Truly a terrible indictment this to draw up against any people! And though it was, probably, in great measure true, there is all the more credit due to our ancestors for having survived such a state of things, and made us what we are.

Nor must it be imagined that, for all the pessimistic declaration just quoted, the lieges were entirely without their pleasures and recreations. There was, for instance, racing in Hyde Park, lasting three days, and conducted after the Newmarket fashion, followed by an ordinary and two balls. The principal prize was a “Lady’s Cup,” presented to the winner by Mrs. Macquarie. “The subscribers’ ball,” says “The New South Wales Gazette,” “took place on Tuesday and Thursday night, and was honored by the presence of his Excellency the Governor and his lady, his honor the Lieutenant-Governor and his lady, the Judge Advocate and lady, the magistrates and other officers, civil and military, and all the beauty and fashion of the colony… A supper followed the ball… After the cloth was removed the rosy deity asserted his pre-eminence, and with the zealous aid of Momus and Apollo, chased pale Cynthia down into the Western World; the blazing orb of day announced his near approach, and the God of the chariot reluctantly forsook his company. Bacchus dropped his head; Momus could no longer animate.” All of which, put in modern phrase, means simply a very wet night indeed, and no one with much less than three bottles under his belt at daylight.

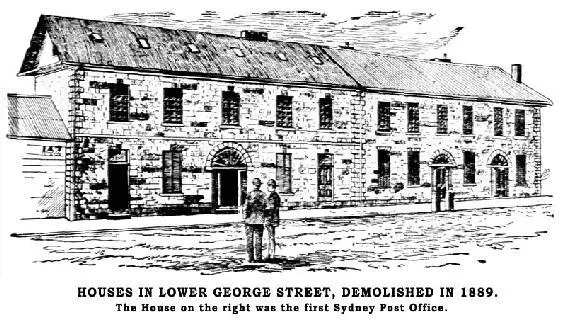

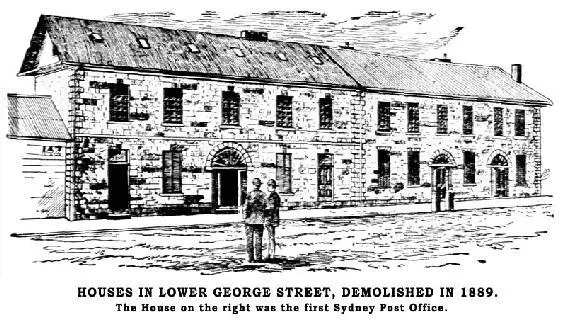

In the earlier days of the colony Divine service was performed in the open air, soon after sunrise, and under the most shady trees procurable. In 1793, a temporary church had been built at the back of the huts on the eastern side of the Cove, near the corner of what are now Hunter and Castlereagh streets. It was erected at the sole expense of the Rev. Mr. Johnson, already mentioned, of strong posts, wattles, and plaster, and thus enjoyed the distinction of being the first Christian Church in Australasia. In 1798 it was burnt down. Then the brick store built in the premier year of the colony was utilised as a church. The same store, which appears to have been the very first house in the colony worthy of the name, stood a little behind the site of the present Bank of Australasia.

The first part of old St. Phillips’ (since replaced by the present fine Gothic structure) to be built was the clock-tower. This was finished in 1797; but in 1806 it fell down. Formerly of brick, it was rebuilt of stone the same year. The church itself was begun in 1800; but not until nine years later did the Rev. W. Cooper officiate therein for the first time. It was finished about a year afterwards, and a handsome altar service of solid silver was presented to it by his Majesty King George III. St. Phillip’s was consecrated by the Rev. Samuel Marsden, a gentleman of varied attainments and pursuits. On the last Sunday in December, 1809, Lachlan Macquarie, not long landed, attended service at the new church.

Marsden, of whom the early chronicles have much to say, was, in addition to a clergyman, a magistrate, landowner, and stockbreeder. Thus in the very next number of the “Gazette” to the one announcing the consecration of St. Phillip’s, appears his name in conjunction with two other settlers, offering a reward of £1 sterling, or a gallon of spirits, for all skins of native dogs.

And now, 90 years later, we are still offering from £1 to £5 for dingo scalps!

