“We understand,” says the report, “from Mr. Hogan that there had been a conspiracy to take the ship from him. This was, however, happily defeated. Nevertheless, the commander felt it his duty to punish many of the ringleaders very severely; in fact, when they arrived in Sydney they were carried from the ship to the hospital.” That is all. But reading between the lines one can imagine unpleasant things.

Emboldened, perhaps, by the cruise of the Experiment, a sister snow, the Susan, presently arrived—231 days from Rhode Island. She took her time, and touched nowhere. She was laden with spirits, broadcloth, and a variety of useful articles. A desperately long and lonely journey for a small vessel of, likely enough, not 300 tons.

One vessel, the Britannia in these years—1794-1798—is constantly mentioned as bringing stores and live stock to the infant colony from Calcutta, Madras, and Capetown. Perhaps she may be looked upon as entitled to the distinction of the first “regular trader” to Sydney.

Of course we had nothing much to export, as yet. Nor was our first shipment, when we did imagine we had found something worth sending away, much of a success. Somebody, it appears, had made a big lot of grindstones out of the coarser sort of freestone. These were sent to the Isle of France, and deposited there with an agent for disposal. But one morning a slave, rushing into his master’s room, exclaimed, “Massa, massa, oh my gad, grindstone all run away!” It had rained in tropical fashion during the night, and demolished the stack of Australian grindstones, floating some of them out of the yard, and about the streets, and washing the more porous ones into mere sand. This story is, however, probably apocryphal.

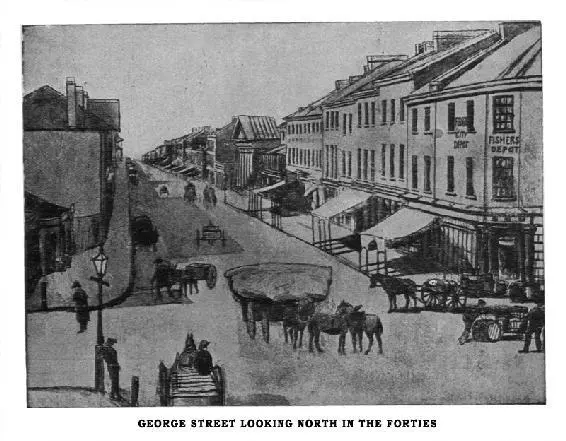

But although these sporadic exits and entrances of wandering ships made Sydney, even in those far-off days, a port, journalistic recognition of the fact did not come until the printing of the first newspaper, in 1803. In it—

“Notice is hereby given that the ship Castle of Good Hope will positively sail for India on Sunday, the 13th current; and Captain M’Askell requests that all claims may be given in to him by the 10th.”

Then again, the editor, to make the most of his one ship, expatiates as follows:—

“The Castle of Good Hope is the largest ship that has ever entered this port, and measures about 1000 tons. During the passage she lost twelve cows and one horse, fell in with no other vessel, and met with no accident. Her passing through Bass’s Straits instead of going round Van Dieman’s Land considerably shortened her passage, and saved many cows.”

In a day or two, however, the paper is enabled to chronicle the arrival of a “whaler, the Greenwich, with 1700 tons of spermaceti oil, procured mostly off the north-east coast of New Zealand.”

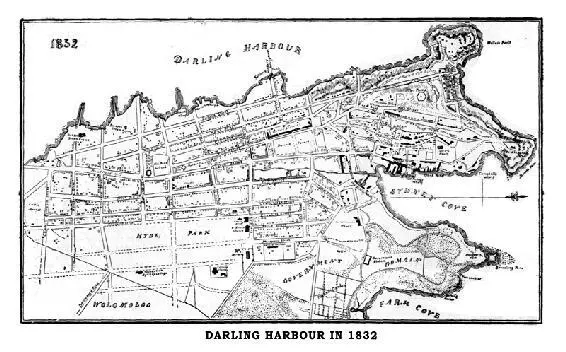

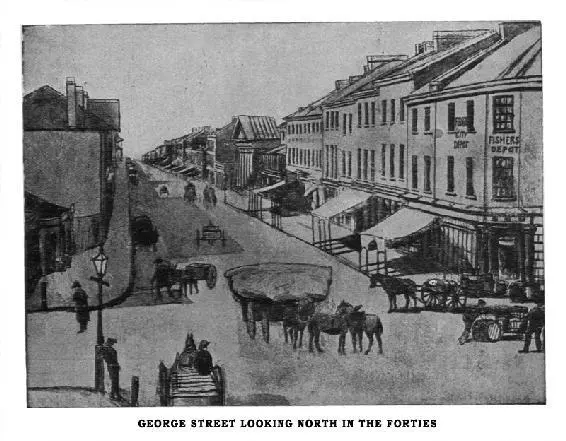

And ever as the months pass, so does “ship news” require more space for both deep-sea and coasting—the last under the title “Boats.” “Came in from the Hawkesbury on Saturday last, the 19th instant, the William and Mary, W. Miller, owner, laden with wheat,” and so on, and so on. Deep-sea ships lay at anchor in the Cove, the small fry came up to the “Sydney Wharf.” “On Sunday morning last came five boats from Kissing Point with fruit, poultry, vegetables, and potatoes.”

