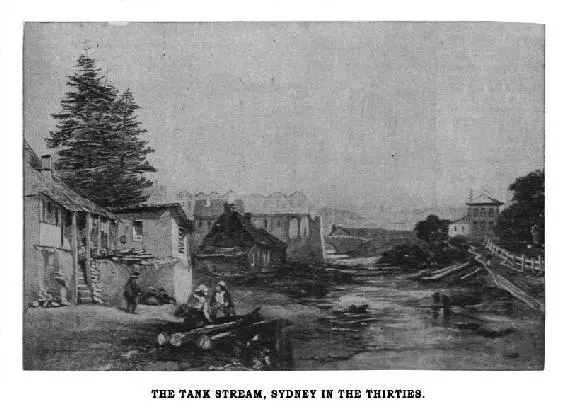

All this sounds very fine; but it must be kept in mind that the city proper was as yet scarcely more than a collection of huts, with, dotted amongst them, the comparatively huge buildings of Macquarie’s regime: that the waters of the Cove still washed up to where the Paragon Hotel now stands, and that the gallows, upon which men were hung in batches, was a prominent feature of the city.

The first place of execution, by the way, was, as nearly as can be gathered, near Hyde Park, not far from where St. James’s Church now stands. But, although accounts differ in this matter, it seems pretty certain that the site of the original gallows afterwards formed part of a garden, taking in the ground upon which is erected the Supreme Court; and, probably, this garden ran up to the corner of our King street. However, this may be, the gallows, in 1804, began a series of journeys; close to the corner of Park and Castlereagh streets, occupied in 1848, as it is now, by the Barley Mow Hotel; thence it was taken to some part of Sussex-street, where, in the same year, stood Barker’s Mills: then it was moved to a piece of ground near Strawberry Hills; then to the back of the Military Barracks; from there, in the beginning of the twenties, this much-travelled machine found a resting place on the summit of a cliff in Princes-street, at the rear of the gaol in Lower George-street. Its final journey was to the front of the new gaol at Darlinghurst, where it performed its first duty on two men convicted of murder, in October, 1841.

Innumerable arguments have taken place about this matter of the precise situation of the original gibbet. But by what can be learnt from careful research, the above is as nearly as possible its early history.

A dominating feature of the Sydney landscape, to which reference has already been made, was the windmills crowning some of the most prominent heights, and forming, as will be seen in the old prints, a not unpicturesque element in the scene.

Steam, for the purpose of grinding com, was not utilised until about 1828. Says the “Gazette” of 1819: “Mr. John Blaxland begs leave to inform the public that he has erected a mill for the grinding of grain, the stones of which are the production of the colony; and that he will grind wheat at 1s per bushel. Any person found taking stones from his Luddenham Estate will be prosecuted.”

The last intimation shows that the editor of the “Gazette” had to suffer imposition as well as his modern prototypes, it being, to all intents and purposes, a separate advertisement. But, then, Mr. Blaxland was a person of weight in the community, whilst the poor newspaper man of those days had to tramp round the country for many miles, and in all weathers, humbly soliciting payment of two, and even three, years’ overdue subscriptions.

Читать дальше