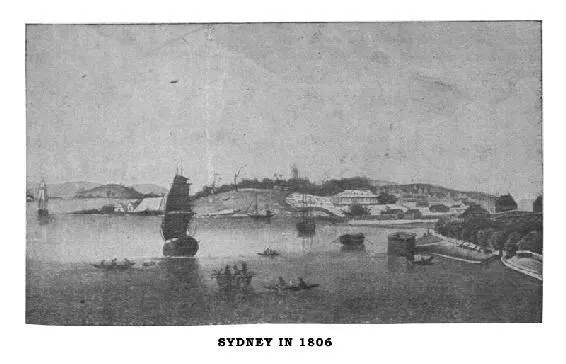

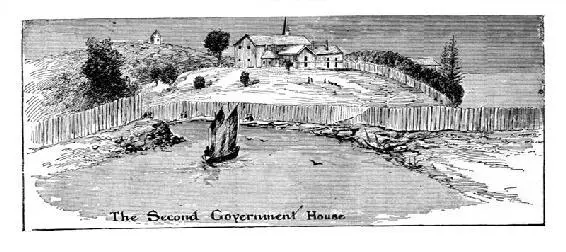

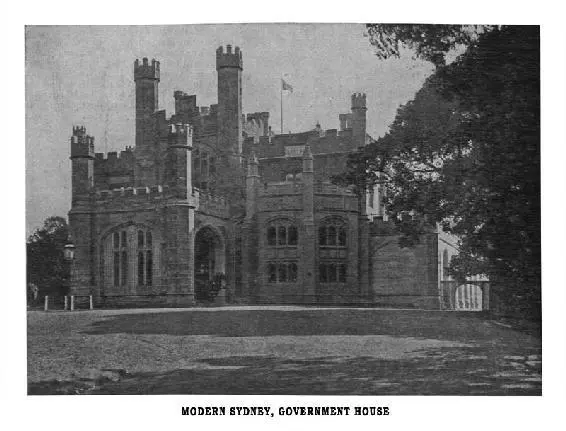

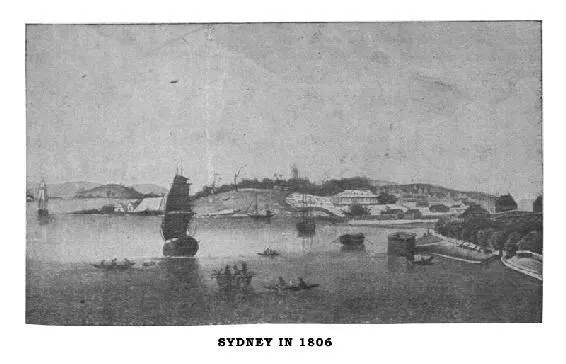

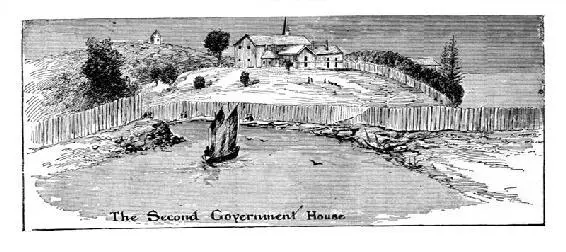

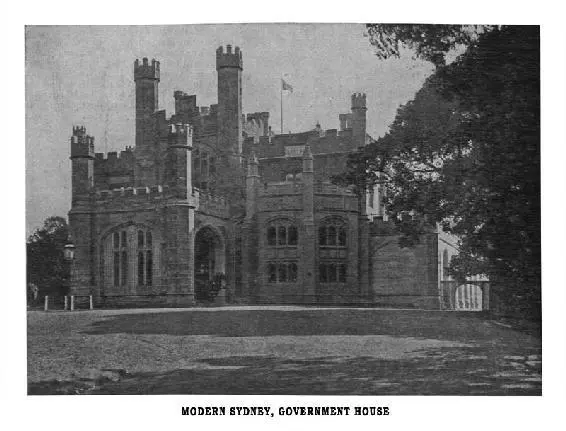

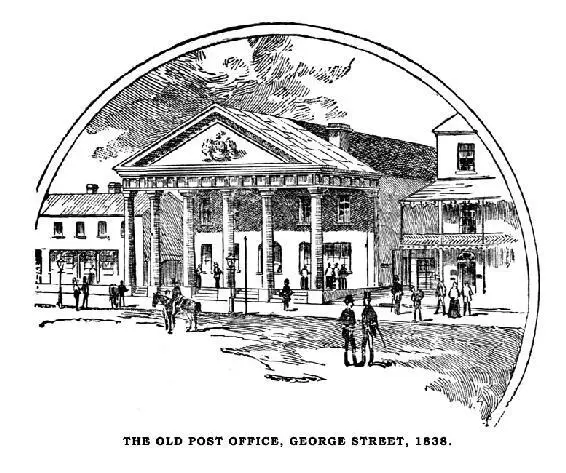

With the advent of Macquarie, Sydney began to shufle off something of the squalor and dinginess of those earlier days at which we have glanced. We have seen Phillip living in his four-roomed tent; then, later, in the hut dignified by the name of “Government House,” and surrounded by tenements, to which even it was a palace; we have seen the little settlement born in much travail to the accompaniments of hunger and hardships of every description, and the clanking of chains; the miseries alike of bond and free throughout the desperate struggle for existence during years that might well have depressed the stoutest hearts, dismayed the most sanguine souls. Then came the twelve years of Macquarie’s blended rule of despotism and benevolence; clear views and narrow, stubborn ones. You have read his first dispatch sent home when the first appalling impression of Sydney and its surroundings were hot upon him. Now read what posterity has to say of him:—

“He found New South Wales a gaol, and he left it a colony; he found Sydney a village, and he left it a city; he found a population of idle prisoners, paupers, and paid officials, and he left a large, free community, thriving in the produce of flocks and the labour of convicts.”

To Macquarie’s work as a builder there will be much occasion to refer.

Chapter III – The Harbor—Macquarie's Buildings

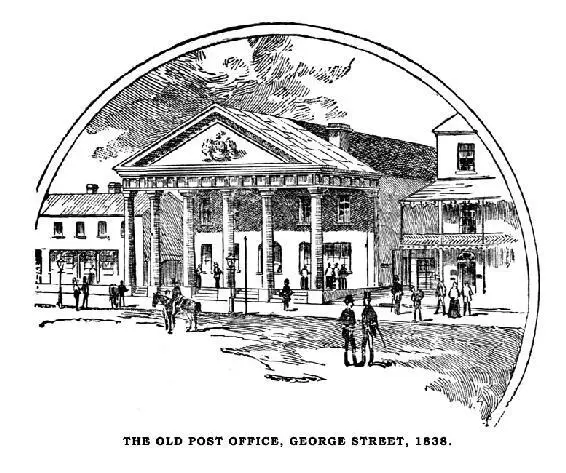