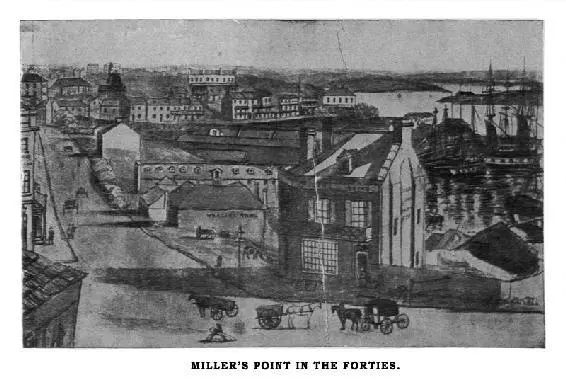

Whalers seem to have put in pretty regularly to refit and re-victual; heaving down on some soft spot on the shores of the Cove for caulking of seams and patching of copper after the long cruise. In the thirties, whaling became a very flourishing industry indeed, attracting many men and ships from England and Scotland. But we shall have occasion to glance now and again at the state of the port during the progress of this chronicle.

On February 15, 1811, the second year of the reign of Macquarie, was born the first Australian by an Australian mother. His name was Arthur Devlin, his birthplace Liverpool, on the banks of George’s River in the County of Cumberland, New South Wales. His subsequent career is of interest from his having been one of the first whaleboat’s crew which claimed the championship of the colony. His companions were James and George Chapman, William Howard, Andrew Melville, and George Mulhall. The first race took place in 1830, and was from Dawes’ Battery round Shark Island, and back to the starting place. At that time the port was full of whalers, and competition was therefore keen. But these six young Australians, all standing over six feet, were too much for any of the other boats, and won easily.

Early in 1895 a contractor working on a piece of vacant ground in North Sydney, used as a market garden twenty years ago, unearthed three tombstones. And to these stones hangs a story that is part of the story of our city, and must be here briefly told.

The inscriptions, then, on these tombstones commemorated the deaths of the surgeon, the chief officer, and the master of the ship Surrey, all of whom died on the ship’s first passage to Sydney—a very terrible one, indeed. Early in the month of July, 1814, the ship Brexhornebury, while off Shoalhaven, fell in with a big vessel lying-to, her sails in confusion, and signals of distress flying. She proved to be the Surrey, transport, from Spithead, with 200 male and 139 female convicts on board. There was also a detachment of 25 soldiers. Contagious fever had broken out on board, not only among the convicts, but also among the officers and crew. The captain informed the master of the Brexhornebury that 28 of the male convicts, two soldiers, the chief officer, and two seamen had died; that he and the remainder of his officers and crew were still suffering; and he implored help to take his fever-stricken ship into Port Jackson.

Naturally there was no disposition to eagerly board the Surrey, and the boat’s crew lay on their oars, and doubtfully surveyed the floating pesthouse and the scared and disease-marked faces that peered wistfully over her bulwarks.

At length a man, turning to the captain of the Brexhornebury, said, “I can navigate. I’ll go on board and take her in.” This unknown hero did so, and brought the Surrey to Sydney with her captain, Paterson, dying, and the other officer little better. Most unfortunately, there is no mention of that man’s name. It was worthy of mention.

The Surrey got into port on July 27, and was anchored in a convenient position “near the North Shore.” But not until April 31 was the camp, in which her people had lived in tents, broken up, and the ship brought round to the Cove.

This old “Surrey” or, as the early records call her, the “Surry,” was one of the oldest traders, or, rather, transports, to Sydney, making between 1814 and 1840, no less than eighteen voyages; and she must have been almost identified with and looked upon by the citizens as part of their history. The tombstones, it may be mentioned did not distinguish the site of the burial, but were merely memorials placed there by sorrowing friends and shipmates at a much later period.

Of interest, as showing at what an early age men in those days reached positions of sea-responsibility, it is recorded that Captain Paterson and Surgeon Brooks were only 24 years old; while Chief Officer Crawford was but 28. Where the last resting places of the captain and the surgeon were really situated there seems no evidence. The chief officer was probably buried at sea.

Читать дальше