FINE a harbour as Port Jackson was, the early days, as may be supposed saw few opportunities for the use of it as such. The comings and goings of ships were confined to those of a few transports with convicts, and of provision vessels at long intervals from England or the Cape. Later, trade was opened with the East Indies and with the United States.

Passages were of great length. For instance, one ship, the Ceres, took nearly six months to come out. A curious incident happened on the trip. Touching at Amsterdam Island she took off four men, two English and two French, who had apparently been marooned from a brig called the Emilia. For no less three years had these unfortunates lived in that desolate spot, subsisting mostly on seal flesh. About 1794 a little trade with India begins; for we read that “the snow Experiment, from Bengal, and the sloop Otto, from North America, anchored in the Cove”—the last named five months and three days out from Boston. Trust Jonathan to discover a chance for trade, no matter how distant the scene of operations! His notions, too, we may be very sure were welcome enough to the citizens, and his bargains profitable to himself.

As time passed, however, the duties of the signalman at South Head became less and less of a sinecure, and on occasions there was almost what might be called a rush of ships. Many of these oversea arrivals had curious stories to relate, some of the weather, others of their cargoes. Amongst the last Mr. Michael Hogan, who brought “the Marquis Cornwallis from Ireland, with 233 male and female convicts of that country,” seems to have had a very rough experience.

Читать дальше